We’ve seen engines torn down when the real problem was in the ignition system, rod bearings replaced when a wrist pin was knocking, valve jobs done when a timing chain was actually at fault, oil pans removed because of a bad oil pressure sending unit, etc. So, you’d better be very sure you’re right about what’s wrong. Here, we cover the traditional basics, with a note on VANOS.

More and more, we’re seeing BMWs with hundreds of thousands of miles on their odometers that have “never had a head off.†Chalk that formerly-impossible longevity up to several factors: ever-improving designs and materials, better oils and filters, and a precisely-metered fuel mist that doesn’t wash the lubricant off the cylinder walls.

Still, human nature being what it is, and given the incredible number of miles people drive their beloved BMWs, you’re going to be faced with internal engine problems from time to time. If it’s premature, chances are it’s due to neglected maintenance (who, me?), and sometimes a repair isn’t the right fix; replacement is. Regardless, whenever you want to find out what’s going on inside that BMW engine, your diagnostic skills are going to be tested. We hope the following will help you pass.

Comm, eyes, and ears

As with all repairs, careful communication with the customer at the outset is of primary importance, and that’s especially so given the high costs involved in this kind of work. What, specifically, is the complaint? Rough idling, high oil consumption, noises, poor performance, and puddles of oil on the driveway are probably the most common symptoms of something amiss in the engine assembly. Taking a test drive with the car’s owner aboard will help prevent misunderstandings.

An overall visual and auditory examination should come next. You might see or hear something obvious, such as a crushed exhaust pipe, or a sludge-packed oil filler cap. This is related to stepping back and taking a comprehensive, holistic view of the vehicle’s condition and “lifestyle†before you jump to any unfortunate conclusions. For example, we remember having an OHC V8 in our shop with a low-power, rough-running complaint. The car was in pristine condition otherwise, so we immediately engaged our standard diagnostic mode, neglecting to note the odometer reading. After wasting quite a bit of time, we finally noticed the mileage – 243,000! No mystery then that the nylon timing chain tensioning components should have disintegrated, putting valve/crank synchronization out of whack. Lesson: Look at the big picture. Besides mileage, how was it maintained? Has anybody else ever been inside that engine? What kind of driving has it been subjected to? Highway cruising takes a lower mechanical toll than commuting in stop-and-go traffic, or short hops.

A bulletin search is another crucial preliminary. It would be embarrassing to miss a pattern failure.

The top diagnosticians we know have commented that getting as much information as possible from the full assembly prior to teardown gave them the best chance at locating and repairing the problem once they were down to the dirty parts. In other words, collect all the clues and evidence you can before rendering the engine inoperable.

Of course, you’ll want to see what your scan tool, either hand-held or PC-based, tells you early on since it’s so easy. But something like an OBD II P0300 code (random misfire) doesn’t really point you in any specific direction. So, here we’re going to talk about more direct and time-honored troubleshooting.

Squashed air

Compression is one leg of the tripod that supports internal combustion, just as important as fuel and ignition. Regardless of all the technology in modern engines, that basic physical fact is exactly the same now as it was in 1876 when German engineer Nikolaus Otto patented the four-stroke cycle. So, underneath that high‑tech exterior there’s still just a piston pump.

First, listen carefully, both to what your brain is trying to tell you about the symptoms and to the engine itself. Asking a few question in your head will help: Is the idle uneven? Are power and fuel mileage declining? Does it smoke and use a lot of oil? How about backfiring, hard starting, or high emissions that resulted in failure of a pollution test? Start it and note if it cranks unevenly or takes a long time to fire up, both of which suggest poor compression.

Today’s cars typically go a long, long way before they develop conditions that reduce compression. There will always be exceptions, however. Then there are vehicles that have exceeded that long, long way, but are still worth fixing. BMWs are a prime example of that. People love them, so will commonly want to get them back into good shape at almost any price.

As far as probabilities are concerned, the most likely culprits are burned or sticking valves, valve train or cam drive or lift troubles, failed rings, and damaged pistons. A violated head/block seal, which was once a common breakdown, is seen much less frequently since BMW adopted MLS (Multi-Layer Steel) head gaskets, although it still happens due to faulty installation during service or severe overheating that warps castings.

