This small block Chevy uses a Vertex magneto to complete its vintage look. It would most likely perform better with a different distributor and carburetor package, but it wouldn’t look nearly as cool.

One of the best ways to get a big bang for the dollar spent when you are looking to increase the power of a carburetor-equipped engine is to tune the ignition advance. The mechanical spark advance curve that was used on most production engines when they left the factory was tailored to work reasonably well under a wide range of driving styles and operating conditions. As a result, a typical vintage engine came with very stiff centrifugal advance springs in its distributor that allowed maximum mechanical advance only when the engine was near red-line rpm. This means that if spark advance is properly tuned to match the needs of the engine at other speeds, you will increase both power and driveability without spending much money!

The ignition advance curves that factory engineers used when just about every car on the road had a carburetor were designed for a blend of gasoline that no longer exists. Modern unleaded gasoline burns faster than the old leaded type, but it is somewhat harder to ignite. Today’s fuel blends are designed to reduce the evaporative and exhaust emissions of a modern computer-controlled vehicle. The computer is continually adjusting the spark timing and the air/fuel mixture to match the needs of the engine. Since most pre-1980 carburetor-equipped engines do not have an on-board PCM (Powertrain Control Module) to make the continuous tuning adjustments that are needed for it to run its best with today’s reformulated gasoline, fine tuning the ignition timing (and the air/fuel mixture it gets from the carburetor) is the answer for better all-around performance.

To make an engine more efficient, the air/fuel charge in each of the cylinders should be ignited at exactly the correct time in the combustion cycle so that all the energy potential is converted into useful work. The ideal ignition timing for maximum power production is just after the point where detonation or pinging would occur. Correctly timed ignition will cause peak cylinder pressures at around 12- to 15-degrees after TDC (Top Dead Center). If peak pressure is reached too early, power will be lost as the piston fights to compress the burning and expanding air/fuel mixture, and the engine may also experience detonation/pinging problems, which can lead to catastrophic failure [see “Basics: Detonation” in this issue of HRP]. Conversely, if peak cylinder pressure is reached after the 12- to 15-degree range, the energy that is in the charge will still be burning as the exhaust valve opens, so it will go out with the exhaust as wasted energy.

Tuning the Spark Timing

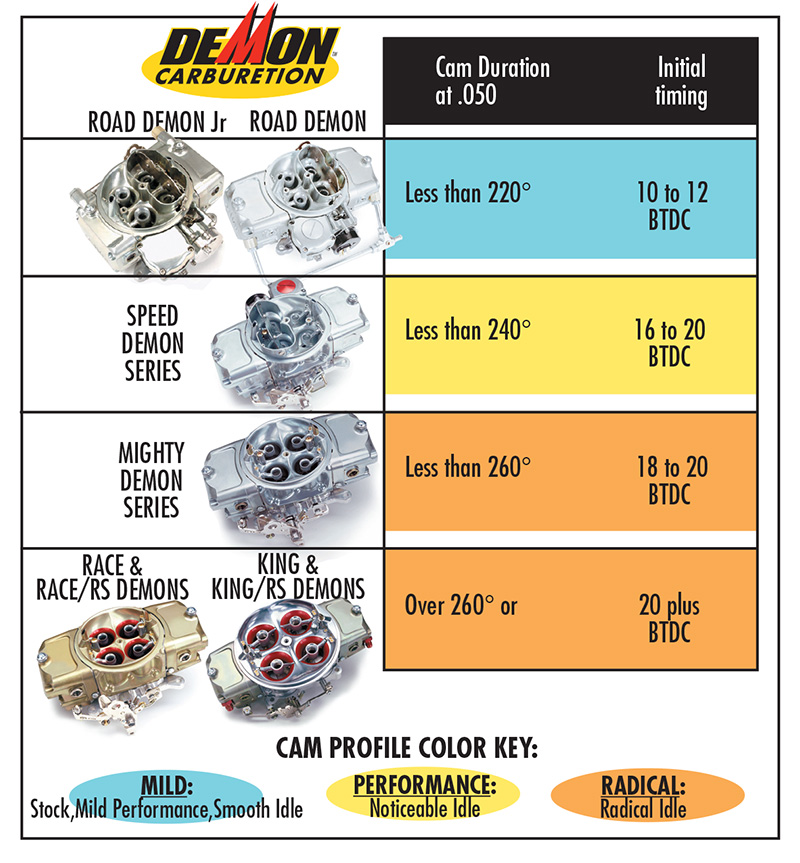

This chart suggests an initial timing setting based on the camshaft in the engine (courtesy Demon Carburetion).

