Sensing the unseen, balancing the forces, holding the course

Grabbing for traction when there isn’t much to grab.

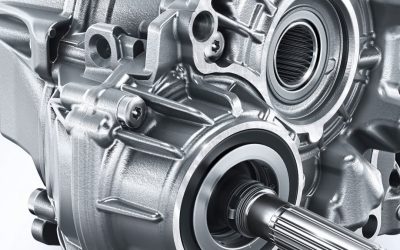

The unique components for ESP include a yaw sensor, a lateral acceleration sensor and a steering wheel angle sensor. The system shares the wheelspeed sensors as well as hydraulic and electrical control units with ASR and ABS. But the entire ESP traction control encompasses the entire car.

Shazam in a séance! The marketing acronym for this Mercedes-Benz traction-control system puns against the once-fashionable notion of ‘extra-sensory perception,’ a collection of now-discredited delusions of semi-magical knowledge (‘parapsychology’ and its related pseudo-sciences). On Mercedes-Benz cars, however, ESP refers to the Electronic Stability Program, standard to begin with on 12-cylinder cars, optional on 8-cylinders and later on others, available perhaps on most Benz car models eventually. The system is ‘extra-sensory’ only in the removed (but entirely accurate) meaning that it has additional – that is to say, extra – sensors and microprocessors, extra components other traction control systems don’t. Its functional operation, however, certainly does seem magical – until we remember Arthur C. Clarke’s observation (he wrote 2001, A Space Odyssey) that every technological advance seems like magic, until later, once we understand how it works. Or you may recall the scene in The Wizard of Oz… “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!†The Wizard’s Emerald-City hocus-pocus evaporated completely, the moment the Yellow-brick-roaders saw inside the contraptions of his wizardry.

Well, here at StarTuned, we want to pull back all the curtains, so you can watch all the ‘little-men-within-the-machinery,’ busy at their digital and hydraulic work. We want to replace the illusion of magic traction in Mercedes-Benz’ ESP with a clear understanding of the system’s strategy and tactics, of its interrelated sensors, of its control units and actuators. This issue, we’ll cover the overall system and its sensors, along with a few interesting oddments. Next time, we’ll talk about the actuators, review some diagnostic procedures and conduct several thought-experiments.

More practically, of course, we also want to explain how to repair the ESP system should you find problems. Your customers may suppose you’re a mechanical mystic or a digital dervish, but you’ll know better. With ESP as with all serious automotive work, you must solve and correct real, objective problems – not fanciful, imaginary ones. There may be vehicular hypochondria on the part of some motorists, but there’s no placebo-effect with the machine, itself, so a car requires a knowledgeable mechanic and not a prestidigital marketing magician. And development of that objective technical knowledge, of course, has been our objective since our first issue.

ESP Underway

ESP Underway

While the system relies on very rapid hydraulic/mechanical and near-instantaneous electrical functions rather than on occult powers, if you push the car to its traction limits, it certainly does seem mysterious, the way the system retains or recovers control under circumstances where all your previous driving says you’ll lose it and slide or spin.

I tested a Mercedes-Benz with ESP on an empty parking lot in a snowy New England harbor, erratically mottled with blobs of partially frozen but still very slippery seaweed from an unusually high winter tide. An ocean-churning Nor’easter had uprooted the stuff from the seafloor the day before, and the high water left little slimy tufts stranded around the salt-damp blacktop. Then the snow fell, making a perfect erratic surface for a traction-test. A buttered glass road with scattered handfuls of marbles could not have been more unpredictably slippery.

After accelerating, braking and cranking the steering wheel from right bump stop to left and back, I had to spin the test car through a 180 using only the parking brake. Could there be something peculiar in the tires, in the seaweed or on the snowy asphalt to make the wheels follow the intended track so closely? I knew how ABS controls a braking stop and how ASR keeps the drivewheels from spinning under acceleration, but even understanding those systems, I was astonished how effectively ESP kept the vehicle on course in the erratic poor traction.

The car shuddered and shivered as I spun the wheel right and left. But it went where I aimed– not perfectly smoothly, not any more than a full-pedal ABS emergency stop is perfectly smooth – but it always held the course I chose, up to the very edges of traction, even through the intermittent slimy globs of beached seaweed. Just as ABS and ASR pulse brakes off, ESP pulses specific brakes on, to control steering.

You probably recall how impressive it was the first time you pushed a vehicle’s brakes into an ABS-brake pulse or floored an ASR throttle on an uneven, slippery roadway. In the absence of an empty, snowy, slippery parking lot, it’s harder to test the ESP system. But if you get the chance, you’ll find ESP’s traction control in turns is as surprising, and as enlightening, as your first ABS-pulsed stop. We learn things, I guess, through the seat of our pants as well as through the top of our heads. But working here with words and pictures on flat paper, we must take the second course.

