‘Gimme that ole’ time automotion,

Gimme that ole’ time automotion….’

A diamond in the rough, or just rough? It takes background knowledge of the market as well as careful technical inspection of a potential restoration vehicle to tell which you’ve got. Don’t go for the first example of any car you find, even if it means missing a sale or making a long road trip twice. The restoration will take much longer than it would take to drive to China.

It’s odd how we like lapstrake wooden sailboats with creaking Manila lines slapping against gnarly masts, how we like ragwing biplanes with slow-growling radial engines, how we like coal-black, coal-fired locomotives chuffing smoke and roaring steam, and — more in our line here — how we like old cars from across a wide ocean and from a distant time. Cars with hand cranks and flathead, sidevalve engines; cars with radiators, headlights and fenders all proudly separate one from another; cars with split hoods that hinge up along each side; sports cars from the 1950’s, still fast on those skinny spoked wheels with the knockoff hubs.

Many a classic Mercedes-Benz fits those nostalgic tastes, and many people are happy to spend considerable time and money restoring one. Perhaps you’ve considered offering that kind of work at your shop or even restoring a classic for yourself now or for sale later. A safer way to get your feet wet in the restoration business is to focus first on restoring someone else’s prospective treasure, letting the customer bet the vehicle will be worth the money at completion. You won’t get rich restoring that first car, and you might decide never to do another. Or you might find you like the work a lot and expand your restoration services into new areas nobody else has.

There are several advantages to choosing a Benz for the work: First, the company is still around, so information and parts are much easier to come by than if you set out to revive, say, a Stutz Bearcat, a Harmon V-16 or a Studebaker. Second, while nobody can predict how much a restored vehicle will be worth when you’re done, historically classic Benzes have held their value, just as modern Benzes do. Third (though this is a deep secret just between us, so don’t blab it around), Mercedes-Benz’ mechanic-friendly design means the cars are easier to work on than many other makes.

Mercedes-Benz has a classic restoration service, itself. Right now they’re doing restorations only in Fellbach, a small town near the factory at Untertuerkheim in Germany. Presumably most of the output from the Fellbach workshop will go into the Daimler-Benz Museum on the factory grounds and to other company displays, but they expect to do other work, perhaps including some private work, as well. They’ll probably open a second restoration shop in California in the medium future. Official Mercedes-Benz factory restoration shops will probably restore only a very few vehicles. However, not many carmakers can claim their factory can still put a fifty-year-old car in showroom condition using factory parts, factory tools and factory personnel. Mercedes-Benz can. It’s not likely, of course, the streets will be choked with their restorations, even in Fellbach.

There’s more involved in restoration work than you might suppose, I discovered visiting and conversing with independent shops focusing on Mercedes-Benz classics. Â Â I talked with Dave Polson of Autowerkes in Broadview Heights, Ohio; with Pieter van Rossum of Silver Star Restorations in Topton, North Carolina; and with Scott Grundfor of Scott Grundfor Co. in Arroyo Grande, California.

All of our independent restoration informants were at some pains to emphasize their opinions are their own. They use OEM information and parts when possible and available but improvise within their experience and knowledge of the factory’s traditions for cars earlier than 1947 for which information and parts are more limited or unavailable. Here are a few things to keep in mind if you’re considering expanding your own shop’s specialties to include restoration projects.

What is a ‘Restoration’?

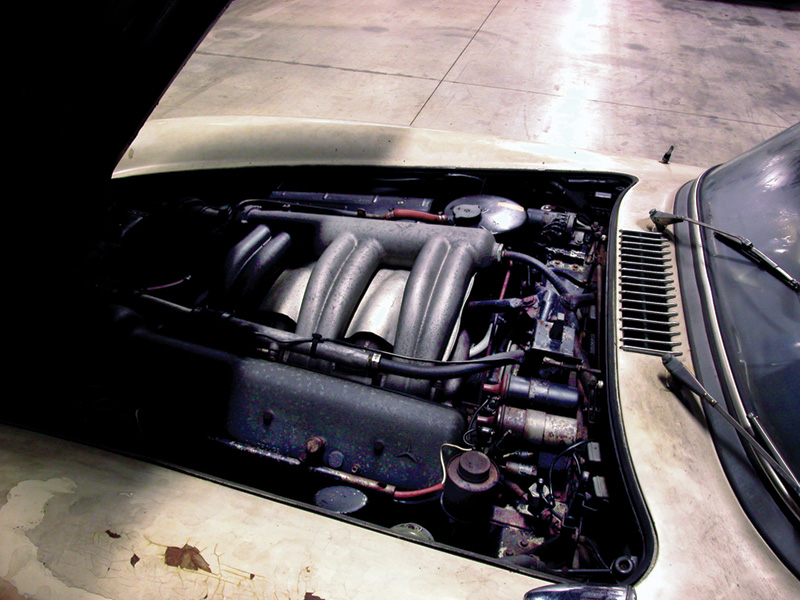

It’s radiator star may tilt, but this early 1970’s SEL was once the top of the Mercedes-Benz line. Not only did it sport hydropneumatic suspension and many other advanced technical features, with its high-revving 6.3-liter V8 engine (see below), it could leave any ‘Vette of the time in the dust, even with six passengers aboard. Most parts are still available for this car, should someone restore it.