Use your scope to find out if the ignition system is in good shape ‑‑ we’ve seen heads pulled when the real culprit was a bad plug, wire, or cap. Then, do electronic or relative compression and cylinder balance tests.

Of course, many old-fashioned technicians like to get an initial idea of the situation with a manual cylinder balance check. Pulling one plug wire at a time to find out if a particular hole has little or no effect on idle quality and speed when disabled is about the most useful troubleshooting trick known to man for older cars, especially where there’s a definite miss. That is, if you remember to disable whatever computerized idle stabilization device is present. And use well‑insulated boot pliers or that hot‑stuff electronic ignition might blow your pacemaker. With coil-over direct ignition, of course, this isn’t a manual operation anymore, requiring electronic equipment. You can, of course, kill injection instead of spark.

Vac knack

A vacuum gauge can be helpful at this point, although its readings may be inconclusive or ambiguous. You’ll get the most useful results at curb idle speed with the engine fully warmed up. A typical healthy powerplant will produce 15‑20 in. Hg.

A steady low reading may be caused by a vacuum leak or late valve timing due to a worn or jumped camshaft drive mechanism. If the needle drops at regular intervals, suspect a leaking valve, whereas if such drops occur irregularly, a sticking valve is indicated. Floating over a wide range suggests a bad head gasket seal. Rapid needle vibration is evidence of loose valve guides.

Since backpressure can interfere with cylinder filling, check for a clogged catalytic converter or crimped pipe by holding 2,500 rpm. The reading will drop when you first open the throttle, then stabilize. If it starts to fall afterwards, there’s probably an exhaust restriction.

PSI

Although the results will usually be inconclusive, the use of an old-fashioned vacuum gauge can at least give you an idea of an engine’s pumping ability. Compare the readings to those in the data stream.

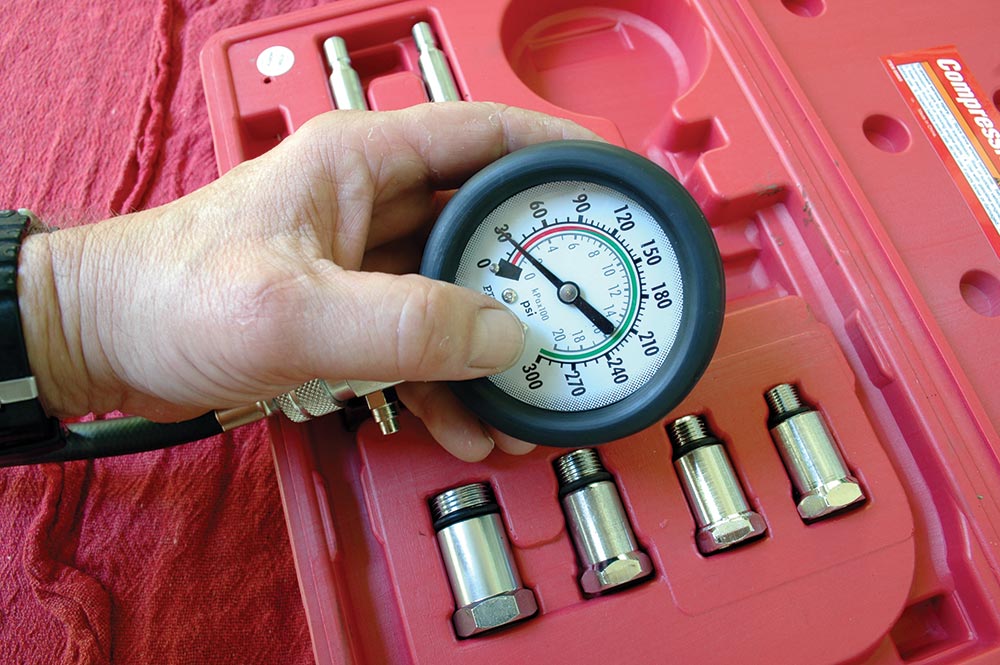

Whether or not you’ve isolated a cylinder or two as the source of the problem, it’s time to unscrew the spark plugs and do a traditional dry/wet compression test. Old hat? Maybe, but you’ll know if there’s a problem even if nothing else says so.