What Does ESP Do?

ESP boasts a long pedigree from earlier Mercedes-Benz traction-control systems. ABS sets out to prevent skids and slips from a driver’s excessive pressure on the brake pedal for the available traction, ASR from a driver’s excessive pressure on the accelerator under similar conditions. ESP expands that objective to include slips and skids when a driver turns the steering wheel beyond what ordinary traction allows in the circumstances.

The parking-brake spin resolved my ‘what’s-up-their-sleeve?’ suspicions of traction tricks, but the amazing part was the actual ESP operation, itself. Just as ABS pulses individual brake caliper pressures down or off to prevent lockup during slowdown, just as ASR feathers the throttle, spark and individual drivewheel brakes to prevent drivewheel spin during acceleration, ESP applies individual wheel brakes to prevent sideslip in a turn. It applies a brake on the axle that is not slipping, to correct the car’s yaw resulting from the axle that is.

‘Engage the Caterpillar’

‘Engage the Caterpillar’

It’s somehow perversely fascinating that a very subtle, complex system like ESP includes something amazingly simple and direct at its functional core. Rowboats, bulldozers and sidepaddle steamboats steer by directly acting on the rotation of the vehicle. Want to turn your bulldozer right? Stop the right track, and the ’dozer pivots right. Turn your rowboat by pulling on one oar as you push on the other. Ditto with your sidepaddles on a Mississippi River steamboat.

Ever operate a bulldozer? Know how to throw one into a turn? Or have you at least watched the tracked action? None of the alignment complications of caster, camber, toe or SAI. No concerns about toe-out in turns or suspension travel. The ’dozer just moves one track faster than the other and pivots – it yaws – toward the slower side, grinding the dirt beneath. Nothing complex or subtle about it.

In principle, that’s what ESP does. If one axle starts to slip to the outside of a turn, the system applies a brake on the other axle to pivot the car’s centerline back parallel with the direction of travel. How the system does this is a good deal less simple than how the output works, but the basic function is just as simple as that. We’ll get to the non-simplicities shortly.

Right away, of course, the complications begin. First, on the ESP car, there’s not one ‘axle-bulldozer,’ but two, one in the front and one in the rear. Activate the correct brake, and you correct the slip, but the system has to know which one to apply. Activate the wrong one, and you improve nothing, because the wheels on that axle were already sliding.

