Continuing the finest, most technical automotive writing you’ve probably ever seen, the second part of Greg’s article on high-performance rocker arms covers angles, designs, materials, techniques, coatings and more. Plenty of great photos, too!

Opposite Page: With aftermarket rocker systems and high-lift cams, you have to have enough clearance to allow the pushrod to articulate in the pushrod seat without side loading. Also, make sure to check the pushrod clearance where it nears heads and intake through at least two engine rotations. You don’t need a lot of clearance here, but the pushrod cannot sustain any side loading without breaking or jumping out of the seat – 0.010 in. is more than enough.

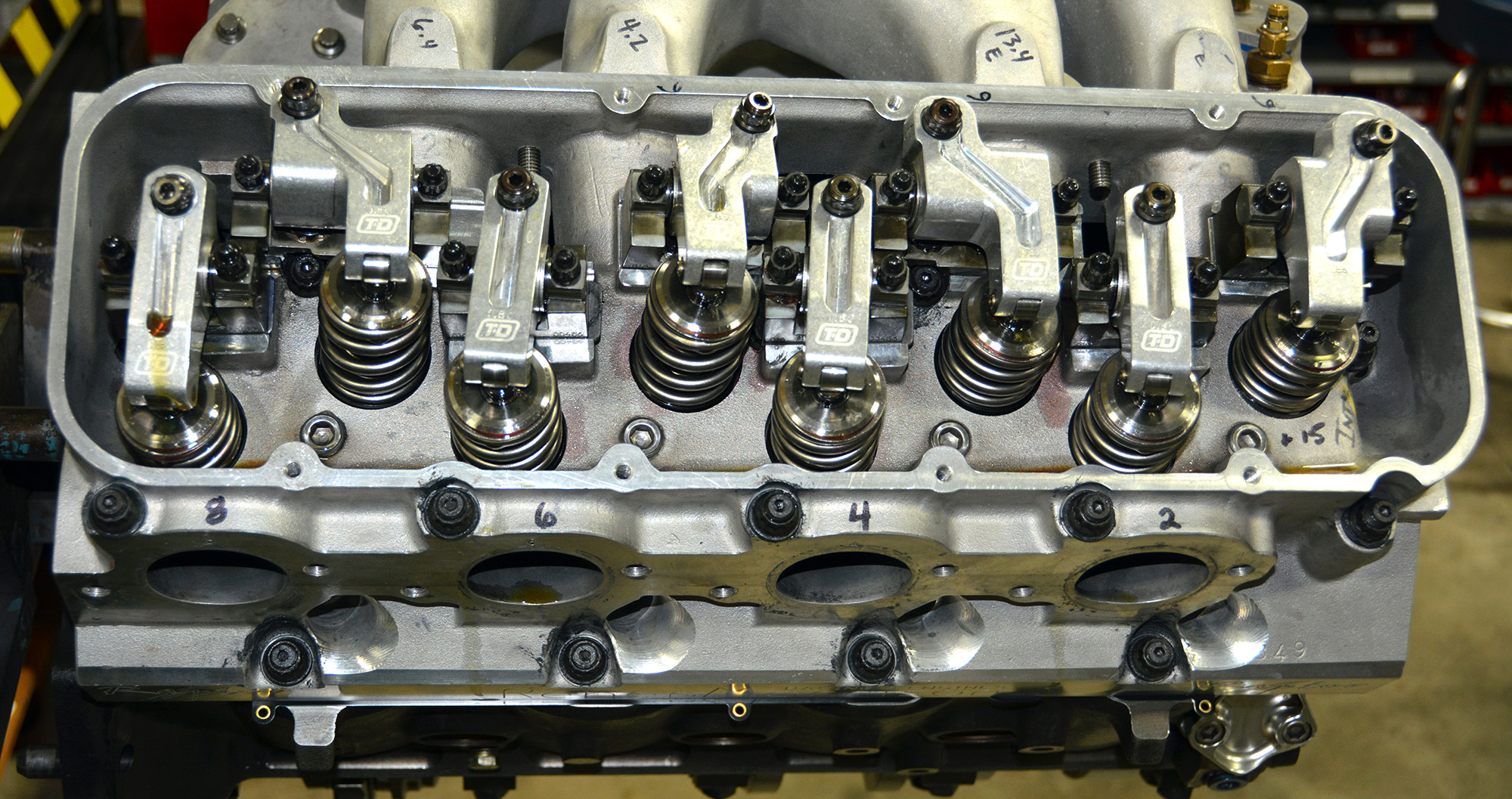

Ask ten people for their opinions on correct valve train geometry and you’ll likely get ten different answers. Here’s the problem: The valve end of the roller rocker is moving in an arc and the valve is moving in a straight line, which means that the roller is going to move across the top of the valve to some small degree no matter what you do. Most agree that correctly adjusting rocker travel by raising or lowering the rocker shaft centerline relative to the top of the valve and changing the length of the pushrods until you get the minimum amount of transfer motion across the head of the valve is at or near the correct geometry for that application.

More Movement at the Valve by Optimizing Geometry