You already know how to do a compression test, of course, but here are a few subtleties that’ll help you avoid a costly mistake:

- Blow out the plug wells or debris could temporarily hold a good valve off its seat.

- Since you’re dealing with aluminum threads, better loosen those plugs with the engine cold, then just snug them back down enough to fire it up.

- Readings will only be accurate at normal operating temperature.

- Pull all the plugs to make cranking easier.

- Make sure the battery and starter are up to the task of achieving normal cranking rpm.

- Block open the throttle plate.

- Disable the ignition. Not only will open secondaries zap the electronics with more voltage than they might be able to take, it’s also asking for an explosion.

- Even though the clear‑flood mode is supposed to halt injection during WOT (Wide Open Throttle) crank, you can be doubly certain to eliminate gasoline spray by shutting down the fuel pump and blowing the residual pressure through the rail’s test Schrader into a rag, or by unhooking injector connectors.

- You need at least four pulses per cylinder.

Record the first and fourth pushes of the needle. Why? Let’s assume a normal reading of 185 psi. A constant (unwanted) hole in the cylinder will allow pressure to built uniformly with each push. For example, you may see 30-60-90-120. This tells you that the leak is there all the time and is uniform in size — a burnt valve, perhaps, or a badly blown gasket. On the other hand, 90-100-110-120 tells you that the cylinder is sealed up to a point, after which something breaks down or leaks. This is typically how rings fail, but a leaky head gasket will also behave this way. As a rule, the first push should be half or more of the fourth push. For our 185 psi cylinder, we’d expect to see 120-145-165-185, or thereabouts.

Test dry, then wet — add a tablespoon of oil to each cylinder. Wet testing isn’t always effective, however, because the oil may not get evenly distributed around the top ring. If a low reading jumps substantially after the addition of a few squirts of oil, you’ve got a ring/bore problem. On the other hand, if wet readings are only slightly higher, and this rise is roughly the same for all cylinders, valves are implicated.

The difficult part is judging how much variation among cylinders, or between dry and wet readings, represents a serious problem. Say you’ve got 100 psi in one, but about 140 in the others, and adding oil brings them up only five psi or so. Is a valve job necessary?

There’s still nothing that can give you a better inside picture of the pressure tightness of that cylinder than the traditional dry/wet compression test. But don’t just look at the max reading. Instead, observe how the needle jumps with each of four impulses.

That depends. Obviously, the low one is leaking somewhere, possibly through an exhaust valve, and erosion is going to make it get worse pretty rapidly, so the proper thing to do is get in there and attend to the seats and faces. On the other hand, if it’s not bad enough to cause a miss yet, and the customer has been frittering away his or her money on luxuries like food and shelter so can’t afford major work this month, maybe he or she can simply live with it. Just make sure the customer understands that no amount of tuning or other external attention will make that engine run any better or go any farther before that cylinder loses it altogether. At least there’s some good news ‑‑ the rings are okay.

Poor pressure in two adjacent cylinders should make you think about a blown head gasket. Confirm this by looking for coolant in the oil or on the spark plug, and by checking for evidence of compression in the cooling system. Hold the probe of an exhaust analyzer over the radiator filler neck to see if you get an HC reading, or remove the thermostat housing and water pump belt, then watch for bubbles. Another possibility is one of those water-filled testers you stick in the radiator neck — again, bubbles are the tip off.