Understeer and Oversteer

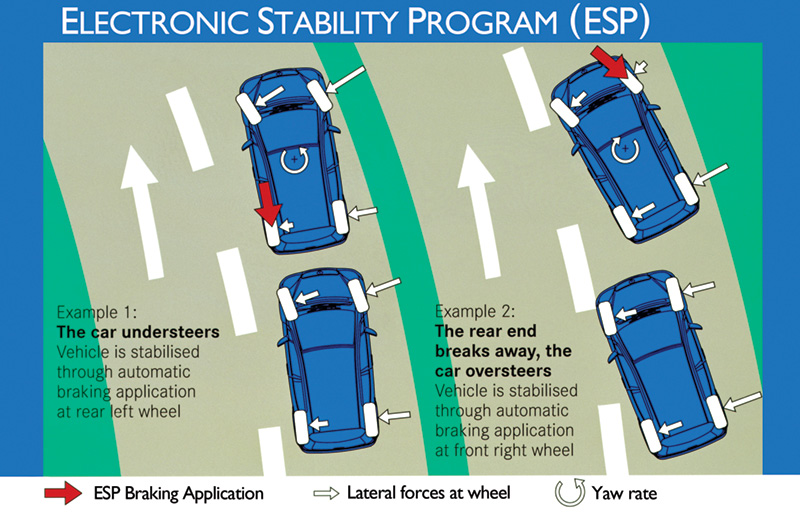

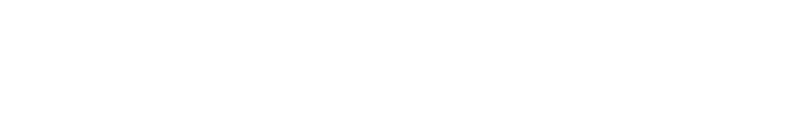

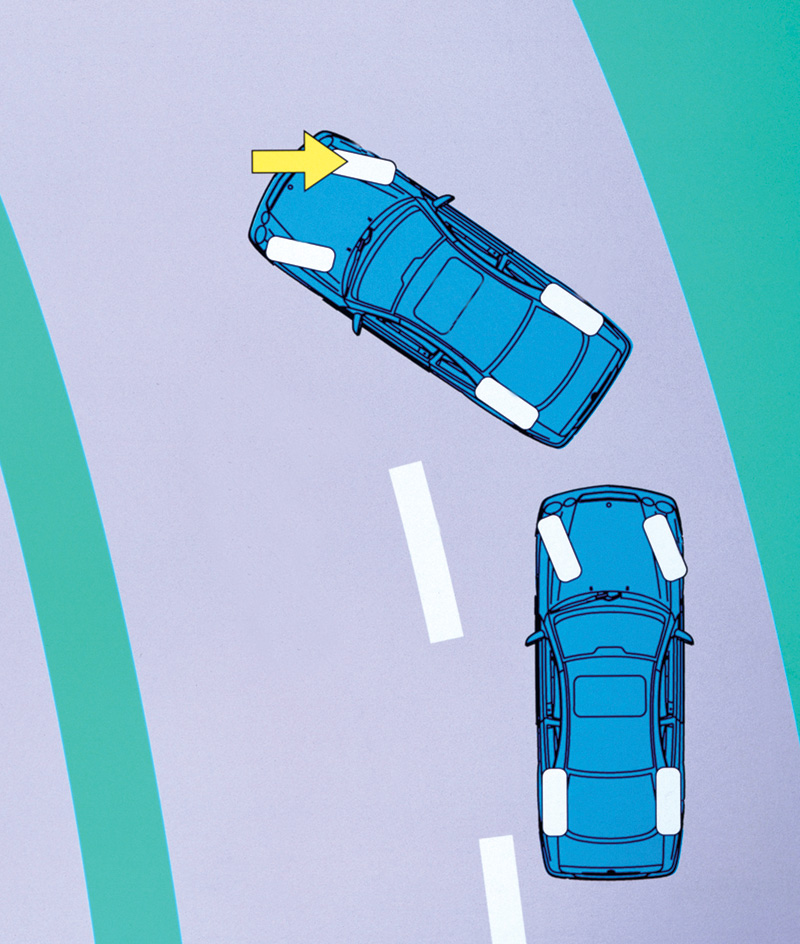

How do you control wheel sideslip at one axle? With a single brake on the other axle, the one that’s not slipping. This requires instantaneous data interpretation and brake actuation by the system. If the front wheels start to slip toward the outside of the turn, ESP activates the inside rear brake to yaw the car back into the correct direction. If the rears are the first to slip, the system applies the outside front wheel brake instead, for the same yaw correction. This graphic is perhaps misleading in one respect: Once sideslip begins, the sideforce at that axle reduces substantially. We should consider the sideforce arrows as flagging the force that was there a split-second before.

Hold a car in a constant-radius turn and increase the speed around the circle, and eventually one of three things occurs: If there’s enough traction (or if the center of gravity were high enough), the car rolls over. If there’s more traction at the rear wheels than at the fronts, the front tires can start to slide outward, and the curve opens its radius up. This is usually called “understeer.†If there’s more traction at the fronts than at the rears, the rears can slide outward, the curve suddenly tightens, and the car can spin around sideways or even backwards. That’s called “oversteer.†NASCAR fans, their conversations speaking from the traditions of oval-track racing, with the car frequently on the edge of lateral traction, favor calling the first “push†and the latter “pull.â€

Since traction could never be exactly equal on each axle (or exactly proportionate to the load), every car must either oversteer or understeer. Which axle will lose lateral traction first? There’s no way to tell across the board, of course, but for safety and by design most cars understeer rather than oversteer. Understeer is self-limiting in the sense that, once the front wheels start to slide outboard in a turn, the turn becomes less steep, the centrifugal force declines and with it the sideforce. Of course, there might be an immovable obstacle or a steep hillside on the side of the road, so stability is not an end in itself. It’s also much easier for most drivers to recover from understeer by a combination of slowing and tightening the steering wheel angle.

Oversteer is self-worsening. Once the rear wheels start to slide outboard in a turn, the turn becomes immediately steeper, and centrifugal force and sideslip increase. The slide gets faster very quickly. It’s much harder to recover from oversteer unless you have quick reactions, experience driving on ice and the presence of mind not to touch the brakes or reduce the throttle when it occurs.

You could make most cars oversteer, I suppose, by piling the trunk full with sacks of concrete or by using worn tires or sagged inflation. But under normal circumstances, most cars lose front wheel traction first, and nose to the right off the road or left across the lanes, depending on the direction of the turn.

Why have ESP? For just such roads as this, circling through and around steep mountaintops, in and out of sunlight, under traction conditions that change abruptly and often. A system that improves traction use on such challenging roads means a substantial margin of safety for ordinary roads.

