Another whole enterpise! While resto work often includes high-performance aspects, it’s about a whole lot more than just trying to go as fast as possible. You won’t find this kind of coverage in any other publication, and we believe you’ll enjoy it and perhaps even be inspired to get into this challenging field. This installment sets the stage with customer contact and initial evaluation.

Here’s where Project “RR†started. It’s actually not a bad retro look. These are light cars, with powerful, rugged, large displacement engines. This is a oneowner, so it’s like another family member. Restoration service is part financial, part time-commitment, and part emotional support for the poor owner who’s horrified at seeing his or her baby dismembered!

There’s a market out there that will test all your skills as a communicator, educator, fabricator, performance mechanic, engineer, and manager, and it’s growing by leaps and bounds as aging baby boomers, flush with cash, are sniffing out and rebuilding the cars of their misspent youth.

Tire crayons are great, aren’t they? We use them to mark the body and then take photos of our marks to document what we wanted to do and where. Small “x’s†mark dents, other marks indicate rust or corrosion, notes are made about what we see, and we get all of our body and paint guys involved so that multiple sets of eyeballs are looking at the same car. Every employee has his own evaluation form, and they all mark them up independent of each other. Then, we all meet up to discuss our findings and start putting our estimate together.

It may be a car they owned in high school. Or, a car a buddy owned that they admired. Or, perhaps it was the car that they fawned over on a showroom floor somewhere while still in their awkward pimply-faced teenaged years. The one they envisioned themselves in, cruising the boulevard with the cute cheerleader sitting next to them with The Beach Boys blaring out of the mono center-mounted AM radio through a single dash speaker . . . who knows? But they are out there and they have the means to do what they want to do and the will to do it, which means there is a growing opportunity for anyone willing and able to manage what can only be described as a long and tedious process. If you’re thinking to yourself, “how hard can it be?,†well, we’re about to share that with you.

To start with, this isn’t just a bring-it-in-and-tear-it-down and just-get-it-done sort of program, which you might think it would be. You’d be foolish to even touch the car until you develop a relationship with the customer and establish some mutual understanding of what challenges you’ll face together as the project unfolds. It’s never as easy as it seems, even with a thorough inspection and evaluation. There are always unexpected challenges on every project, and the customer must trust that you are being honorable with him or her as these are discovered. Restorations and restoration work in general is long-term, often taking eight to 30 months, and expensive, ranging from a few thousand to over $100,000, and the strength of your relationship with your customer is the only thing that will keep you both focused on the same result.

Step One: Initial Customer Contact and Interview

A few decades ago, the look you see here was all the rage. Bright work was blacked out, or made body color, and racy-looking parts were bolted on. Like big hair, it’s a look past its prime.

The process starts with your initial interview with the potential customer. Communication must be clear and founded on trust and a shared objective. You must establish trust and clearly express your dedication to the accomplishment of your customer’s goals. I subscribe to the 70/30 rule during initial customer contact: I listen 70% of the time, and talk 30% of the time. There has been NO communication unless both parties walk away from their meeting with shared and identical understandings of what transpired. In the end, this process, this entire transaction has to be good for both of you. If you can’t agree on an end result, or on an investment amount, then stop — this has to be right for the customer and for the shop. If it isn’t, then walk away. You have the right to pick and choose the people you work with, and this work is difficult enough without electing to deal with difficult people. Don’t bind yourself for a year or two to someone determined to make your life miserable unless you just enjoy being tormented.

A nearby toolbox in the owner’s garage did this. Heavily-weighted drawers would auto open and smack into the side of this 1969 Camaro. While the door was far from pristine to begin with, this has to fall under the category of unnecessary roughness. It’s fine — it got a brand new GM OE door skin.

Our 1969 Z28 had some bad dents and there was a lot of rust present at the lip between the outer wheel house and the quarter panel. In the end, it got both parts replaced with NOS sheet metal.

Managing Expectations

Nearly every customer thinks the work will be easier than it really is, believes that it takes less time that it actually takes, and that it will miraculously cost less than what it will actually end up costing. You must be able to talk about what customers’ expectations are — and you must be willing and able to help manage their expectations, often several times a month as projects develop.