Whenever you are selecting the ignition spark advance curves for an engine you need to consider factors such as the octane of the fuel, the compression ratio, the design of the combustion chamber, the operating range of rpm, the typical inlet air temperature, the weight of the vehicle, and the driving style of the operator. Also, does the engine have a high-performance camshaft? A light vehicle with a powerful engine can in most cases tolerate more spark advance than a heavy vehicle with an under-powered engine. Ignition timing consists chiefly of three parts: initial timing, the mechanical advance curve, and the vacuum advance curve. When added together, these equal the total spark timing advance.

Initial Setting

The ideal initial timing will provide a clean idle and crisp throttle response. One of the best guides for determining this setting on V8 engines can be found in the Barry Grant, Inc. catalog, or on the company’s website under the Demon Carburetor Guide. Typically, 10 to 12 degrees BTDC of initial timing is recommended when the duration of the camshaft is less than 220 degrees @ 0.050 in. of valve lift; 14 to 16 degrees with a camshaft duration of less than 240 degrees @ 0.050 in.; and 18 to 20 degrees when the camshaft duration is less than 260 degrees @ 0.050 in. of valve lift.

The reason an engine with a performance camshaft wants more initial timing is because the air velocities are reduced in the intake manifold due to valve overlap at lower engine speeds, so the fuel may not be fully vaporized. Therefore, advancing the initial timing provides a longer time for the air/fuel charge to burn in the cylinder. The same applies to Air-Gap-style intake manifolds, which are designed to isolate the intake runners from the heat of the engine. This absence of heat can lead to poor fuel vaporization at lower engine speeds, which may cause hesitation and drivability problems. Whenever the initial timing is altered the amount of total ignition advance must be checked and adjusted to ensure that the maximum safe advance settings are not exceeded.

Why an Engine Needs a Mechanical Spark Advance Curve

As rpm is increased, it is necessary to advance the ignition timing. If the spark is not advanced, the burning process in the combustion chamber would take longer than the speeding piston would permit, thus resulting in lost engine power. To give the burning process a head start, the distributor uses a mechanical mechanism to advance the spark as the engine speed is increased. This system is activated by engine revs, which generate centrifugal force in a set of rotating weights, and the rate of movement toward advance is controlled by springs. For most performance engines, the mechanical advance curve that works best should not begin advancing spark before about 1,000 rpm, and advance should be all in by the 3,000 to 3,500 rpm range. Too much advance while engine speed is low can cause harmful pinging or detonation, while too little advance will keep the engine from producing all the power that was built into it.

Most vintage domestic V8 engines (not including those with “fast-burnâ€-style heads) will produce maximum power at wide open throttle (WOT) with a total mechanical spark advance of 36 degrees, while an engine with more modern fast-burn heads will perform its best with 32 to 34 degrees of mechanical spark advance. These same engines will also produce the best fuel mileage under light load and steady-state cruise operating conditions with 46 to 48 degrees of combined mechanical and vacuum spark advance with today’s unleaded gasoline. The factory-designed advance curves tend to be on the conservative side.

A dial-back timing light is a good way to check the advance curve if you do not have access to a distributor test stand.

Vacuum Spark Advance

A hand-operated vacuum pump can be used to help the user check the vacuum advance diaphragm and mechanism.

When a vehicle is driven at low-load conditions such as cruising at light throttle, the engine will need more spark advance to fully consume the slower burning, leaner air/fuel mixtures that are used when fuel economy is a concern. These low-load mixtures are used to offset the slower intake air velocities that result from the throttle only being part way open and the cylinders not being filled as fully as they are during WOT. In addition, the scavenging effect in the exhaust ports that helps to expel the spent exhaust gases from the combustion chamber dilutes the air/fuel charge and slows the burn rate. To exploit this leaner condition and get maximum fuel efficiency, the vacuum advance mechanism adds additional spark timing.