Here are the components removed from a T and D roller rocker body. The two needle bearings are pressed into the body leaving a common channel between them. The solid axle and nose wheel is pressed in and retained in the nose – I had to cut it out to remove it. It’s not field-serviceable. The adjusting bolt and lock nut to secure it after valve adjustment are the last of the parts that make up this exhaust rocker. The center axle, retaining “C†clips, and stand are not shown.

Without going into great detail about how to make this happen, let’s just say this: You’ll know when you’ve optimized your rocker stand heights and your pushrod lengths because when you get it right you will have the narrowest possible track across the top of the valve and greatest amount of valve lift as measured at the retainer. Ideally, you will also be exactly halfway through the net lift as measured at the valve when the centerline of the valve end wheel is centered on the valve stem and a line drawn through the pivot center and nose wheel center lies at 90 degrees to a line drawn up through the center of the valve. This also ensures that maximum valve acceleration is occurring at half lift. Of course, this means that your valve stem heights will all have to be the same if you’re on a full shaft system.

Need to Know

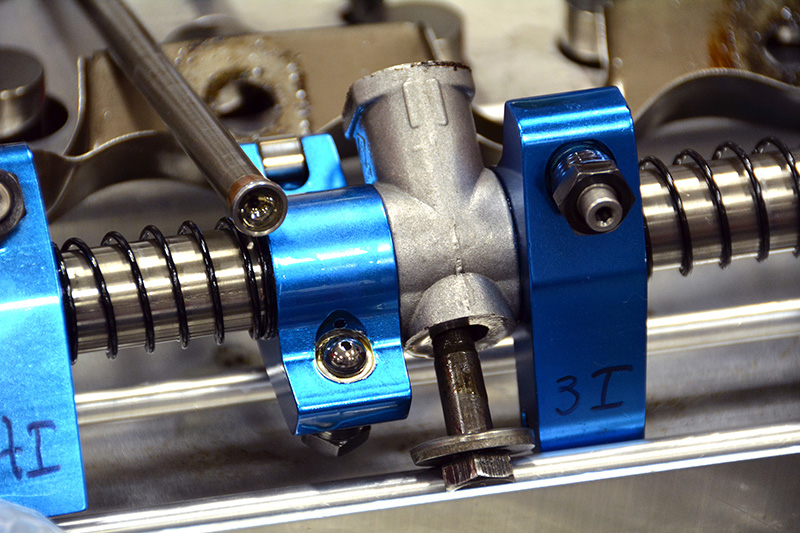

This Comp Cams shaft rocker system is for a 440 Chrysler, and it’s an affordable alternative to one that’s fully-rollerized. The bushings ride on a chrome-moly shaft and the solid axle nose wheel reduces friction and valve guide loading.