Sometimes people just want a running example of a classic — not showroom-perfect, merely something to put-put down Main Street in Fourth of July parades, to chug along at old car shows or to tool around town on beautiful summer days when everyone else is gone so the roads are empty. But they want the real McCoy, not an ‘exotic’ plastic replicar bolted atop some more mundane running gear. Other people want to go all out for one of the major restoration competitions, like the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. They want to restore a rare car to showroom condition or better, but all original.

Preparing a car for occasional hobby use and less-than-perfectly-original restoration can be much easier and can even result in a better, safer vehicle. Nobody would use electrical wires with the old woven fabric insulation for any reason other than historic accuracy, not when you can get good, high-impedance, color-coded, plastic-insulated wires for much less than nostalgia-tech conductors. Even though the wiring system on an old car may be simpler than what you have in your kitchen toaster today, an antique automotive wiring harness does carry enough current to blow fuses or start fires. Similarly, nobody would use ancient fuel lines when safer modern tubing is available, and far more reasonably. But if the restored car is to compete for factory-condition, you’ll have to go with the horse-and-buggy-era materials. That is, after all, what the competitions are for. If someone wants the restoration for occasional driving around, however, you can use better supplies. Many classic cars have been converted to 12-volt systems just for the simplification that brings to everything electrical (you can use readily available batteries, lamps and an alternator, for example). Concours d’Elegance traditionalists will say ‘tut-tut,’ but that’s what traditionalists say, anyway.

There are two large worlds between these extremes, one world of time and another world of money. The different levels of vehicle restoration range from merely pounding out the dents and getting the engine running (which we won’t consider here), to making from an old car something that is much like it once was but with sensible modern compromise upgrades like a 12-volt electric system, or finally to fielding the winner at the Concours d’Elegance. Some cars could never reach that state of exalted elegance merely because of the cars they are and the times we live in. Restore a 240D Model 123 to flawless showroom condition, and you have a fine, useful, roadworthy car, old enough for antique plates in many states, but you don’t have a conveyance to wow the plutocratic swells at the country club. Good a car as it is, nobody with Roman numerals after his name dons his tweed driving cap, wraps on a monogrammed silk scarf and laces up his stringback ostrich-skin driving gloves to slide behind the wheel of a 123.

It takes about the same amount of work to restore one make of car as another of the same era, but certain automotive marques hold a resale value others do not. Guess which!

Dave Polson’s second piece of advice to a shop considering restoration work (right after ‘don’t do it — it’s too much work’) was, if it’s your money, find a convertible (or a “cabriolet” or a “roadster” — Mercedes-Benz uses the three terms for three distinct ways of putting the top down or taking it off) for any car you buy and restore yourself. Nothing else carries the same restoration demand or resale value. Pieter van Rossum agreed, “If the top comes down, the price goes up.” As a person of automotive technical savvy, you probably know that even the stiffest, girder-frame convertible will twist and flex and lift one squealing wheel or another off the ground in a braking turn, even though a torsionally stiffer coupe or sedan could handle the same curve with quiet, competent serenity. That doesn’t matter. If competitors had a completely free hand to use any kind of machine to blast around left-handed circles as fast as possible, the USAF could quite literally blow the doors off everything on the NASCAR circuit.

|

Our cover and center pages show what has to be the most spectacular car restoration ever. This 1911 Daimler Mercedes (not a Mercedes-Benz! The companies were many years from their merger when it was built) has a steam-bent mahogany strip body with ribs of ash, called a “skiff-body” because of its similarity to boat construction. The original was built on a Daimler chassis by Jean-Henri Labourette of Paris, and the car’s first owner was Henry Stetson — he of cowboy-hat fame. When the average American household income was $500, Stetson paid $18,000 for this car, the only one of its type. You’re looking at the profits from a lot of cowboy hats. The engine is a ten-liter (that’s 600 c.i.d.) four-cylinder with two exhaust and one intake valve per cylinder, arranged in sequential banks of two. The Daimler MotorenGesellschaft rated the engine at 90 hp at 1300 rpm. The car’s top speed is between 75 and 100 mph — you’ll understand that nobody is going to check on that. The car weighs a bit over two tons. StarTuned most sincerely thanks Scott Isquick, just the second owner of the car, for showing it to us and driving it under its own considerable power. Mr. Isquick is the patron who supported the restoration, and it is the jewel of his antique car collection, of course. The work was done over several years with 12,600 man-hours of highly skilled work. If we weren’t too slack-jawed with astonishment to manage it, we’d tip our editorial hat to the man who did the job and his associates, to Dale Adams. If he tells you anything that conflicts with anything we’ve written here, obviously he’s right. |