Ported vs. Manifold Vacuum

There are two possible vacuum sources for the advance mechanism, ported or manifold. Tuners often have different opinions on which vacuum source is the best depending on the situation. My choice is ported vacuum assuming the initial timing setting has been selected correctly. Manifold vacuum acts on the advance unit’s diaphragm whenever the engine is running, while ported vacuum is only available once the throttle is opened to an off-idle position far enough to uncover the port. If the engine has a “radical†camshaft, the additional timing advance at idle that you get from manifold vacuum may help the engine idle better, but you need to select a vacuum advance control unit that is fully advanced at a vacuum level that is two in. Hg below that present at idle (in gear, if the vehicle is equipped with an automatic transmission).

Checking Curves

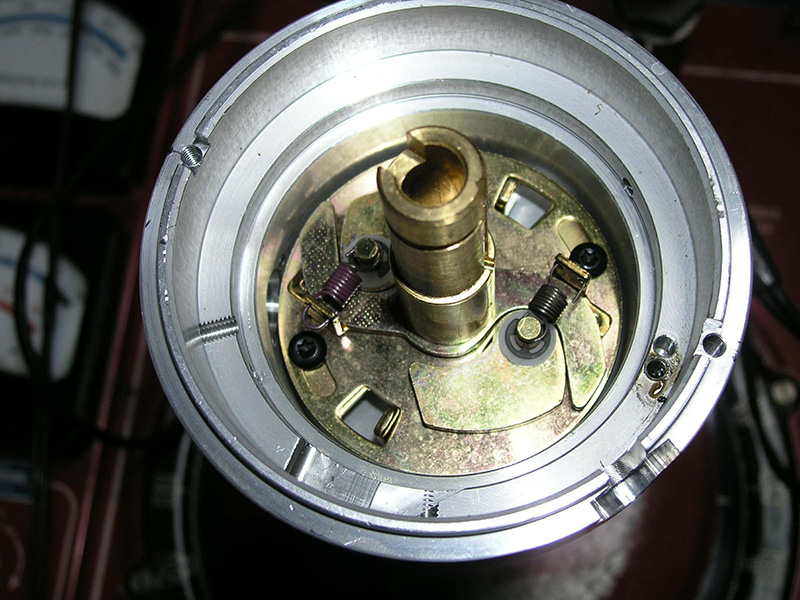

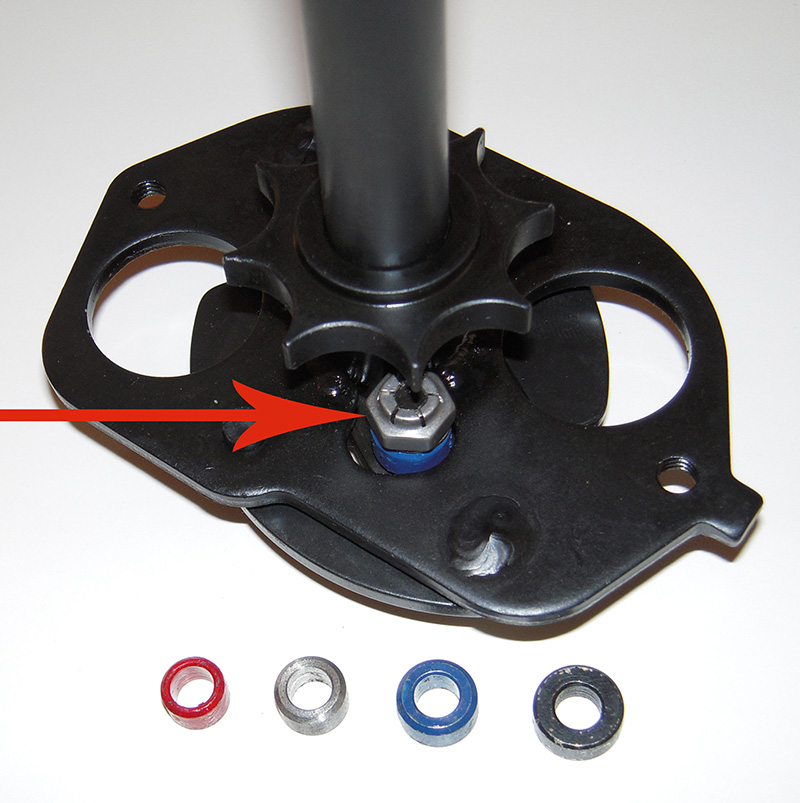

We often modify a points-type General Motors distributor to use MSD bushings so we can get the mechanical advance curve where we want it.