In spite of the name, roller tips don’t necessarily roll. Depending on spring load and cylinder pressure, they’re more prone to skipping and skidding. In fact, it’s not that it could roll that’s most important; it’s that the roller makes the valve end of the rocker closer to a fixed length by using a single line contact point on a wheel, like a roller lifter does on a cam. If you look at a typical production rocker, the face that rests against the valve stem is a long, slightly curved surface, like the sole of a clown’s shoe. As this “shoe†moves to full open the effective length of the rocker arm actually gets a bit longer. It would be the same as going from standing flat-footed on the ball of your foot, located midway back on your sole to standing on tip-toes. Using this analogy, you can clearly see that the rocker gets longer by the distance from the ball of your foot to the end of your toes as it moves from closed to open. With a properly-adjusted roller rocker this effect is minimized.

The oil for the nose roller and valve spring is supplied by the shaft through the common channel in between the bushings, and discharges out of the top of the rocker body and out over the roller, retainer, and valve spring.

The other benefit of a roller rocker is reduced friction (even if it doesn’t roll, it’s a lot less material in contact with the top of the valve stem), which translates into lower oil temperature, less shear, heat, galling, and guide wear since it doesn’t exert as much side loading on the stem driving into the guide. A roller rocker can reduce wear materials from the rocker pivot, nose, and valve guide that ends up in the engine oil for the filter, or God forbid, bearings to gather up.

Materials, Construction Techniques and Coatings

There are a number of options when it comes to roller rockers. You can find them bushed at the central shaft or trunnion, single-shaft systems or individual shafts and stands, a fully needle-rollerized shaft, a solid axle nose, or a fully needle-rollerized nose for use with high spring pressures in high-lift applications, or for smaller diameter valves. Valves measuring .312 in. (11/32ths) or smaller are more likely to need fully-rollerized nose wheels to prevent a single axle style roller from stalling and skidding over the valve stem tip.

Most rocker systems are steel or aluminum. The stands, shafts, central axles and adjuster bolts and nuts are steel or tool steel, while the bodies are steel or aluminum, heavily radiused and shot-peened in many applications. Low friction or long wearing coatings are also available. There are so many options available from so many firms that you’ll just have to do your homework before selecting the system that you think will work best for you. I’ve used Comp, Crower, T and D and Jesel for many of the engines I’ve worked on but I would tell you that each has advantages in price, availability, or quality so you’ll just have to shop. There are also some advantages in design as well, with some companies offering ratios that others don’t and offering some rockers that have been constructed with the arms intersecting the main body at different angles that might make getting your rocker geometry correct a little easier.

A Little Bearing Science…

Bearings come in a number of varieties: plain, sliding, Babbitt, coated, and roller element. For the most part, we see roller element bearings in the transmissions, differentials, and transfer cases of most vehicles, but in racing applications we use roller element bearings in the form of needle bearings in a number of other places. Roller lifters, roller rocker systems, and in some cases we even substitute them for the plain Babbitt bearings used to support the camshaft.