What counts in many restorations is The Look.  Neither utilitarian nor technically superior transportation is the story. Classic car fans are after the classic look and the classic sound — and seeing themselves framed in that classic look and sound.

Time and Money

Most people who want to restore a classic car expect it will be expensive, but they don’t know how expensive. But nobody knows how long it will take, either, and that may challenge people more. Restoration projects not only require patience and money from the customer, but patience, skill, storage space and time from the shop doing the work. If somebody has to have a classical car restored by a certain imminent date, let him do the work himself.

At the top restoration level, where our correspondents work, they’re largely in control of things. Want to have one of their shops restore your car? OK, they will. But on their terms. None of them can start earlier than nine months to a year from now. None of them will give you a completion date certain or an all-up price. They do say it takes at least 18 months to two years once work starts, maybe longer, and costs much more than you expect or they can estimate. They may accept a maximum price contract — after which work stops wherever the restoration stands. These are certainly not the arrangements we make for ordinary car service!

Not only is there no restoration flatrate book, there isn’t even a wild-guess, ballpark-estimate book. No two restoration jobs are similar enough to extrapolate one from the other, and the more experience someone has restoring classic cars the less likely he is to get specific about time or money. If you had two original cars in exactly identical condition and restored them to exactly identical condition, the price and completion date for each would nonetheless be different because the work time and parts prices would be different. Given the scarcity of cars worth restoring, there’s no way this can be otherwise.

Polson restored this beautiful silver 300 SL for a client who uses the car as his daily driver, at least in good weather. The ‘civilian’ 300 SL was very similar to the Gullwing, but Polson notes that few parts are actually interchangeable, even though their appearance is quite similar. The Gullwing is somewhat smaller and much more of an all-out racing machine than this car. It remains, nonetheless, a splendidly driveable machine, a fifty-year-old car that can probably outperform your modern car in every measurable test.

It’s understandable a potential customer might find this uncomfortable. You probably would, too. But don’t start out to restore a car until you work these issues out with your customer. A restored classic car is a hobby for someone relatively flush with money and time, but as Scott Grundfor explained, while some of his customers have been worth hundreds of millions of dollars, they — at least the ones he did business with — didn’t get that money by tossing it around. “Nobody ever told me, ‘cost is no object,'” Grundfor recalls. Likewise, many of these people are used to hard-bargaining business negotiations, probably much more used to it than you are.

Grundfor says the ability to deal with potential customers in a businesslike manner is as important for success in the restoration business as the actual restoration skills themselves. You can set monthly maximums or job totals; you can shoot and send photos at every step. But if there’s a fixed charge for the job and, as is certain, unexpected costs occur, either you have to take the hit for a problem you couldn’t have anticipated, or you shave expenditures somewhere else and produce an inferior restoration. Either way, one party or the other loses, probably both.

Make sure that everything is clear and in writing up front, perhaps even before the car shows up at your shop. Besides the clearest possible description of how the car should be restored, this should also include what happens should the customer decide during the restoration to halt the work or move the car to another shop. What happens to whatever money had been paid to that point, for instance? Who owns parts bought but not yet installed, parts ordered but not yet delivered? Parts delivered but not yet paid for? If you farmed out woodwork or upholstery, who pays your subcontractor to get the parts back?

Cash Flow/Keeping in Contact

Every piece of restoration work is a self-portrait of the worker (just as every photograph is, as you can see). To put a car back into the condition it was in the day it was built and to do it so well that your work sustains the closest scrutiny, that is a rare skill, indeed. Notice the superthin bead of weatherproofing around the mirror base. Dave Polson restored this car for a customer who uses it as a daily driver. Whether it had such detailed rustproofing when new, to make the car last indefinitely, such work is needed.