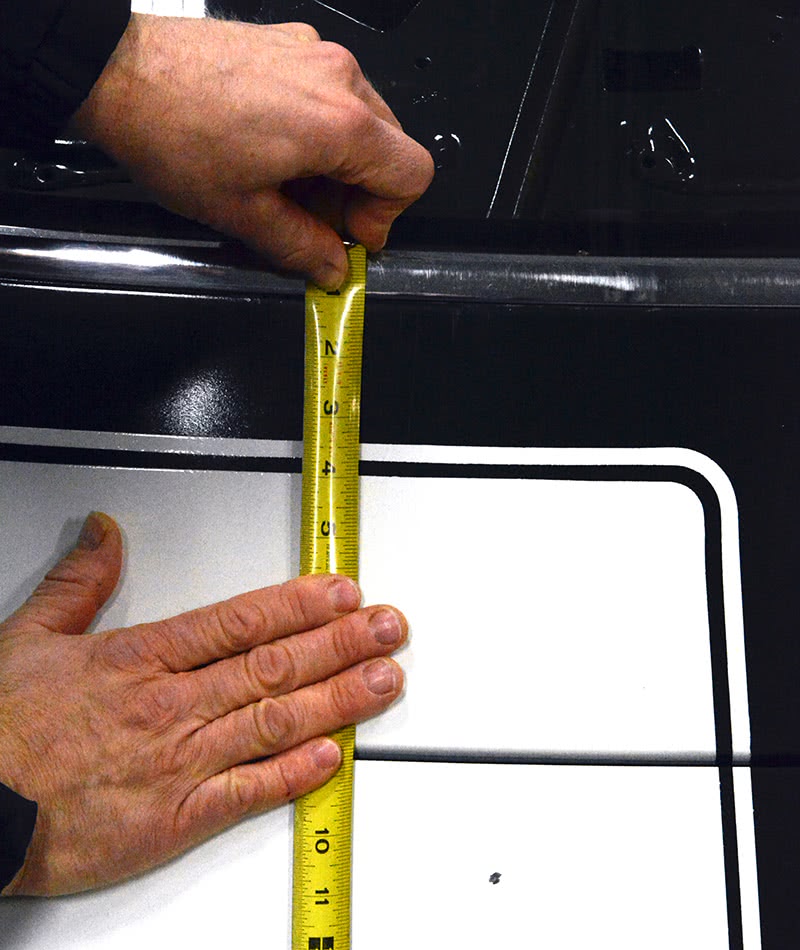

If you’re hand-painting stripes, or if you need dimensions, make sure you’ve got a tape or some other object in the photo so you have a size reference to compare the part under exam to. I’ve used a dollar bill sometimes if I’m away from the shop, or don’t have a tape around and I need to take a picture that indicates scale.

Are we building a daily driver, a show car, a Pro Touring, a Pro Mod, a pure-stock last-nut-and-bolt period-correct restoration, or something in between? If the customer wants a hundred-point perfect restoration, the expectations dialogue continues long after your initial evaluation because a 40, 50, or 60 year-old car has had a lot of hands on it and the care that your predecessors took will largely set the costs of the project.

If you are modifying a car, significantly improving its performance, the level to which you want to take it determines the depth and degree of secondary modifications that have to occur. If you’re building a 600 horsepower engine, you are now forced to upgrade the entire power train, plus brakes, suspension and possibly the frame. Once you tip the engine performance domino, everything else has to follow and the customer must understand this before you begin. There are few things worse than a 600 horsepower street rocket with sloppy steering and marginal brakes. To reiterate, if you’re upgrading the powerplant, you also have to upgrade brakes and steering, the transmission and the differential, the suspension, install frame ties . . . and on and on.

This is a job that you never really master. You master the big parts, but there are always problems and exceptions to every rule. As Napoleon said, “No battle plan survives first contact with the enemy.†Here’s how partial or poorly-done restorations affect your work. Supposedly this was a “rotisserie†job, but you can clearly see that it was a tape-and-spray. Just an example of what we thought we got versus what we really got — and it leaves us with a lot more work to do than what we’d have to deal with if our predecessors had done a little better job. This is why your initial evaluation work is so important. Discovering during the initial evaluation and starting the conversation with the customer before the work begins helps put everyone on the same page earlier in the process.

As you talk your way through this phase, you need to judge the customer’s level of dedication to the project because the time and money spent can be overwhelming. You have to set terms for payment and how you’ll document progress. Restoration work is bill-as-you-go and typically you’ll request at least 50% down at the start of the project and invoice by the week or the month so that the customer can stay ahead on the finances. This protects both you and your customer since you don’t want to be investing in someone else’s property, and he or she shouldn’t have to risk losing a car through a mechanic’s lien.

You need to explain time and materials billing and how everything the customer adds will increase the cost of the project. You’ll need to begin to educate customers about things they wish they didn’t have to know, such as the difference between cheap parts and good parts, and new parts and “just different†parts. Sometimes new means different, not good, and there’s nothing more frustrating on long-term projects than waiting a month for parts only to shake a broken or inoperative part out of a new box. In this business there are cheap parts and there are good parts; there just aren’t any good, cheap parts. You’ll get what you pay for every time and the customer must know this from the beginning.