Escape volume

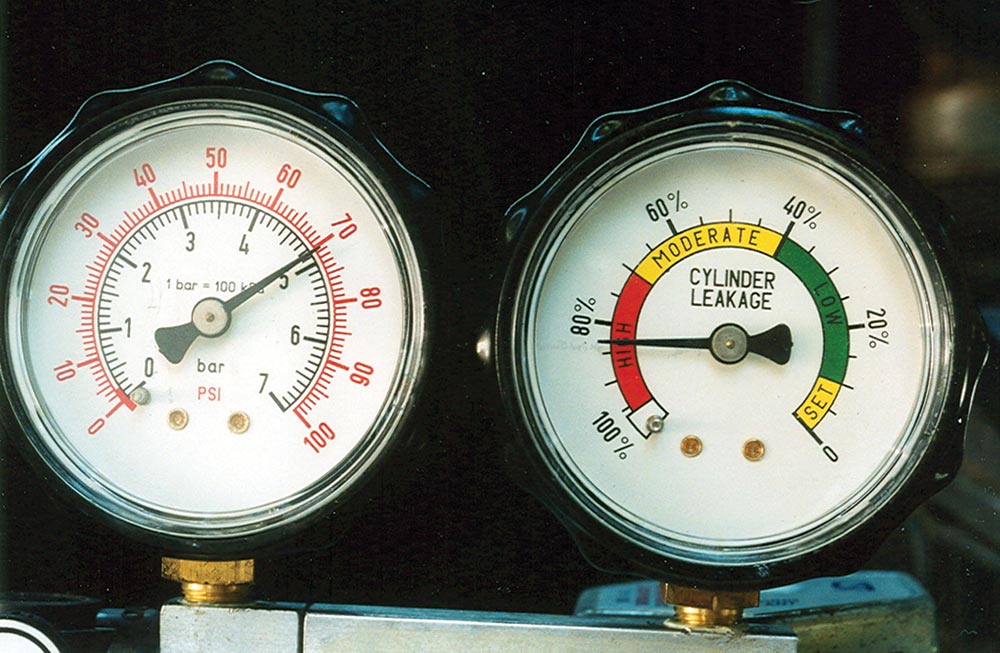

Another excellent troubleshooting procedure is the cylinder leak-down test. The gauge set lets you know what percentage of the pressure being pumped into the cylinder is escaping.

Gauging compression isn’t the only time‑honored procedure that’s still useful for assessing an engine’s ability to squeeze air. There’s also the cylinder leakage test, which is done by pumping maybe 90 psi into the spark plug hole with the valves closed, and listening to where it escapes. Hissing at the intake points to the inlet valve, and the same sound at the tailpipe indicates the exhaust.

There’ll always be some noise at the oil filler hole because even the best rings can’t seal completely (gaps, you know). The trick is to tell when it’s excessive, which you can probably do by comparing cylinders. And this test is great for fingering a leaky head gasket ‑‑ remove the radiator cap, look for bubbles, and listen.

An improvement on this theme is the use of a gauge that lets you know what percentage of the available pressure is escaping, which is called a cylinder leak-down test. With the plugs out, bump the engine over until the cylinder in question is at TDC of its compression stroke. Use a regulated air supply of 70 to 100 psi, which you compare to the pressure the cylinder is capable of holding. Older engines tend run some pretty high leakage numbers, so look for consistency and don’t worry too much about those big numbers if the engine is running smoothly at idle. We’ve seen engines with uniform leakage numbers of 50% perform just fine. We’ve also tried to fix those numbers, and found out that going from 50% to 20-25% made no appreciable difference in the way the engine ran. Newer engines typically produce low numbers — under 10%. If you get a high reading on a cylinder with no recorded misfires, check for carbon. Crank the engine over a few times to dislodge particles and repeat the test. If the numbers come down, you may be fighting carbon.

There’s more to throw into your mental threshing machine before you make your grand diagnostic pronouncement. Anything that holds a valve open, such as a broken spring or a sticking guide, will certainly cause a low compression reading. While these can usually be fixed without removing the head, chances are the valve is burned to a crisp (it can only cool when closed, after all) and/or bent. You can try making the repair and see what happens, but there’s no guarantee of success.

Low cylinders that don’t produce more pressure after oil has been introduced into them may not have valve sealing trouble. A wiped cam lobe or other valve train failure can result in a miss because the cylinder isn’t being properly packed. Check lift before you start unscrewing head bolts.

Absolutely no compression in a cylinder does not necessarily mean a valve is stuck open or burned away, either. There could be a hole in the piston, and we remember an engine that was still running, albeit roughly, even though the piston was entirely gone along with the whole rod so that when we yanked the head we were looking down on what was left of the crank pin.