A regular billing cycle not only carries the advantage of regular income for the shop and regular communication with the customer; it also minimizes the cost at any point for the customer. It’s much easier for someone to pay $1000 a month for several years toward his restoration than the entire hit at the end. What’s more, if there is a problem or delay with payment, it’s only the last installment that is in dispute with the regular billing cycle method. If somebody wishes to haggle a price down, it’s only that last billing-cycle time-slice on the block. If the customer gets regular notice what work is going on and what it has cost, his chance to raise questions and objections comes then, not a year or so later when the car is done. Besides, if the customer is current with his bill, you won’t gnaw your fingernails quite so much if he shows up at the shop and wants to test drive the car (There have been cases when the customer didn’t come back with the car)

The reason to go through this worst-case-scenario is that same point about time and money — the project will take much more of both than you or your customer anticipate. Most people, kept apprised of how the work is going and what the current problems are, understand and cope. Some don’t. Your restoration contract has to anticipate those latter. There’s no reason you should take the hit for them; better to have it all sorted out in writing first. For a small shop, the risk is too great.

Small trim pieces, like taillight surrounds or the numbers on the trunk of this 300 SL may sometimes be the most difficult pieces to find, if they’re missing. When you do find them, you may be astonished at the asking price, so make the effort to find a car as complete as possible to begin with. Sometimes it’s easier to find whole cars than individual trim pieces!

But that’s not unreasonable. Nobody needs a restored car, and few shops can really do the work properly. It will take many more work hours to restore any car than it took to build it in the first place. That will be at least as true of a current Mercedes-Benz vehicle fifty years from now when someone sets out to restore it. A car factory is not only a location for precision work; it is also a place of the most serious time discipline, focused on the efficient production of vehicles. Nobody will ever be able to replicate that work in the same time without the factory’s mass-production equipment or without the factory’s long-skilled workforce. Nor can the restorers pound out a classic nearly as fast as the factory did back when they were on the assembly line. Compare instead how long it takes the factory to install, say, a water pump with how long it takes you to replace it in your shop. Now add all the complications of extreme rarity, parts-location problems, repairing dubious fixes over the intervening years and the need to restore everything else on the way in and on the way out. You can’t scrape off the old gasket in the time it took the factory to bolt the original to the block.

Interior and trim work is unlike most other automotive work, involving upholstery skills, woodworking, leather craftsmanship and an attention to detail unparalleled anywhere else on a car. This is one of those areas where you just have to invent your own skills, at whatever cost of time and effort it takes.

There’s no beating the clock when there’s no flatrate ‘clock’ to beat, just the real one on the wall. Put in eight hours at a restoration shop, and you’ve clocked eight billable hours, not more, not less. If that seems unproductive to you… well, tough. Do other work for a living. This kind of approach would drive the manager of a high-volume maintenance and repair shop nuts; it conflicts with everything he’s come to think of as businesslike.

But a businesslike approach is critical to restoration work; it’s just not the same business. Even though completion of a restoration is far from an everyday thing at even the busiest restoration shops, they keep a steady income stream by billing their customers regularly. One of our correspondents bills monthly, another weekly. Sometimes the only charge is for storage while waiting for parts or while waiting for someone who can start the project. Sometimes the charge is for international phone calls and translators, necessary to chase down that elusive rearview mirror or grille bar or to find out what colors a carpet came in.

Restoration work, according to each of the shops we spoke with, is very different from ordinary repair and maintenance work. If you’re used to a fast, ‘productive’ pace, quickly rolling cars in and out of workbays; if you work with hard and fast quotes, based on flatrate manuals and wholesale parts catalogs, factored against what you’ve calculated is the cashflow each workbay must generate every hour to cover a high overhead and generate the expected profit — well, you’re not going to be comfortable with restoration. If your notion of a productive worker is someone who can hammer cars in and out faster than anyone else in the shop, well again, you’re not going to be comfortable with the kind of artisan who can do restoration work.

It looks rough, but mostly because of the aborted amateur restoration begun before Dave Polson got the car. He notices rust on the underside in the predictable places, but all the parts are there! This one’s a keeper.

About the worst business approach to restoration is by analogy with a home contracting model: half up front, the other half when done. But these are entirely different kinds of enterprise. An experienced home contractor knows very accurately what he will pay carpenters, plumbers and electricians, and he knows how much work they can do in a day. He knows accurately what he will pay for 2×4’s, sheetrock and shingles, and he knows from the blueprints almost exactly how many boards and nails he’ll need for the job. Usually, all of his costs remain predictable and stable.

Restoration of a classic car shares none of these characteristics. There’s no way to tell what parts you’ll need until you’re a considerable way into the project, and there’s no way to guess what those parts you don’t know you’ll need are going to cost when it’s time to buy them. Or where you’ll get them. Worse still, the rarer the part, the higher and more volatile the price: Every time an original headlight bezel for a Gullwing is sold, the price for the next one goes up.