Roman Roads

Why design and build such a complex system as ESP? Part of the reason is that accident avoidance is a kind of automotive grail the best vehicle engineers pursue. Part of the motivation comes from the most extreme roads in Europe. Most of us in the USA live where the world really is flat, where most of our roads are north-south or east-west, with gentle curves where needed. When we have mountains, the roads are steeper, but still designed for the traffic speeds we expect. Most of Germany is as flat as Michigan, with hills, small outcroppings like the Harz Mountains and some large river valleys here and there. But south lie the Alps, and any German car must be able to drive through the Alps in safety and under control.

The Alps are somewhat higher than the Rockies, but what makes them unique is the dramatic height difference from peak to valley, a consequence of the particularly hard, crystalline rock and the specific erosion, mostly by glacier rather than by rain or wind. Glaciers excavate a valley floor deeper but have no effect on high peaks. What this means is that the Alps are very steep. On a trip to Germany, driving south from the Black Forest, I thought, ‘What a wide, incredibly sharp-edged storm is coming.’ As I drove closer, I saw more clearly. It wasn’t a cloud; it was stone, covered with permanent snow in August. The ‘storm’ was the north face of the Alps.

Roman roadbuilders built straight, flat roads, like the Via Appia here, wherever they wanted across the warm and graceful plains of Italy. But inflexible geology determined where they built roads through the Alps, the same inflexible geology that makes modern roads follow the Roman routes.

Because the Alps are so high, so steep and so cold, the roads through them are difficult to drive. Rain, fog, glare ice and snow can occur in rapid succession on any day of the year. Traction can be perfect where the pavement is in the bright sun and nonexistent once you drive behind the shadow of a rise.

The Romans laid out the major roads over two millennia ago, and they didn’t concern themselves with banking turns or highway safety. No road was too steep or too narrow as long as two long columns of armed men could walk it at a thousand paces an hour. A glance over the precipice was enough to encourage the legionnaires to stay away from the edge. What the Romans wanted from a road was structural stability: They paved the road using huge buried stones, too heavy for the locals to pry up and vandalize whenever the Romans turned their backs.

No speed limits here, and no need for any. In the very center of Western Europe are roads nobody speeds on twice. Even with the most advanced traction controls, a driver is apt to sit up a little straighter and drive with increased attention around these curves.

We think of roads as avenues of travel and commerce; the Romans thought of them in military terms. If the Germanic colonial subjects on the far side of the Alps got restless under the various exactions imposed and looked likely to start a dustup, those indestructible roads meant the Roman Army could be anywhere in the Empire within about two weeks, to lend their muscular powers of persuasion to the feebler eloquence of the tax collectors.

That’s all ancient history, literally, but many of the Roman roads through the Alps are still there. Not usually the original Roman pavement, of course, but their routes and roadmaps. The mountains, you see, stayed put, and our roadbuilders can no more ignore them than the Romans could. Not only would it be impractical and uneconomic to re-route most roads, in most cases there aren’t alternative routes anyway, without blasting impossibly expensive long tunnels.

Some of the Transalpine roads may technically be unlimited-speed Autobahns (or the Austrian, Swiss, French or Italian equivalents), but the hairpin turns, steep slopes and near-constant ice provide a speed enforcement that issues no warning tickets. Go over the barrier on some of these roads, and it won’t matter whether you wore your seatbelt or have airbags in your car. An ejection seat and parachute might help, but they’re not in the accessory catalog.

Electronic Slide Perception – Sensors

So that’s how the system uses the bulldozer princ- ple to nudge the car back into the path of the curve. But how does it know sideslip has begun? And how can it tell which axle is slipping, so it can activate the correct brake on the other axle?

There’s no ‘sideslip sensor,’ you see, never mind one for each axle. The system has to quickly infer sideslip from the incoming sensor information. Of course, there’s no braking-skid or acceleration-spin sensor for ABS and ASR, either. In each case, the computer infers the traction loss by comparing input sensor data with its stored, read-only memory parameters to distinguish circumstances incompatible with continued traction. But that comparison is much more complex with ESP. Here’s our best understanding of what goes on.