In cases where that BMW suddenly refused to start and you got weird compression readings, a jumped timing chain is a more likely possibility than bad valves, which deteriorate gradually. If the powerplant isn’t freewheeling (that is, the valves hit the pistons if they’re out of synch), however, you might to have to remove the head anyway for the replacement of some bent stems.

Who’s knocking?

You know it when you hear it: a deep, hollow sound, not at all like valve train click‑clacking. The universal term for this disturbing noise is knocking, and it’s perfectly appropriate because it makes you think of knuckles on a wooden door. And it’s a pretty sure indication of a problem in the engine’s foundation, the precursor of certain catastrophe.

But conclusion jumping is a dangerous sport. Your plans for a simple rod bearing job will have to be greatly modified if the crank turns out to be bad, the rod big ends are stretched so there’s no crush factor to keep the bearings from spinning, or the knock is really emanating from a loose piston pin fit.

Identifying the source of that nerve‑jarring knock can be tricky, and the biggest challenge is distinguishing between a loose rod bearing and a worn‑out wrist pin. It’s indeed unfortunate that one sounds pretty much like the other.

With a little patience, however, you should be able to determine what’s at fault. Use a stethoscope to listen to the engine while it’s idling hot. A rod bearing makes more noise at the oil pan than elsewhere, and a wrist pin more racket up on the water jacket. Hold rpm at 2,500, jerk the throttle open and let it snap closed. This will accentuate rod knock, whereas pin noise won’t change very much.

Pumping liquid lube

Oil pressure sending units aren’t always 100% dependable, so we like to back up our diagnoses of bottom-end problems with readings from a mechanical gauge. Make sure the engine’s fully warmed up.

Next, check oil pressure by screwing in a mechanical gauge.

Specifications are usually given hot, at idle and between 2,000 and 2,500 rpm. Why low and high speed? Pump speed naturally affects the volume pumped, and, of course, an oil pump generates volume only. Pressure is built by trying to push that volume through small spaces, such as the bearing clearances. Because the pump is of the positive-displacement variety, it’ll move anything you put into it, pressure will rise as the discharge is restricted up to the set point of the pressure relief valve. The old standard of 10 psi per thousand rpm still works fairly well, but in an effort to reduce horsepower losses, late models often have reduced maximum pressures. Always refer to specs.

Make sure you’ve let it run for plenty of time before you render a verdict ‑‑ 50 psi cold can turn into 5 psi hot. Also, don’t rule out a pump or bypass relief valve problem, or the presence of low viscosity oil (we once knew a guy who liked to fill his crankcase with ATF). The relationship of flow to bearing clearance is important. Assuming that normal clearance is .001 in., flow will increase by a factor of five if you just double the clearance to .002. If you go to .004, oil flow increases by a factor of 25. Interesting, particularly in light of the fact that most engines won’t knock at .004 in. on the rods. Sooner or later, the pump’s volume is exhausted, pressure drops and the light comes on.

If the pressure fluctuates, think low level, entrained air, or suction leaks. Maybe the pan is running dry due to the installation of a high-volume pump. Or, perhaps a massive internal leak is draining the pan. A high-volume pump needs more pan capacity because at high rpm the oil is pulled out of the pan and held in windage. The oiling system is just that: a system. More is not always better unless all the components are matched. Any suction leak between the oil pickup and the pump will create fluctuations, as will air pulled in due to excess flow through worn-out bearings that sucks the pan dry.

If oil pressure is low all the time, suspect an internal leak such as bad bearings, or a leaky oil gallery plug. A worn-out oil pump can cause low psi, but as it’s the best-oiled piece in the machine it’s not a good sign for the rest of the internals.

If pressure’s low at idle, but okay at high rpm, the pressure relief valve is probably stuck open. In cases where the psi is fine at idle, but low at high rpm, think restricted pickup screen, although a suction leak could be the culprit. Pressure high all the time? The relief valve is probably stuck shut, which can blow the filter.

Carbon, maybe

Whether the mechanical diaphragm type, or one of the new electronic amplified versions, a mechanic’s stethoscope is about as indispensable as it gets where nailing down noises is concerned.