The best way to check the advance curve is with the use of a distributor test stand. These machines are not as common as they were years ago, but almost any shop that works on vintage vehicles will have one, or will know where a distributor can be sent to have the advance curves checked and modified. In the 1960s, almost every shop possessed a distributor tester, so it was easy for the hot rodders of that era to have their distributors re-curved for maximum power. Today, the advance curves of most hot rods remain unchecked, thus their owners don’t know if the spark timing is correct for maximum performance throughout the rpm range. A distributor test stand can check the distributor advance at any rpm from idle to 6,500 rpm or more without having to rev the engine unmercifully, thus it is a lot less stressful on the mechanical components.

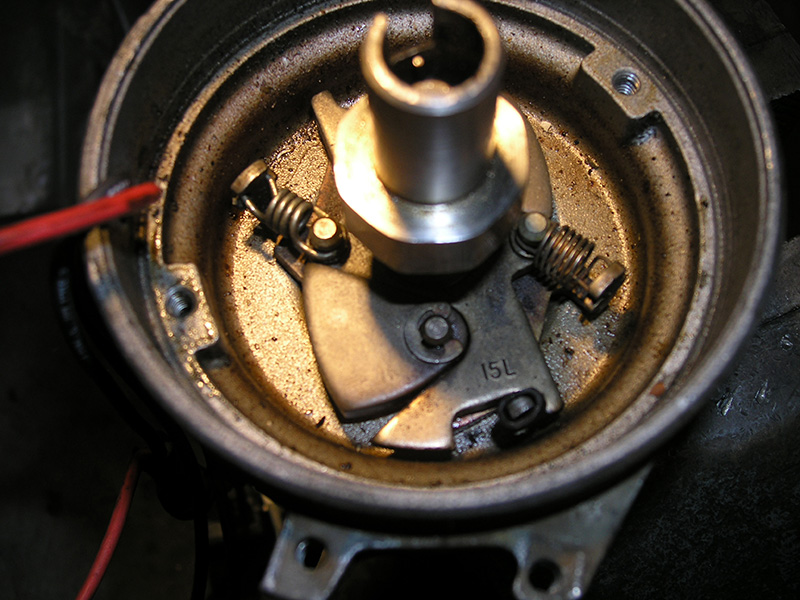

This mechanical advance system from an early MOPAR distributor is somewhat challenging to tune unless you have welding skills so you can build in a stop to limit the amount of advance.

An alternative method of checking the mechanical and vacuum advance curves is with the distributor fitted in the engine. If you’ve got a degreed harmonic balancer, the amount of timing advance can be observed by using a standard timing light. If not, you can use a dial-back timing light, or add timing tape to the balancer. Begin the procedure by disconnecting the distributor’s vacuum hose from the carburetor and capping the open port. Then, observe the amount of mechanical advance in 250-rpm increments from idle until no more advance is forthcoming. To test the vacuum advance mechanism, use a hand vacuum pump (Mighty-Vac, or equivalent) and a dial-back timing light. This allows you to read the amount of advance generated by different amounts of vacuum from one to about 23 in. Hg.

