A high-performance boat engine for the lakes of Indiana? How hard could it be?

Lake Wawasee, Indiana

Northeastern Indiana is full of lakes. Like so much of the midwest, the glaciers carved out low-lying areas as they ground their way down from the north. As they retreated, they left behind bodies of fresh water. We aren’t “The land of 10,000 Lakes” — Minnesota rightfully holds that title — but we do have over 1,000 to choose from and “going to the lake†is an annual rite for a large number of my neighbors.

It is, for a number of reasons, a recreational activity that defies logic, in my opinion. I can barely keep the cars, trucks, lawnmowers, trimmers, edgers, and other lawn accoutrements running around the old homestead, so why in the hell do I want to deal with a cottage, a trailer, and a boat? There’s plenty of stuff to paint, fix, and keep up with here. Why own a second place 50 miles distant that doubles the workload just so I can go out and compete with the other lake denizens for fishing and skiing space? Or, enter into the local bragging-rights competition on who has the fastest boat? Or, head out to the sandbar and park in the sun swilling beer and listening to competing stereos.

Plus, I have to tell you, the Navy ruined all things water for me. My dad never lost his love of the water despite his destroyer service in the north Atlantic (where he claimed he was so seasick that he would have to have gotten better to die), but my time on or near the ocean took all the mystery out of it for me. I wouldn’t give you a nickel for every lake cottage and boat in Indiana. I have such a well-known aversion to the lake that my friends don’t even ask me to come up anymore. They know that just asking is likely to unleash a five-minute-long profanity-laced tirade about boats and lakes (which might also explain why I have so few friends left). This is fine with me as long as I don’t have to go the damn lake.

Sometime in the late eighties, a nice gentlemen came in and asked if we would consider building him a boat engine, something with a little more power than stock so he could compete in the boat bragging-rights contests I mentioned earlier. We had quite a bit of experience with performance car engines, and that’s how he learned about us. Not knowing the whole story just yet, I said, “Sure! How hard could it be?†And over the next couple of months I found out just how little I knew about boats and boat engines.

A boat, you see, is a water-going dynamometer. It operates at or near full load for extended periods, and water resistance makes wind resistance trivial by comparison. The only advantage a boat has is that it uses the world’s biggest radiator as a heat sink. Otherwise, it’s a design challenge involving maximum sustained wide-open throttle operation at an rpm that is determined by the propeller. The stress of this full-bore load must be tolerated without detonation, or losing oil control or fuel supply in rough water or sharp operating angles — all things I didn’t know at the time.

The gentleman who owned the 24-foot open-bow Bayliner had a couple of young sons, and together they decided they needed more power to play with the faster boats on one of our largest local lakes. In pursuit of this goal, he and the boys had installed a belt-driven supercharger on the Chevy-based 350 marine engine. They were looking for something in the 50 to 60 mph range, as I later learned. A supercharger is a great way to go IF you have the fuel to support it and IF you don’t stick it on an engine with a 9.5:1 compression ratio, as the original engine in this boat had.

At that time, marina gas around here was — let’s just say — variable in quality. It might be marked 87, 89, or 91, but I’m not convinced that was anything other than wishful thinking. When the boat first arrived it was pretty apparent that the engine had sustained significant detonation damage. We pulled it out and tore it down to find the usual suspects: trapped rings, burnt pistons, and intake valves turned inside out. There was nothing wrong with the installation of the blower — they did a great job, but it was too much effective compression and not enough octane that did them in.

After considerable discussion we landed on a 355-cubic inch, 9.8:1 engine with a marine-specific cam and an upgraded intake and carb, naturally aspirated and designed to run on fuel of variable quality. The bill was paid, the boat delivered, and all was fine. For a week. Seems the boat was running about 47-49 mph, and that just wasn’t getting the job done insofar as bragging rights were concerned. The customer (an engineer) had input on the original design and agreed that it was performing as advertised, but it just wasn’t as fast as he wanted it. So, he asked that we redesign it for the blower.

Out came the engine again. A blower cam and pistons were installed and I gave the owner what can only politely be described as a lecture regarding blowers and marina gas. I explained that unless he had control over fuel quality he would be back — again — with a damaged engine. He agreed and said that he and his boys would haul fuel from the gas station to support their speed habit. And for a few weekends they did. Then one fateful fun-filled weekend they ran short and figured that “one tank full of marina gas couldn’t hurt.†You can guess the rest.

We were now several thousand dollars and three engines into this program (counting the original) and the contrite owner was faced with another damaged engine. By now I’d been reading and trying to figure out just what it takes to move a boat this big with a hull this inefficient through the water at 55 mph or more (the customer’s target speed), and it’s a LOT! In fact, it looked like I was just about one engine short of the job! It wasn’t just the engine, it was the prop, the outdrive, and exponentially increasing resistance that was eating my lunch.

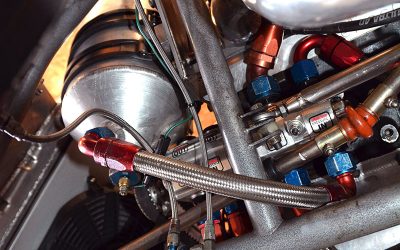

We went to work with our machine shop, the good people at Crane and anyone else with any boat expertise and came up with the best solution we could: a stoker engine with good rods, a reduced base circle cam to clear everything, revised oiling and fuel systems, and as much compression as we felt we could run. It was roughly 384 cubic inches with the over bore, designed to run between 4,400 and 4,700 rpm, and was topped with what looked like a two-foot-long Holley carb with foam-filled bowl extensions to control the gas — and now I had to go to the lake to tune it.

Long story boring, I spent a miserable day tuning, checking, and refining while we bounced over the water at what felt like insane speeds (especially if you’re head down in the engine bay next to a roaring mass of iron and steel). At the end of the day (after putting as much pitch on the stainless steel prop as it would take), it ended up running an indicated 57-58 mph at 5,100 rpm.

It held together for at least ten years in spite of the owner’s benign neglect (it only had about .035 in. clearance from the rods to the cam and I told him to check the Cloyes double-roller timing chain every year for wear, which he never did). Last I heard, it passed from father to sons and finally was sold outside the family to some poor fool who probably still has no idea what’s going to happen when that chain finally stretches enough to let the rods hit the cam.

Is there a lesson here? Yep, there are at least three: One, it’s not always as easy as it seems like it should be. Two, boat folks are a little nutty. And, three, any problem can be solved if you stay with it and never give up. Oh . . . and, four, “going to the lake†is a euphemism for “working seven days a week while telling everyone how much fun you’re having!â€

0 Comments