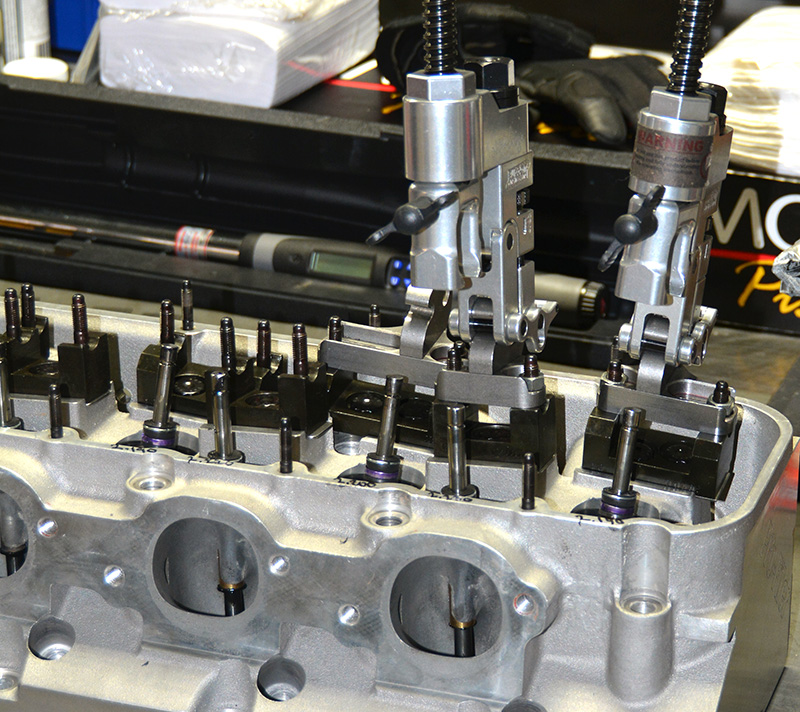

I take everything apart and double-check it. I want to verify bolt torques, I want to see that the shaft is mounted correctly with the oil feed holes down, and I want to see that everything is clean and lubricated. The thing you don’t check will be the thing that causes you a problem.

Needle bearings are so called because they are a roller-element bearing with the highest roller length-to-diameter ratio of all roller-style bearings. Roller bearings come in ball, straight roller or tapered roller, and each has certain advantages that dictate where and how they are used in an application. Other than very low frictional characteristics, the advantages of using needle bearings are that they have high load capacity (even higher than a single row ball or straight roller of similar outside diameter, which might surprise a lot of people) and come in caged designs that are well suited to high speeds and moderate loads with good tolerance for shaft alignment and deflection issues.

The Practical Side:Â Installation and Upkeep

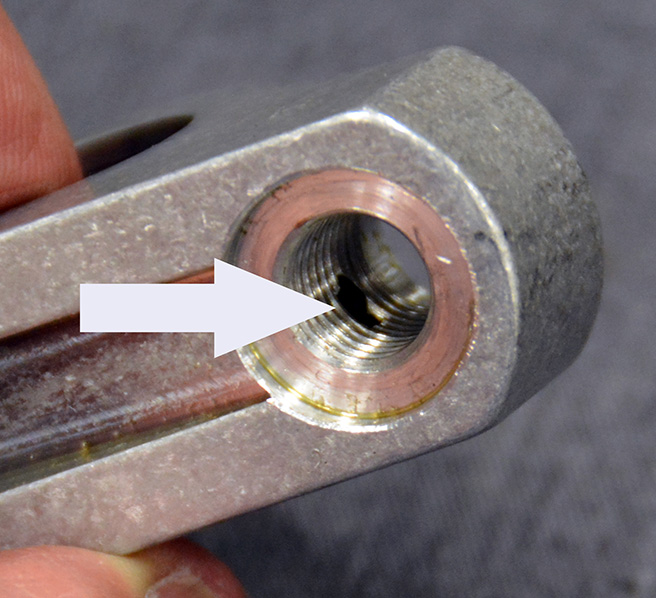

The hole from the pushrod bolt passes through into the common channel, which is how oil moves up from the pushrod, between the pushrod and cup, into the common channel where it lubricates both trunnion needle bearings, and then out through the common channel to spray over the nose roller and valve spring.