Besides the investment needed, the biggest expectation to set or adjust is just how long restoration work might take. For some cars, you may spend hours on the Internet or on the phones just locating a single part. I’ve had searches extend for weeks for obscure parts. For popular makes and models, you can usually make a few dozen calls and get most of what you need. If the body shows prior damage or body work that changes your work load and flow in the body shop, if the car is a low-production volume, has rare or unique option codes, or shows signs that it’s been heavily modified in the past (a retired race car?), then all those things will add to your time-to-completion estimate. You’ll be wrong anyway, but try to add time up front to avoid massive disappointment later. Better to say two years and actually complete the job in 17 months than to say 17 months and finally complete it in two years.

How Much Will This Cost?

This is one of the primary questions a first-time restoration customer asks and the answer to it is “it depends.†There is no flat-rate manual for this kind of work. Cost depends on your initial evaluation, what the customer’s expectations are, and what, exactly, you’re going to do. Don’t get backed into a corner on money when it comes to restoration work. Explain that the first price discussed is an initial estimate only, and that it’s subject to change as the project moves along and more needed work is uncovered.

People walk in and say things like, “I just want to get my car repainted. What will that cost?†and the answer is always the same: It depends. How many unknown unknowns will we uncover as we strip the body? Every project grows legs — it becomes more than what it started out to be. In some cases, it’s extra work uncovered as we progress, and in other cases it’s work that gets added as customers change their vision of their completed project. The paint makes the interior look bad, now we’re fixing that. Or, the outside got painted, but the engine bay didn’t, and suddenly you’re pulling the engine to paint the engine bay. Once customers see how good the new work looks, the things they thought they could live with aren’t something they WANT to live with. Between what the customer adds and what you discover as you disassemble, clean, and inspect the parts, the work tends to expand.

Bucket List

This “body in a box†arrived in the back of several pickup trucks, and the first thing we started doing was laying out the big pieces.

Which brings us to step two: the evaluation (see evaluation form sample after this article). I can’t stress enough how important it is to baseline the car before disassembly begins. It’s the only way to protect both you and your customer. Failure to perform due diligence here will cost you time, money, and aggravation later.

The evaluation begins with driving the car — if it’s drivable, of course. Listen, look at, and test everything. Test the charging system, test the lights, work every knob and button. Check brakes, transmission, engine, listen for noises, and feel for vibrations and looseness on the road, and note the overall performance of the car. Create your own evaluation form similar to the one shown here to record your findings. As you can see, there are a lot of things to look at and this is a list that undergoes constant revision at our shop. I’m not sure we’ll ever get it perfected…

In the next installment, we’ll show you what’s involved in achieving the highest levels of restoration, such as our Project ‘69 Z28. Here it is after a summer of driving fun, and it hasn’t had a bath in two months!

If it’s a basket case, you need to have a second conversation with your customer about time and money because in my experience a car that arrives in pieces and parts takes roughly an extra 200 hours to restore. Yes, you read that right, 200 hours and as much as $10,000 extra for the “help†someone tried to provide you with. That’s something you’d better start talking about right up front.

Typically, basket cases arrive in boxes that have been moved among three or four garages over time, and the parts are jumbled up or were poorly organized to begin with. PLUS, there are no photos of what the car looked like before disassembly, and there’s no way to know what worked or didn’t work before disassembly began. With the last basket case we did we ended up with two bays of parts laid out on the floor as we gathered up the “bones†and arranged them from front to rear in an effort to identify what we had and what was missing — and we still missed several items that had to be ordered; and ordered one by one as they were discovered, running up our total shipping costs.

Run a paint film and filler gauge over the entire car to measure paint and filler material thickness. Do a compression test, a cylinder leak-down test, and an oil pressure test (if it runs) on the engine. Record automatic transmission test pressures. Check the level of antifreeze protection, and use a durometer on the tires to see how hard they’ve gotten (60 is a good number, 80 isn’t) if it’s been sitting since Moses parted the Red Sea. If it needs new tires, they’ll add $600-$1,200 to the price.

Cut the old oil filter open and verify that it’s not full of shrapnel, and perform a front steering dry-park test, and check those front suspension parts (these are cars from the dark old days of bad ball joints and worn out tie rod ends, remember?). Use your evaluation document as a guide as you prepare to generate your first estimate.

Have your sheet metal man and painter go over the body, each independent from the other, and mark up every defect they can visually locate in preparation for determining how many hours it will need in the body shop. At this point, assemble your team, compare notes, and start working on your estimate. Everyone should be in on this phase because one set of eyes sees things that another does not, and a shop-wide discussion helps us generate a better overall picture of the scope of the project and a better preliminary number.

0 Comments