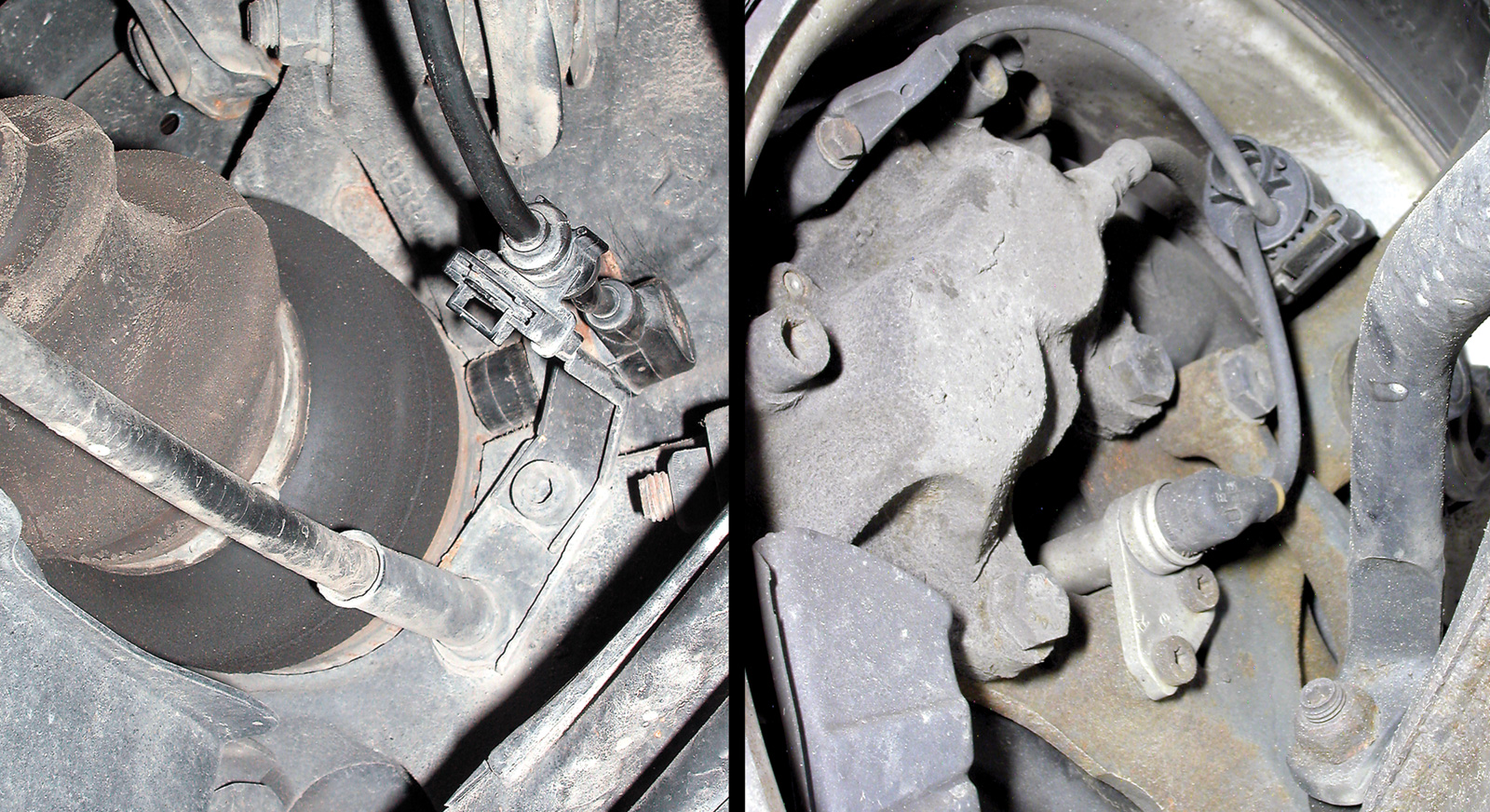

All of the intertwined traction controls, from ABS, through ASR to ESP, depend critically on the wheelspeed-pulse information from each wheel. These induction sensors provide the fundamental data on vehicle speed and on variations at each wheel. If a single one of them stops working, the whole interconnected set of traction-control systems turns off; the car drives as a normal car without traction control; the warning lights turn on as a DTC takes up residence in memory.

Wheelspeed

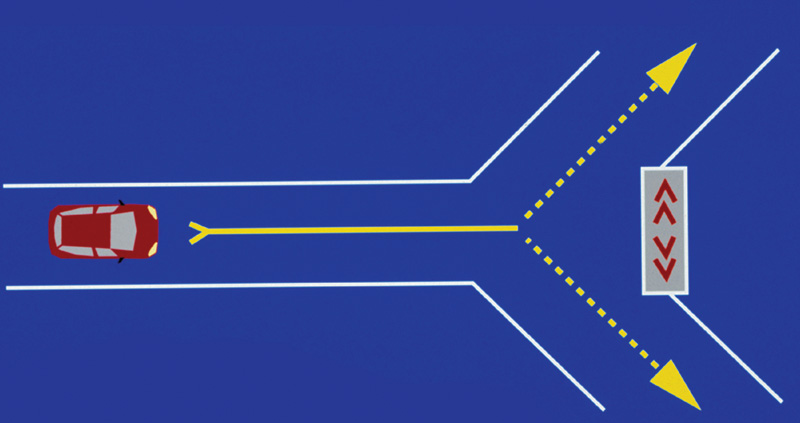

Our old ABS/ASR pals, the wheelspeed sensors, are just as important to ESP as to the earlier traction controls. These sensors function in the same inductive, tooth-counting way we’ve discussed earlier.