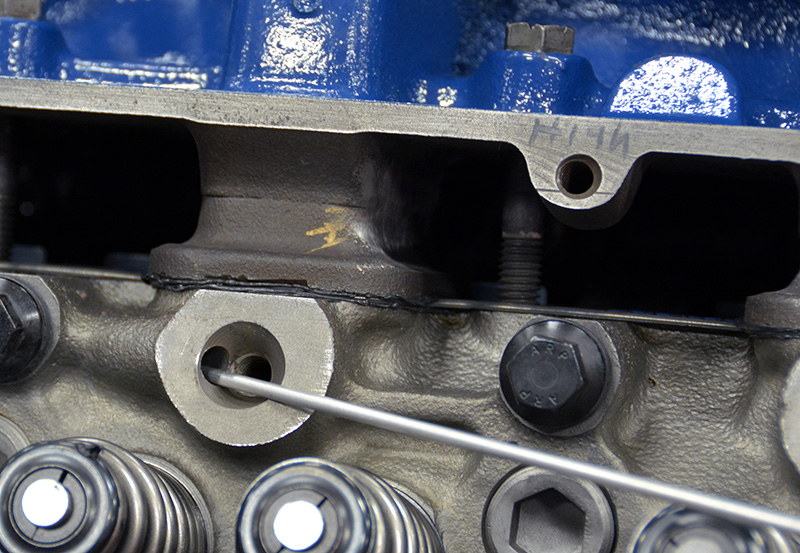

When you first install your roller rockers, there are a few things I recommend. If your application uses individual rocker stands and those stands end up bolted into a bolt hole that intersects the intake port just stop and Helicoil those holes before you even assemble your heads. Helicoils by brand name or any other threaded insert tooling is stronger than aluminum because its larger outside diameter spreads out the load. A lot of the stand mounting bolts will torque down to 60-85 lb. ft. and you’ll just end up stripping the hole, usually when you’re repairing something and really short on time. Trim your bolts so that they are just flush with the roof of the intake port because at speed that’s where the air flow runs, up along the intake roof and you don’t want anything protruding into the port.

While the stock set-up on an FE Ford and Dodge 440 feeds oil up from a passageway drilled though the head, you can reroute the oil depending on if the lifter galleries are bored end-to-end for oil feed and if you changed the pushrods to drilled pushrods in place of solids. If you divert the oil up the pushrod, you’ll need to restrict the oil feed from the head to something around .040 to .060 in. to keep from flooding the top of the engine. You’ll want a little oil in the shaft, but much less than the .095 in. or so that the head gasket hole restricts it to.

Decant the parts, do your inventory and clean everything. Chase all the threads, or at least make sure the threads engage in the intended hole. Use a high pressure lubricant on the needle bearings and shaft and avoid washing the roller tips too much (if at all – you might just wipe them down) because there’s not a good way to reintroduce lube if you manage to wash it all out during cleaning.

If you have studs that mount anything, always check that the stud is completely seated into its hole so it won’t pull the threads.