This can sometimes lead to problems with certain customers, especially the most successful in other businesses. Someone used to barking orders and getting quick results may decide to put several people on the trail of some part needed. Trim pieces are particularly hard to come up with because they’re not available new anymore. It is surprising that a small plastic or cast-metal dashboard ornament may cost more than a fender, but a skilled sheetmetal worker can make a new fender. Gearing up to mold new plastic pieces exactly as they were made 50 years ago can, paradoxically, be very expensive. Some of those parts were made by independent suppliers, small businesses that closed long ago, suppliers that left no records. Send a gang of people after those parts, however, and watch the prices soar and the counterfeits multiply. Anyone in the business who has a real one, seeing the demand suddenly rise, will just hoard it in anticipation of more rise still.

You can never make a promise about when a car will be done for just that reason. Polson goes further. When someone drops off a car for restoration at his shop, Dave makes sure they understand he not only can’t promise a completion date, he can’t promise a date he’ll start the project, either. He’s been doing this long enough and has a large enough number of good restorations in his record people just have to work with any reasonable conditions he sets, or he’ll work with different people. With all the projects underway, everyone has to understand that fixed schedules and deadlines don’t make sense here. It will take a long time to restore a car, certainly longer than the customer expects.

A car with a complete set of parts is worth much more than an otherwise good car with critical pieces missing. This 300 SL has everything that was there originally, even pads for the sun visors. Restoration work can begin right away, without waiting to spend hours or days on the phone, chasing pieces in faraway places.

No restoration is inexpensive. One thing you should certainly make clear to a potential restoration customer: For less money than a thorough, frame-up restoration will cost — probably for much less — he can get a new Mercedes-Benz with better performance, better fuel economy and higher reliability than any restoration, however well done. The designers and craftsmen who build Mercedes-Benz cars have worked for over 100 years not only to build the best cars they can, but also to constantly improve their product over time. They don’t ‘build ’em like they usta.’ They build ’em much better. Restore a classic car to better-than-new, it still can’t compare to a modern car as a useful vehicle. Even the most luxurious car built in, say, 1925 rides about like an old tractor, and your customer should know that up front. Perhaps not every automotive design change proved a good idea in the long run (tailfins withered away, after all!), but carmakers kept the ones that did and corrected the ones that didn’t. So a Benz of today really is dramatically better than one from 50 years ago, including such legends as the Gullwing (What could you do if the car flipped over in a race or sank in a lake, for instance? How could you open a door to get out?).

The 50 year-old engine is in good condition and will require little more than cleaning. Many cars restored to original condition will never drive another 1000 miles, so there is minimum need to overhaul the engine. Oil leaks, however, are a common problem, often from gaskets that have dried or cracked in place.

Many classics also require much higher driving skills, because they were built with square-cut, nonsynchronized gears (double-clutch up and down, every time!), hand-adjustable spark advance and fuel mixtures and the like. Automatic transmissions? Power steering? Power brakes? Heater? Defroster? Air conditioning? Seat belts? Crush zones? Roll bars? Collapsible steering columns? Ha!

Mercedes-Benz was the first carmaker to routinely employ experimental crash-testing as well as analytic examination of actual accidents, beginning in the early 1950’s. Over the decades, that knowledge has accumulated to quite an applied science, but on earlier cars, from the 1930’s and before, automotive safety is almost entirely a matter of driver skill and prudence. Some old cars require the driver to light the carbide headlamps with a match. Many use ‘suicide’ doors, hinged at the back, easier to get in and out, but very exciting if they come open underway. Some used tiny drum brakes, operated by lever and cables, working only on the rear axle. Lots have skinny tires with inner tubes, mounted on flexible wire-spoked wheels, with no more traction for steering or stopping than you’d suspect. Others with hand cranks not only require considerable strength of arm, they may be impossible to start for someone who is left-handed (Try it. You can crank much more easily clockwise than counterclockwise if you’re right-handed, and vice-versa if you’re a lefty. But there aren’t any counterclockwise-turning engines from the crank-start era!). And should the motorist forget to retard the spark lever, a backfiring crank can break bones. Your customer should know all of these kinds of things up front.

