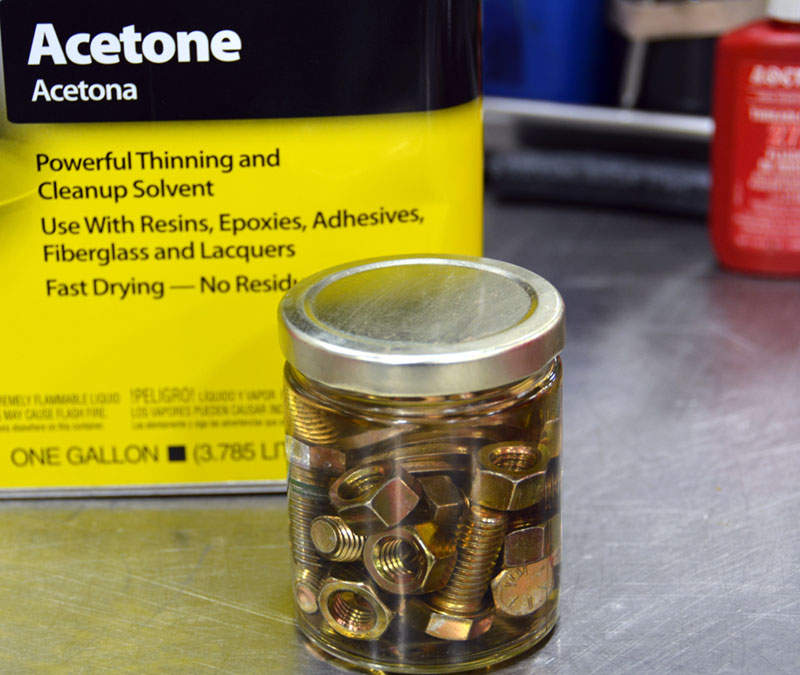

Working on an engine, transmission or differential or other oily part means a little more preparation when you’re applying a threadlocker. The best solvent I’ve found is acetone, although I’ve also used an alcohol based brake cleaner that seems to work well. Bottom line is that all threads have to be clean and dry for the product to work well. I know acetone works… that’s why I use it now exclusively.

I started out on this project with high hopes… I figured I’d gather up a half dozen or so of the popular threadlocker compounds and test them primed and unprimed by setting up an experiment in the shop and then test the results to see what I could determine about how well they set up and what I might expect to see for breakaway torque on similar bolts and nuts. Using a washer as the clamped piece, with all parts cleaned and prepped the same way and with all fasteners made from the same materials with the same plating I set up a few tests using the products I usually stock and began the search to buy a few products that I don’t normally use. Then reality set in…

It Must Be Unobtainium

I discovered that for some reason a number of the products I wanted to test are either not available in the United States, or not available in any reasonable time frame. In fact, some products are available only in Europe. I don’t know why… yet… but I’ll find out. In the meantime, what started out as a feature is going to be reduced to a tech minute while I make a few more calls and research the issue of product availability a bit more so I can get an answer for you. It’s not what I intended, but I still got some interesting results that I can share with you and as I’m able to put hands on product I’ll write about this again in the future.

It’s the Same Only Different

All of the threadlockers I’ve found so far use very similar chemistry. All are some form of an acrylic and contain Methacrylate or di-methacrylate ester and all are anaerobic, curing in the absence of oxygen. Anaerobic is something that occurs or proceeds or even lives without the presence of oxygen. Yes, even lives without oxygen… there are anaerobic bacteria and they are nasty, smelly little varmints.

I’ve worked in some shops where as the drains slowly accumulate the dirt and grease off the cars over the period of six months or a year anaerobic bacteria begin to take hold below the muck layer in the drain troughs and when clean out time comes it creates quite a nasty stench in the shop when you break open the top of their “house†under the muck. Let’s just say having the doors up that day will be to your benefit…

The opposite of anaerobic is aerobic, that that lives or proceeds in the presence of oxygen. There are several ways for glues and adhesives to cure. Some require oxygen to harden, some require water vapor or a certain level of humidity, some are two-part, needing a chemical partner to set up and some cure when no oxygen is present, like virtually all of the anaerobic threadlocker products we’ll review here.

Why Use it at All?