Re-curving Mechanical Advance

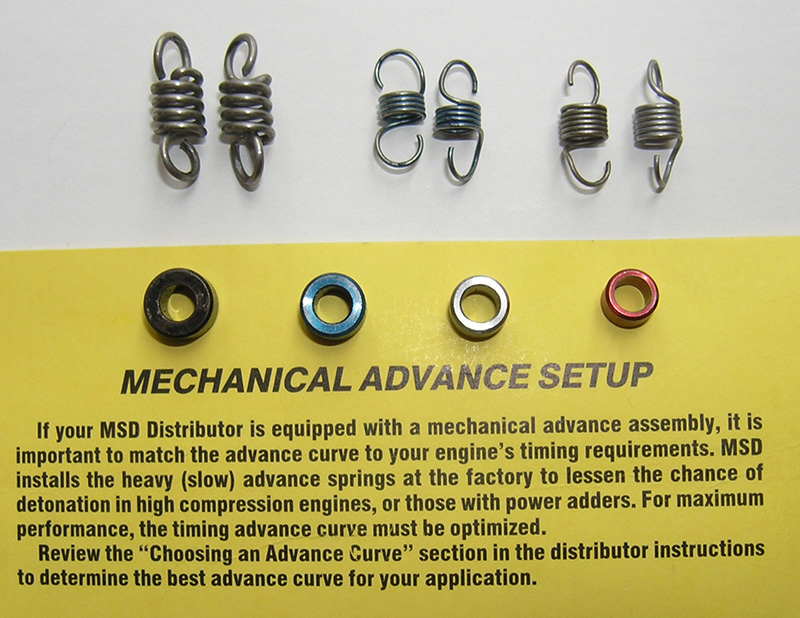

MSD and Mallory make the most tuner-friendly distributors, but almost any original or replacement distributor can be recurved to match the needs of your engine. Most O.E. point-type Ford and GM distributors are pretty easy to re-curve, but there are both original equipment and aftermarket distributors that have mechanical advance systems that can be time-consuming to modify. There is a wide variety of mechanical advance systems that were used in original-equipment and aftermarket high-performance distributors. Some allow the tuner to adjust the amount of advance from the mechanical system with changeable advance-limiting bushings, or that have an adjustable stop, but others require that the tuner have welding skills in order to limit the amount of advance. Large assortments of mechanical advance curve springs are available from companies such as Mr. Gasket that allow the tuner to match the rate of advance to the needs of the engine.

Tuning Vacuum Advance

As I said, gasoline is way different today from what it was decades ago, and most vacuum advance units were designed to work with a blend of fuel that no longer exists. So, they tend to supply too much vacuum-based spark advance for today’s reformulated gasoline. There are a few adjustable vacuum advance units on the market, but sometimes the stop will “adjust” itself over time, so I prefer to use a mechanical stop such as a bushing on the advance pin, or I weld a stop into the advance slot. Don’t forget that if you are using manifold vacuum instead of ported vacuum the advance is dependent on the vacuum the engine produces at idle (in gear if the vehicle has an automatic transmission), so there will always be a steady initial timing setting at idle.

Electronic or Points?

In general, electronic ignition will provide the user with a stronger and more precisely timed spark from cylinder to cylinder than points, but a points-type distributor can actually work quite well. Electronic ignition in general is more reliable than points but is not necessarily foolproof. Some the aftermarket ignition systems can fail if they are exposed to voltage spikes (such as from a battery charger or a plug wire falling off/going open), while others will have spark triggering and output problems and erratic timing issues if the system voltage falls below 12V. It would be wise to always check what the recommended operating voltage is for the ignition system you are working with. The output voltage of the ignition coil is input voltage-dependent — the higher the voltage to the primary side of the coil, the higher the potential output voltage that will be available from the secondary side of the ignition coil and the spark plugs.

Capacitor Discharge & Magnetos

This vacuum advance for an MSD or points-type General Motors distributor has a bushing on the advance pin to limit the advance to the 10-12 degree range.

A shortcoming of a generic capacitor discharge (CD) ignition system is that the spark has very short duration, which can lead to misfire problems at lower engine speeds. MSD has solved this potential problem by firing the spark plug multiple times in the same combustion cycle with its CD control systems. At idle, there may be five or six sparks per plug, then as the rpm increases the number of sparks decreases until about 3,000 rpm where it fires each plug just once per cycle.

Magnetos can give a hot rod a very ’50s look, but a vintage magneto does not have a lot of output at lower engine speeds. So, the spark plug gap for an engine with such a magneto is in the 0.018 to 0.022 in. range. Also, if you want to change the amount of mechanical advance, you will most likely need to send it to the manufacturer.

Good, Cheap Results

Again, the first step in improving the power and fuel efficiency of an engine is to properly tune the ignition system. In my experience, most of the vehicles that are brought to our shop for diagnosis of a carburetor or lack-of-performance problem respond very well to re-curving the spark timing. Once the ignition system is properly tuned, the performance problems are typically cured. The bottom line is that tuning ignition advance will give your customers more performance, economy, and drivability for the money than any other performance-enhancement service you can offer.

Â

0 Comments