The major sensors providing information input are these: the wheelspeed sensors for the vehicle speed, a steering wheel angle sensor for the driver’s directional intentions, a yaw sensor for rotation around the vertical axis and a lateral acceleration sensor for sideforce in the middle of the car. From the wheelspeed and the steering wheel angle, the computer can calculate what the range of the sideforce should be under ideal conditions. The road could tilt one way or the other, however, so this is not yet enough.

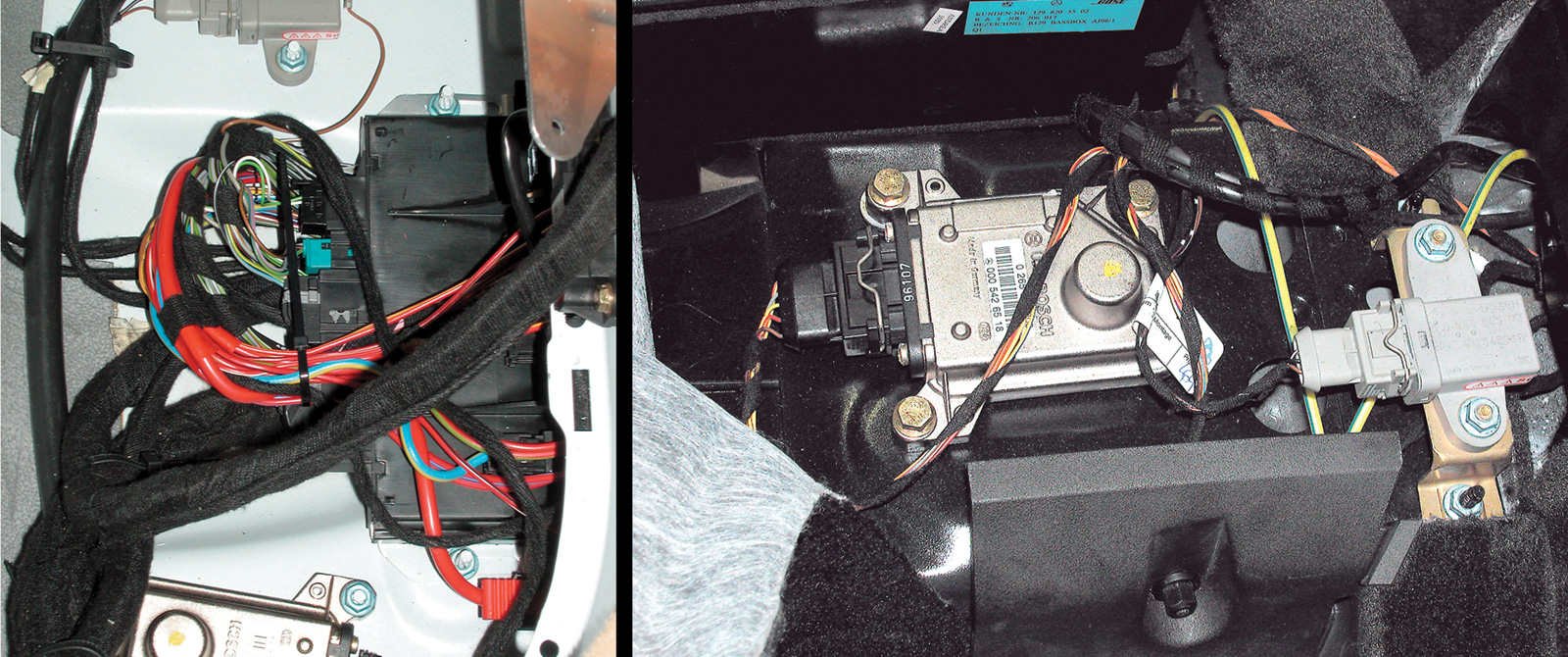

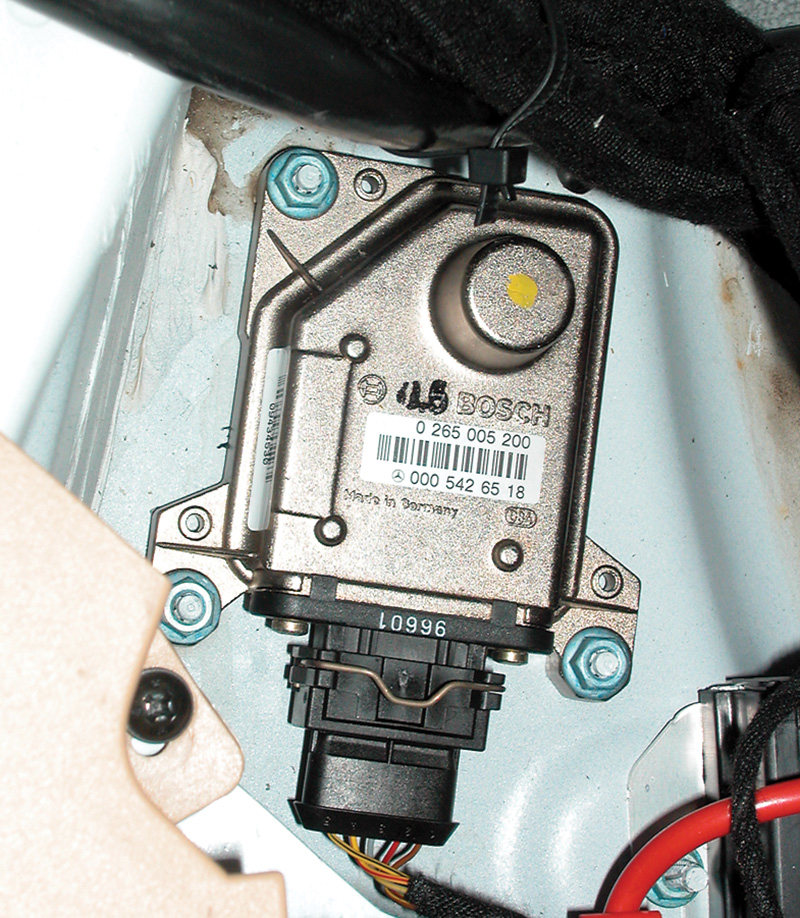

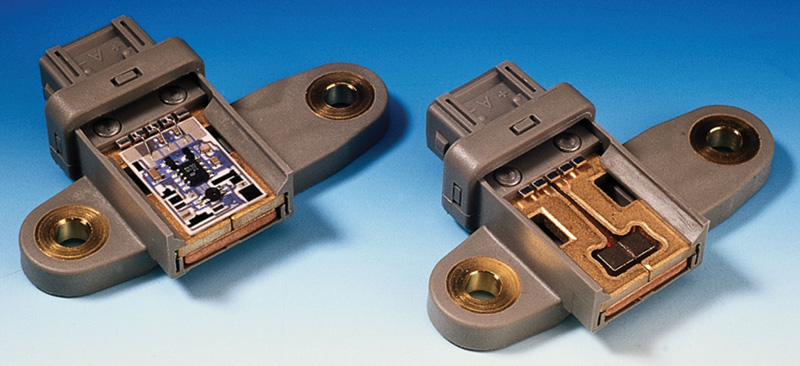