There are a number of real advantages offered by threadlocking compounds. Threaded fasteners are subject to any one of a number of failure modes including mechanical failure due to overload, vibration, tension release or relaxation or a tendency to self-loosen under some operating conditions.

There are a lot of ways to mitigate these failures; we can select much better fasteners, in higher grades or larger sizes for those places where they can be fit and we can safety wire or use locking hardware like split or serrated lock washers or nylon or distorted body jam nuts to increase the torque needed to back off the fastener but mechanical locking systems don’t perform well in terms of controlling the self-loosening associated with lateral or sliding motion between bolted components.

The use of a threadlocker eliminates the extra length of fastener needed to accommodate a washer or taller locking nut, reduces parts count and costs associated with additional hardware and it has several other benefits as well. Since it has some body to it, it fills the void between threads and increases total contact area between the threads basically creating a chemical/resin bond in 100% of the threaded portions where with mechanical locking controls the contact surface areas can sometimes be as low as 15-20% between bare threaded surfaces.

Threadlockers also seals the interface, keeping corrosion due to moisture, fluids or chemicals out of the threads and all the hardware secured by threadlockers is reusable if cleaned, unlike some lock nuts or lock washers. Acetone or MEK (methyl ethyl ketone) renews the surface and prepares the bolt for reuse. Finally, using a threadlocker provides a lubricating factor that makes achieving repeatable torque values easier on threaded assemblies.

I couldn’t get several of the products I wanted to get in time for this feature. I’ve literally been waiting almost two months for some to arrive. I tried to order Loctite 276 but for reasons that are unclear it seems to only be available in England, so I located an MRO product that is similar. Not sure what the shipping will be, but I’d like to try the 276 because it’s actually listed as a medium viscosity threadlocker whereas the MRO product is a retainer product, so I’m not sure how they compare. One product came in expired… one of the activators… and another is due to arrive later this week. My advice is make sure you get your products ordered in the off season because it appears the market dries up pretty quickly once racing season lights off!

Product Overload

There are far more threadlockers, bearing and sleeve mounting products and other retaining and sealing compounds out there than I ever suspected. For our racing applications the primary concerns are strength and temperature range and there are several options for temperature range within each strength range.

Strengths range from very low to very high and temperature resistance ranges from about 250 degrees to upwards of 400 degrees. The largest and best known maker of these products has got to be Loctite… a name so well known that most products used to secure or glue fasteners are known generically by that name, even if made by other companies. To my knowledge there are only three companies I can find but that’s not to say there aren’t a lot more out there. MRO Solutions is one I found at an industrial supply company, and Henkel makes Loctite and Permatex markets threadlockers as well. I’m sure there are others I just am not aware of.

Strengths, Temps and Application

From low strength to high the colors of Loctite products run purple, blue, red or red-orange and green. In each color and strength of product there is typically one or more temperature ranges for each color that will be designated by the same color but with a different product number.

As a general rule of thumb the color you use will be partly dependent on the fastener size it’s applied to. For fasteners under a quarter of an inch the purple formulation is recommended, for fasteners up to three-quarters of an inch the blue product is your first choice and over three-quarters of an inch the reds are recommended, although these are only recommendations. I have used red 272 on 5-16†and 3/8†fasteners successfully when I wanted to be absolutely sure the fastener wouldn’t loosen on some critical applications. I’m equally certain it was overkill.

The greens are used for large assemblies where disassembly is rarely required and remember than any of the high strength formulas in either red or green may require heat to facilitate disassembly. Heating a thread locked joint to over 300 degrees or so with a heat gun will greatly ease disassembly if you need to get the nut off or the bolt back out.

Under each color there are different temperature ranges of products with different holding characteristics formulated to specifically combat things like vibration or contamination. There are even specific formulas for oiled or re-oiled fasteners or fasteners subject to extreme vibration or lateral force. There are several online publications and application guides for you to access and review and I strongly suggest that you do a little reading on the subject… there’s a lot to learn that will help you in your racing program.

The type of metal and the plating used affects threadlocker performance. Inactive metals like titanium, stainless steel, zinc plating, magnesium, black oxide or anodized aluminum may require the use of a primer and activator… especially if BOTH bolt and threaded hole are made from an inactive material. If only one of two surfaces is inactive you can get away with not using a primer and activator, but when in doubt use the appropriate cleaner-primer and activator to make sure the joint is secured as designed.