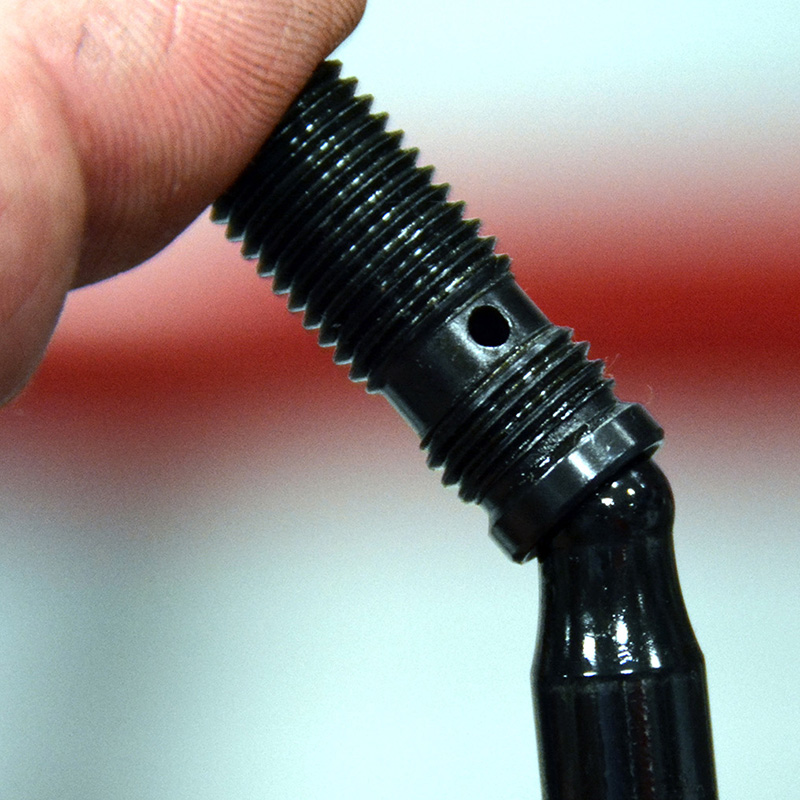

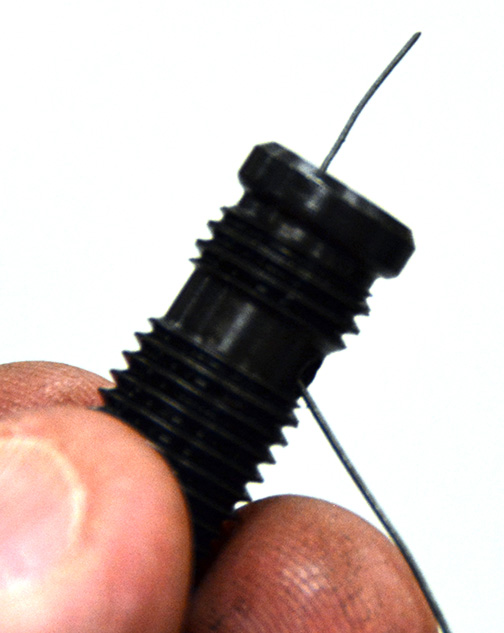

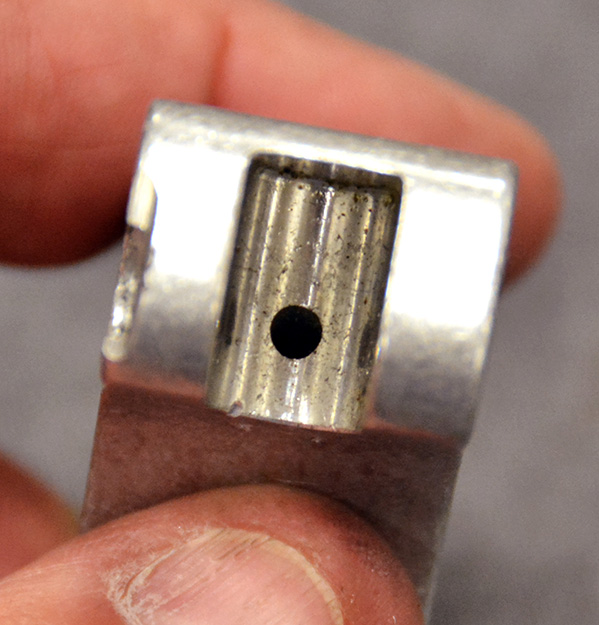

Take all precautions to get the pushrod length exactly right. Too long is an obvious problem, but too short is a problem as well. Every roller rocker I’ve worked with so far has a limit as to how far out you can screw the adjusting bolt that makes up the pushrod cup (or ball end if you’re using a cup-type pushrod.) There are two issues with overextending the adjusting bolt. First, as it extends out it becomes unstable. Most rocker bodies have a counterbore that supports the pushrod cup and once the screw is overextended the sides of the cup can be overstressed without the support of the counterbore. You also need to be aware that on those rockers that oil from the pushrod up through the adjusting bolt and into the main body and then out onto the nose wheel, you’ve only got one and a half to three turns of total adjustment before the oil feel holes drilled in the adjuster are closed off by the rocker body! That’s right, 1½ to 3 turns, that’s it. At .040 in. per turn on a 24-pitch thread, you’ve got to hit the pushrod length on the nose. If you miss the length and over-adjust the cup screw, you won’t oil the trunnion bearings or the nose wheel bearing and your rocker life expectancy will be nil.

During installation, roll the engine over as needed to assemble the axles to the stands without drawing them down against spring pressure. Watch the pushrod and make sure it’s in the cup – if it snaps out of the cup it can damage the rocker. Adjust the valves using the “exhaust just cracked –intake half shut†method. Adjust the exhaust when the intake is half closed on the return trip to the seat and adjust the intake when the exhaust is just coming open off its seat. If you’re running aluminum heads and the engine is cold, subtract .005-.006 in. from your hot specification and check it when it’s hot to get your actual cold specification. Torque the nut on the adjusting screw to 20-22 lbs. ft. for most applications.