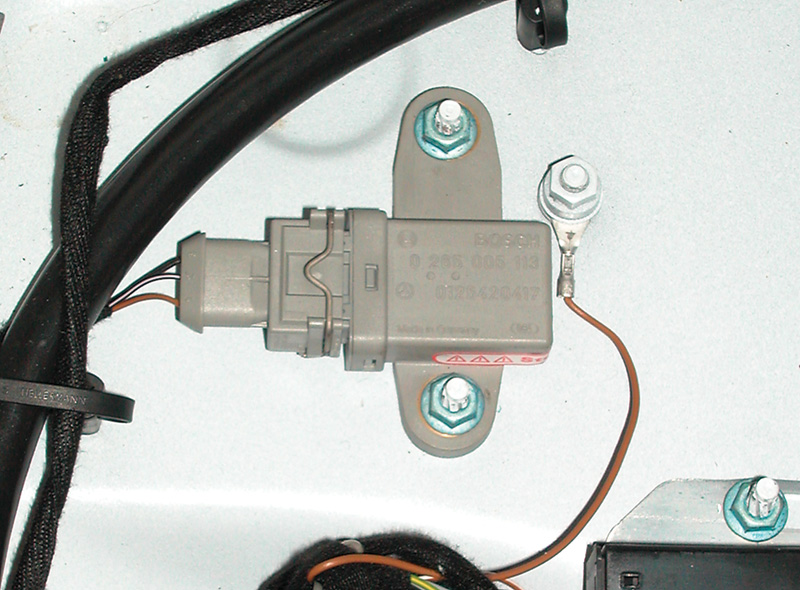

The major sensors unique to ESP are the yaw sensor (shown in cutaway at the beginning of this section) and the lateral acceleration or lateral-G sensor. They are close to one another, but in different places for different models. In most sedans, they’re under the rear seat. In the 129 on the right, they are atop the rear tunnel just below the carpeted covers. Both sensors include internal microprocessors, special-purpose mini-computers, to convert the raw detector signal to an information signal, a very precise voltage, relayed back to the electronic control unit.