This is how I laid out the first test and I was pretty disappointed and confused by the results. There appeared to be no benefit to using the Loctite primer over just using acetone only. Reading the product label on the primer can suggests that it’s mostly acetone anyway, so you might be able to save yourself the money of buying it. The most disturbing aspect of this first test was that I literally had no product work correctly other than the green wicking 290. I didn’t know what to expect with the gasket maker, but it really didn’t act like it provided any extra resistance to removal, which also confused me because I’ve used it on block drains and oil gallery plugs and it seemed like it locked those tapered pipe fittings in pretty tightly. Maybe I’m just tightening them more than I think. As it turns out the reason that I got such sketchy results is because I just didn’t apply the product correctly!

You Can’t Just Slap it On

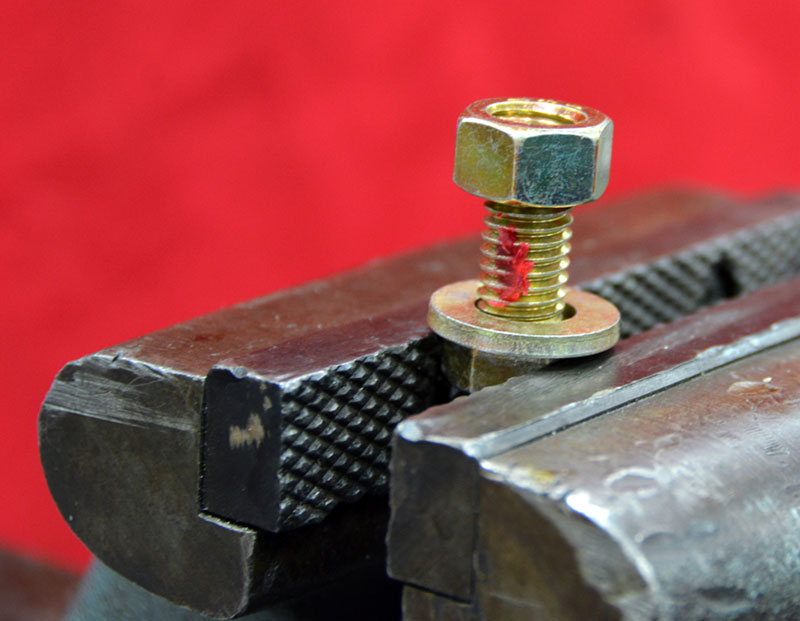

How you install a threadlocker is critical to making it work correctly for you. If the product is only applied to the bolt air pressure below the bolt may force the product out of the threads as the bolt is run in and the joint will fail. The entire area between the nut and bolt or bolt and hole must be wetted for the product to work as designed. Any excess threadlocker can be wiped away after installation so more is better.

I found this out the hard way… and in learning this lesson I discovered that I have been using the product wrong for years! Using a small amount of product doesn’t create the anaerobic environment you need to make the product cure… as you will soon see.

You can’t just have one bottle of product and use less of it on a fastener to achieve a lower level of adhesion. I’ve often used red 272 on most of the fasteners I was chemically securing… putting just a drop in place on the smaller fasteners and more on the larger ones thinking that using a small amount would result in less breakaway torque on the smaller fastener while still providing sufficient holding power. Silly me! I was wrong and the testing I’ve gotten done to this point proves it. The correct way to apply a threadlocker is to make sure that all the engaged threads, male and female, are fully wetted with the product. If you need less hold, pick a product with less hold, but always wet the threads the same way.