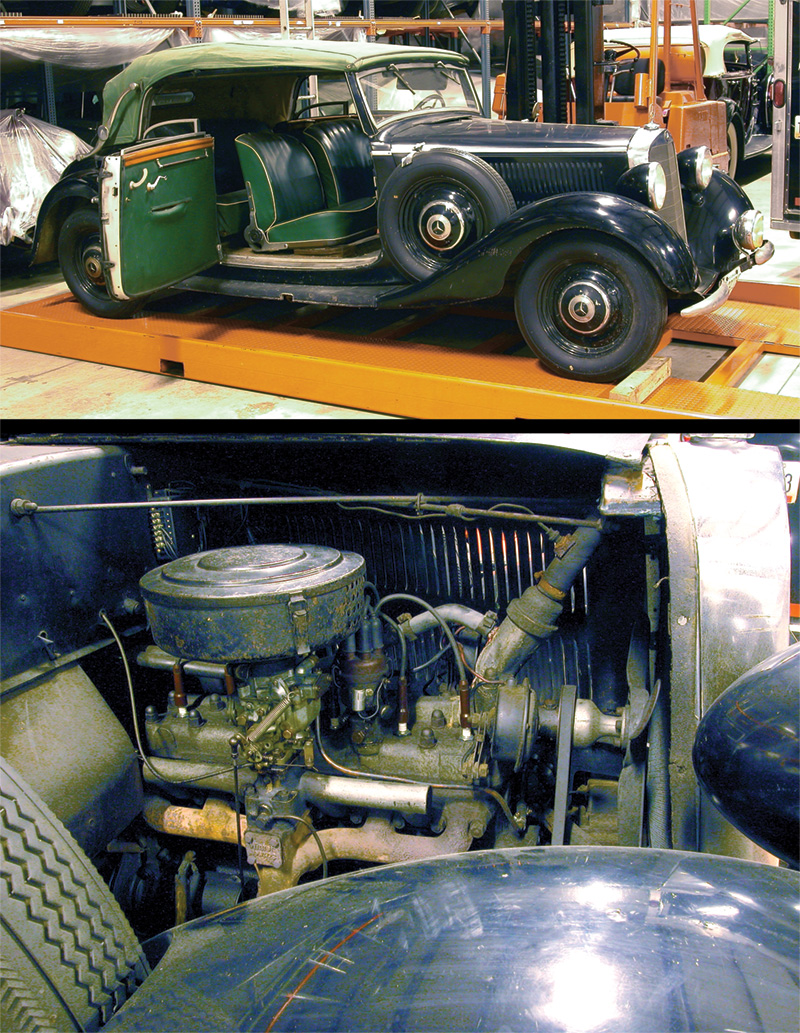

The six-cylinder 2.6-liter 1937 flathead engine was high-tech at the time, if not motorsport material. This 1937 260, restored to functional, not perfect condition is one of the few cars you’ve ever seen with functional Landau bars. Amazingly, it also has independent suspension on all four wheels, including a very ingenious and intricate four-spring geometry for the rear axle.

Doing the Work

Space, lots of space, much more space than you need even for a high-line body and paint shop is the first requirement for restoration. You’ll notice all three of the successful shops we listed at the beginning of this article are located in relatively remote areas, areas where nobody crowds them next door, areas where rents are low or you can raise your own building inexpensively. They’re relatively inconspicuous, too, since there’s no walk-in traffic to speak of, and you don’t want gawkers. Even though his shop sports a discreet heliport out back, Polson’s sign in front is not much larger than this magazine opened flat.

This is not a business for someone renting very expensive workspace in a downtown area. None of the three shops we talked to are in central cities; many of them have never even met most of their customers — the cars just show up in sealed car carriers after all the business arrangements are final and go back the same way. Have lots of room and no immediate demand for it, or move someplace where you can get it.

Next, Scott Grundfor mentioned that most people who can do restoration work are more like artists, often people with developed interests in music or fine arts, people who work on their own without an overseer, people who focus on the quality of their work first, last and always, not on the clock. If they need a special skill they don’t have, whether it’s leather upholstery or working with burled walnut veneer or noodling out a 1930’s magneto, they go out and learn that skill on their own. Pieter van Rossum said the couple of people who work at his shop just figure out how to do whatever comes along, whether they’ve done it before or not. When I visited Dave Polson’s shop, one item I couldn’t miss: a meticulously equipped enclosed trailer with innumerable ingenious devices, storage bins, winches and structural lifts — all beautifully hand-built by Greg Bickford, one of his artisans. Autowerkes has four or five such trailers and a spectacular tractor-trailer combination, all just to transport customers’ vehicles in safety. The implicit message was clear: Whatever they need, they can make.

At the same time, restoration work is hardly a relaxed kind of work. Very many problems are novel, and you have to solve them if you expect to finish the work. You have to be able to sustain hard work under conditions of uncertainty — sometimes your solution won’t work, and you’ll need to think of something else. This is not the easiest way to make a living.

Cherry-Picking

After you have the workspace and find some skilled associates, the next hard step in restoring a classic car is finding the right car to restore. Not to put too sharp an edge on it, the easiest car to restore is the one that requires the least restoration, the one with no damage and all of its parts. Obviously, the rarer a car is or the more insistent you are upon a specific model, the harder it will be to find a good, complete example to restore. You’re not going to find a ’55 Gullwing or a ’36 540K at the boneyard for cheap because the people there don’t know what it’s worth and have scheduled it for the crusher tomorrow. Most people with an old, restorable car on their hands think it’s worth much more than it really is.