Titanium Warning

You’re looking at a full set of T and D rocker arms with stands, trunnion axles, and rockers. You can see that there are three distinct rocker forms here. One for exhaust and two for intake. For specialty heads, you’ll need clearance to get the pushrod past either the intake port or the intake manifold, so running offsets like this is not uncommon. High-offset rockers and offset lifters if used present some side loading and geometry challenges.

If you’re like a lot of racers, you’ve spent the money for copper beryllium seats and titanium valves. You can NEVER run steel on titanium or uncoated titanium against uncoated titanium! Titanium will gall up in a New York second if it runs on itself or on steel, I don’t care if the valve end of the rocker is rollerized or not. If the valve doesn’t have a steel insert in it you must run lash caps. I recently ran into a case where the lash caps were left off of an engine and within sixty miles the roller rocker ate its way through the valve end, through the titanium retainer and dropped the valve into the cylinder on a guy’s hot street machine. All that metal in the oil? AND a dropped valve? That’ll leave you broke.

You Need These

There are too many advantages to roller rockers to not run them. While the initial outlay might be off-putting, they are all rebuildable and the power and reliability gains are well worth it. Just remember, read the instructions for your set and call the technical hot line if you have any questions at all when you first order them or set them up. If you’re running a blower or nitrous or sky-high spring pressures, you might need the strength of heavy duty steel options, so talk to the tech people for advice.

We’re using a pair of Buxton valve spring compressors on this Profiler head, but what I wanted to show you was the stands with the axle mounting studs sticking up. Make sure you check that the studs are seated before installing the rocker, finger tight is good enough.

Depending on the oil map, you’re either lubricating the ball of the pushrod or feeding oil to the shaft. Either way, you’ve only got 2¼ turns on this Comp rocker before it shuts this channel off.

The T and D rocker uses a solid wheel and a solid axle, as do most rocker builders out there. Dan Jesel is the only company I’ve found that offers a fully-rollerized rocker arm with needle bearings at both the pivot and the nose wheel. I’m not saying that there are no other companies that offer them. There may be, and I just haven’t run into them. Jesel is, in my opinion, the best there is and he probably supplies the majority of the professionals out there with rocker and timing belt systems. Beautiful workmanship, and, yes, you will pay for it. But it’s like engine parts art – almost too pretty to run.

On some shaft systems that are oil fed up from the head there will be a couple of special fasteners that are location specific because they are machined to reduced diameters to allow oil to flow up along them and into the shaft. Putting the wrong bolt or stud in the wrong hole will reduce or cut off the oil to the top end.

This preset torque wrench clicks over at 20 lb. ft., and the head has several replaceable bushings to support the T-headed Allen wrenches in various sizes. The tools accepts a 3/8-in. drive socket so you can switch between different lock nut sizes.

The adjuster bolt on a T and D will only move out about three threads before is shuts the oil flow off to the body. The Comp shuts off at about 2¼ turns, and some Jesels shut off at 1½ turns out. Make sure you read the directions, move the adjuster bolt in and out, and confirm for yourself where the oil gets shut off because without oil flow into the main body there’s no lubrication for the bearings, nose wheel, or valve springs.

Here we see just how deep the counterbore is that supports the pushrod cup. With a lot of lift, the pushrod angle drives the pushrod into the side of that shallow cup. Not only is oil shut off if you overextend the adjuster bolt, you’ll lose the support of the body and risk a cup or pushrod failure.

Here’s an example of an old-school Oldsmobile rocker and stand. It’s metal-to-metal at the stand and on the nose where it wipes across the valve stem. I’m old enough to remember replacing a bunch of these due to wear.

This is an example of what NOT to do. This cup-style pushrod was incorrectly sized and was too long for the application. The builder just backed off the adjuster bolt until the top of the cup bored into the aluminum rocker body. Good support I guess, just not what you want to see. Makes you wonder where all that aluminum ended up, doesn’t it?

0 Comments