The Experiments

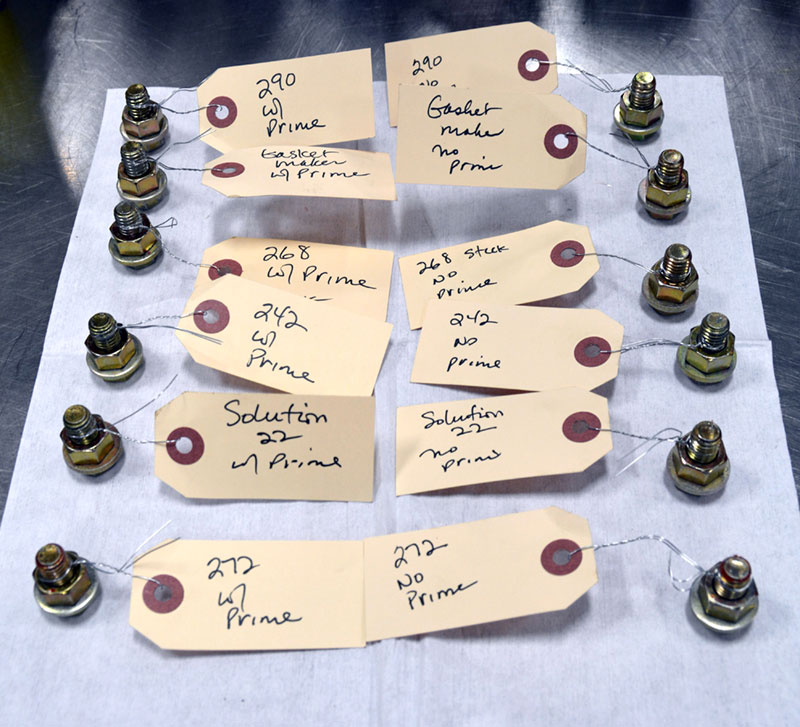

I started out using exactly the same bolt, nut and washer for each mockup… an inch long anodized grade eight 7/16 coarse bolt and nut and I put an 1/8†grade eight extra thick washer between the nut and bolt and torqued the assembly up to 40 foot-pounds. This was done after washing the new hardware up in acetone. The first go-around I just did my normal routine and put about two heavy drops inside the nut and a single stripe of the solid adhesive on the bolt, as you can see in the photos accompanying this article. I set them out on my workbench and went back to work.

The next day, twenty five hours later, I grabbed my Snap-On Torque-meter with tell-tale and loosened them all back up. My control part, assembled clean and dry and torqued to 40 foot-pounds broke away at 34 foot pounds. And so did every other assembled bolt in the test with the exception of the one secured with green 290 wicking Loctite, which took about 52 foot pounds to loosen. All the rest came loose somewhere around 33-37 foot pounds. To say I was confused was an understatement. I walked away from the mess and gave it a little thought and did a little more reading, and lo and behold I stumbled on the answer. The only product that I applied properly was the 290! In every other case I used too little and failed to create an airless environment over a large enough area to allow the adhesive to cure properly.

I washed up the hardware, removed all of the adhesive previously applied and repeated my experiment, this time making sure that I had sufficient product applied to fully wet all the male and the female threads that were engaged with the nut fully torqued.

This time, the MRO Solution 22 green retaining compound, which previously released at 37 foot-pounds, took 77 foot-pounds to break away. The Loctite 272 which released at 34 foot pounds in my failed experiment took 66 foot-pounds and the Loctite red stick number 268 went from 33 to 53 foot-pounds in the second test.

I’ve ordered (and have yet to receive) a couple of different types of primers along with another type of threadlocker, but I’m out of time to get this out, so I’ll have to do a little more work and follow up with another short piece on what else I’ll learn once the products arrive. I’ve always discounted the medium strength blue 242 but I think I’ll experiment with that formula a bit more and see if perhaps it’s been me creating the problem and not the product. I might even order up some purple and see how that does… you never know!

Things to Remember and Takeaways

Here’s what you need to remember about using threadlockers. One, make sure you get all your hardware cleaned up with acetone or MEK before application unless you’ve got a product designed to work with oily surfaces in your tool kit (Loctite 266 is just one out there.) Two, check your dates on your products, some have expiration dates and they may not work well if they are too old. Three, use enough… too little doesn’t work at all and you’re wasting time and money… and potentially putting your assembly at risk by doing it wrong. Four, if you are applying the products to inactive materials the application technique changes. You must use an activator… which is different than a cleaner-primer… to have it secure the fastener. The product works by grabbing hold of the tiny peaks and valley of the threads and some plating’s or materials are slick at the microscopic level. Five, use the right product for the right application. There are thread lockers, gap filling, retaining products and glues and adhesives out there under the Loctite and Permatex brand names and it’s easy to mismatch the product to the application. Application guides are online… find them and read them, there’s no point in having a failure over not taking the time to learn how to use the materials.

Until next time, may every pass be your best pass…

0 Comments