Get a car with a complete set of parts if at all possible. Otherwise, Murphy’s Law insures several critical missing parts will be unobtainable. While the factory can still make a surprising number of parts for older Mercedes-Benz vehicles, it’s not as though they have a roomful of doors for SSK’s in various colors, just waiting for orders. They can build or cast or machine all sorts of things, but not on a moment’s notice, and they don’t work cheap. If possible, hold out for the best example you can find — it’s easier to keep looking for a better example for a while than to search for missing parts later or fabricate them yourself. Getting a clapped-out beater as a parts car is dubious: Chances are the same parts you’ll need have already been stripped off the donor, fallen off or rusted away, or worn out. Genuinely rare cars, of course may be another story: If your customer wants a 1911 Daimler-Mercedes skiff-body, he’ll have to talk to Scott Isquick, who has the one and only.

A partially restored car can be even more of a problem. Each of our informants has horror stories about botched and aborted restorations that were more trouble to fix than a straight fixup job would have been.

Don’t store any vehicle over a dirt floor. It can hold prodigious amounts of moisture, which percolates up and rusts out the car in all the most vulnerable places. A vehicle stored over a dirt floor may not be restorable for that reason. Barns are not garages.

Rust is a very difficult problem because it’s often hard to tell when to remove the rust and when to replace the metal. Often the most serious rust damage is deep inside, invisible without very careful inspection, including dismantling. Most cars, you already know, rust out rather than wear out. The more valuable the car is and the less it is used for everyday transportation, the more likely this is to happen, a major problem for museums and other automotive historic centers. This is, in fact, a major problem even for cars that have already been restored. Somebody parks them in a garage or a museum, and they sit and rust or seize in place internally. Then a few years later, even with fresh fuel and a new battery, they can’t start and need extensive repair.

A surprising aspect of restoration, however, and strikingly at odds with ordinary work, is the comparative unimportance of restoring the engine. But after all, a car that only drives a few hundred miles a year is not going to wear out an engine soon. This argues for finding one with an engine that needs little work, obviously.

While as we mentioned, you can get new fenders, hoods and other sheetmetal from the factory for many classic Mercedes-Benz cars, you’ll want to preserve what you can, both from a historical and economic perspective. But this is not like bashing out the day’s dents on Brooklyn cabs: You don’t yank a rear quarter roughly into place with a slide hammer and then slather over the zits and ripples in the steel with trowel-loads of bondo followed by paint from a spraycan. You learn, by practicing with scrap, to make a butt-to-butt joint with no bulge or visible seam; you learn to duplicate whatever compound curvature the piece had with a Yoder hammer or on an English wheel you learn the same skills those master German machinists had so long ago.

When inspecting a prospective car for restoration, pay attention only to the condition of the car, not to its purported history. Maybe once upon a time it did belong to Greta Garbo or Al Capone, maybe not. That won’t affect your restoration work. Leave all that for your customer to collect from official vehicle records, both the factory and licensing bureaus. Similarly, with a car that’s 50 or more years old, it makes no difference whether it’s from Florida, Texas or California — it probably didn’t spend all the intervening time there. Any car that old will have been maintained and serviced by a variety of people in a variety of ways, not all of them optimal.

Digipix Records

Digipix Records

The general structure of a restoration is straightforward: Take the car carefully apart, keeping track of where everything fits and what needs replaced. If you’re working on more than one car at a time or if the car will be in your shop a long time waiting for parts, shoot photos to remind yourself where things were when you started. With an old car they may not be in the right places, but at least you’ll know where everything was when the car rolled in the door.

Grundfor mentioned also the importance of keeping the work organized. A typical classic car worth restoring has about 30,000 parts, virtually all of which you’ll remove at least for inspection and cleaning in the course of the work. If you just pile these parts in whichever corner looks least crowded at the moment, will you be able to get everything back where it belongs 18 months or two years later, when you’re reassembling the vehicle for the final time? And what if you have several restorations going at the same time? ‘Where on earth did this odd-shaped blackmetal shoulder bolt with the reverse thread come from?’ Will you remember?

The best way to do this is with a digital camera because you have the photo record immediately. If one shot doesn’t work, change the settings and shoot again. Digital photos for a specific car can all be stored in the same folder on your computer or burned onto a car-specific CD. Clarity is what counts. You’re after a rebuild record, not art; the art will come from your hands and eyes, through your tools to the finished car. You don’t need the best camera or the best lens to shoot such photos, but you will find a tripod —even the cheapest tripod — makes more difference in the clarity of your photo records than anything else does. If possible, use as much light as you can conveniently get around the car. Many lights will yield false colors, either on film or on a digital camera, but you’re really not after perfect color replication — you want to know exactly where which part was to begin with. Use your camera’s timer and your tripod, and the photos will, whatever else, be usable to put things back where they were.