Killing cylinders, either with a scan tool or manually, is often mandatory for nailing down the offender. A rod knock tends to quiet down with the cylinder killed, but a pin tends to get louder. Still sounds the same? You may be dealing with a carbon knock. If a heavy carbon ridge has formed above the top of piston travel, it can eventually force a violent rock-over, producing a harsh, loud piston-slap type of noise. Also, carbon can build up in the quench areas to the extent that the piston actually contacts it at TDC, which causes a mechanical knock or even a slap knock. In the early stages, a carbon knock will mimic a slap in that it will go away as the temperature comes up.

We’ve seen enough of this lately to recommend de-carbonizing as a first step. You may have to treat the engine two or three times. Today, we have such good chemical intake tract and combustion chamber cleaning systems that everybody’s abandoned grandpa’s manual de-carbonizing.

One of the techniques used to find out if that noise is carbon-related is the floating throttle rev test. Take the engine up to about 2,000 rpm, snap the throttle open to increase cylinder pressure, then rapidly close it to pull high intake vacuum. Watch that rpm — it’s easy to over-speed the engine. What you’re trying to accomplish is loading and unloading the pistons, pins and rod bearings. You have to do this rapidly from snap open to closed in order to achieve maximum load. Picture the internals of the engine, and you’ll see what you’re trying to do. You need to punch the piston down, then suck it up. If there’s mechanical looseness in the rod/piston/pin, the rap will get a lot louder as you do this. If the noise remains constant (other than going away some as it heats up), it’s probably carbon.

Petroblaze

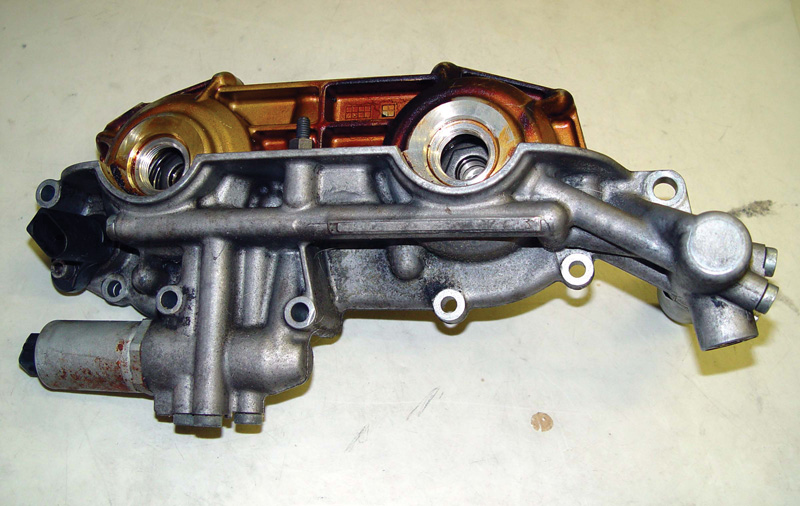

While this double VANOS unit exhibits great engineering, it’s still vulnerable to poor maintenance.

As we all know, excessive oil consumption is usually due to bad valve stem seals or guides, although since the adoption of Viton seals that’s not nearly as common as it used to be. But rings still fail. Unfortunately, you can’t check an oil control ring because it’s the third one down. The compression rings may be fine, but the oil ring may be varnished, jammed, or “unitized.†Valve guides or seals also cannot be effectively tested. As a rule, if it smokes on start-up or after a long, hard decel, it’s probably guides or seals. If it smokes on acceleration, it’s probably rings.

Variable Nockenwellensteuerung

VANOS, the system whose name is derived from the German words in the above subhead, has been around a lot longer than you may think. BMW first introduced it 23 years ago, and double VANOS appeared in 1996. It’s always provided a perfomance edge to the engines so equipped, and has proved to be pretty dependable. That is, except in cases where regular oil maintenance has been neglected. Plenty of oil pressure is needed for proper system operation, so anything that interferes with that will cause troubles that may be hard to pin down.

We covered VANOS diagnosis in-depth in the March, 2013 issue of the bimmer pub, so we’ll just say this here: The presence of this system gives you even more justification for stressing the need for proper maintenance to your customers than you ever had before.

0 Comments