Knowing where the parts came from is only half the organization, obviously. Get a set of bins to keep the pieces you remove in some sort of order. You don’t want to have to look through everything loose in the shop to find that odd shoulder bolt in the digiphoto.

Final Touches…

Scott Grundfor emphasized paint and surface quality. This is not, of course, a particularly accurate way to duplicate the original finish, since modern paints are much better than those earlier. They come in more colors, too, so if a customer wants a perfectly accurate restoration, you’ll have to do some research to find out what colors were originally offered. Classic Mercedes-Benzes came in more colors than Henry Ford’s ‘whatever you want as long as it’s black,’ but not in every color available today. Of course, if your customer wants the car in Coast Guard rescue orange, you can do it; but that’s his vanity, not restoration.

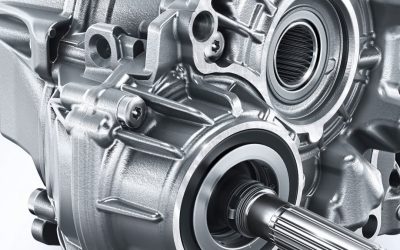

Classic cars were almost entirely handmade, and this adds to their value because of the skills of the workers who built them. It’s actually an advantage, when working with older cars, that they were built mostly by hand. That required a high level of work on the part of the manufacturer, but you can duplicate that quality of handwork if you’re careful and painstaking. It may not be as perfectly consistent as a laser-guided welding robot, but the carmakers didn’t use that technology to build the cars you’ll be restoring in the first place. But this is a hopeful factor for restorers because these are all skills you either already have — welding, painting, metalforming — or can learn on your own. What will happen when cars from the early 1980’s, the first cars with microprocessors and PROM’s, start to appear as restored classics is anybody’s guess. At this point, nobody can provide or build replacements for those control units if they prove needed, and given their sensitivity to small static discharges, moisture and other environmental assaults, they will. But that’s a problem for restorers in the future. Maybe they’ll develop the capacity to fabricate microcontrol units of their own design.

Canning the Preserves

There’s a continuing last step in classical vehicle restoration: Often such a car is not really suited for general driving, so you have to either pickle it for the ages or explain in great detail to the owner how to preserve it between his annual parade excursions. You don’t just fire the thing up and drive a few hundred yards around a display: That will leave the engine’s internal surfaces as well as the inside of the exhaust system covered with water vapor, condensed out of the fuel burned. Run a restored classic up to operating temperature and hold it there long enough to blow out all the water you make — run it until the inside of the tailpipe is completely dry. Do this every time you start the engine. That’s a good rule with any car, but with one that may not be started again for a year, it’s standard procedure, a necessity.

Other preservative measures are well known: Use gas stabilizer; trickle-charge the battery from time to time; keep the tires pumped up and fix any that develop leaks (no occasional task with cars using old-style, inner-tube tires); pull the plugs and spray oil into the cylinders to prevent internal rust; bag the car to prevent dust accumulation and put an oil pan under it (those old rope, horsehair and leather seals don’t work any better now than they did back then). Some people set a restored car up on jackstands to preserve the springs, which may be hard to replace if they sag. Irreplaceable springs can sometimes be stretched and heat-treated/oil-quenched to their original tension. Vintage tires (or usually better, vintage-looking tires that are really modern tires in ancient disguise) often need covered if they are to last in storage. Tires for antiques are expensive, but as little as the cars are driven, they may well be a one-time expense.

Mercedes-Benz may be the only carmaker to regularly include instructions for layup and storage in most of their shop manuals. While these procedures are similar for all cars, check those for the vehicle you’ve restored for its particulars. Largely complete technical information is available directly from the manufacturer for all Mercedes-Benz vehicles built since 1947. Owners clubs and restorers often have extensive knowledge of earlier models, even to maddening detail.

Genuinely classic cars are part of the historical technical treasure of humankind. Even if an early car is not, or is no longer by modern standards, a useful machine, it holds a place of importance in our technical history. An old car is just an obsolete machine; it has no rights. But we owe it to our grandparents — who built the cars — and to our grandchildren, maybe not yet born — to preserve enough of these machines that they can have a direct perception of what it was to be a person in past times.

Each of our sources has an Internet website, where you can learn more about his slant on Mercedes-Benz restoration:

www.silverstarrestorations.com

and last but hardly least, www.mbusa.com

0 Comments