Yaw and Direction

Most interesting of the lot is the yaw sensor. This detects rotation of the vehicle around its vertical axis. The sensor works by multiple piezoelectric actuator/sensors responding to the Coriolis effect. Coriolis makes hurricanes and tornados turn counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern. It’s what makes water draining from a sink usually turn in the same direction. When air or water closer to the equator moves toward the North Pole, it will tend to move farther eastward because it was moving faster eastward at its original latitude. Correspondingly, air or water to the north moves westward as it moves south, since it was originally moving more slowly eastward. If you’ve ever tried to walk in a straight line from the outside perimeter of a moving merry-go-round to the center, or vice-versa, you noticed how your path was not only thrown to the outside by centrifugal force, but also ahead of or behind the merry-go-round depending on whether you tried to walk radially inward or outward. Obviously, it also depends on which way the merry-go-round rotates.

Sustaining a continuing standing wave atop a small cylinder in an evacuated chamber, the yaw sensor (also shown in cutaway on page 20) provides accurate information to the control unit about any change of direction the vehicle makes.

Things happen similarly in the yaw sensor of the car. In the earlier, cylindrical-element sensor, there are eight piezoelectric actuator/sensors around the circumference of the top edge of the calibrated cylinder, oscillating in its little evacuated chamber. Every other actuator/sensor, four in all, actively pulses at a precise frequency to introduce a standing ellipsoidal wave along the rim of the cylinder. The alternating four unpulsed actuator/sensors also move in and outward radially in phase with the wave.

As long as the vehicle does not turn, they report no yaw. When the vehicle rotates around its vertical axis, that is, when it turns, the passive actuator/sensors vary slightly in their electrical capacitance, in response to the Coriolis effect, because they also try to move in the direction they were moving in as the turn began. The wave wants to stand still, not rotate, so it imparts some of the rim momentum to the sensor elements. A later, still smaller version of the yaw sensor uses what amounts to two interleaved combs. As the vehicle turns, they shift slightly relative to one another, changing their joint electrical capacitance.

There are, kindly, befuddled teachers in school used to tell me, no stupid questions. Well, OK, but as I learned later in the Automotive School of Hard Knocks, there are still stupid people, people who ask dumb questions, a role that’s often been mine. So I asked an M-B engineer whether they needed a mirror-image yaw sensor for the Southern Hemisphere, where hurricanes and water draining from sinks rotates the other way, clockwise. Nope, he answered, politely stifling a guffaw, it’s the Coriolis effect of the yawing car involved here, not of the rotating planet. Then I remembered, it’s also the Coriolis effect an ice-skater uses to increase the speed of a spin by drawing her arms and legs inward. Her total rotational energy remains the same even though the spin increases, because the average radius of the spun mass is less, but the rotational momentum stays constant.

There are, kindly, befuddled teachers in school used to tell me, no stupid questions. Well, OK, but as I learned later in the Automotive School of Hard Knocks, there are still stupid people, people who ask dumb questions, a role that’s often been mine. So I asked an M-B engineer whether they needed a mirror-image yaw sensor for the Southern Hemisphere, where hurricanes and water draining from sinks rotates the other way, clockwise. Nope, he answered, politely stifling a guffaw, it’s the Coriolis effect of the yawing car involved here, not of the rotating planet. Then I remembered, it’s also the Coriolis effect an ice-skater uses to increase the speed of a spin by drawing her arms and legs inward. Her total rotational energy remains the same even though the spin increases, because the average radius of the spun mass is less, but the rotational momentum stays constant.

This effect on the piezoelectric sensors must be incredibly small and the changes in the electrical signal must be incredibly minute as well. But that’s enough for the electronics housed in the sensor to translate the information into a yaw-rate millivolt signal and send that to the control unit. The yaw sensor can detect and report rotation much slower than once per hour, a most leisurely turn, but a sensitivity affording substantial overcapacity for detecting rotational change.

This information tells the control unit the vehicle’s change of direction. But it needs more pieces of information to determine whether the vehicle is slipping sideways or not: what is the side force and what direction is the driver trying to achieve with the steering wheel? How fast is the vehicle going, from the wheelspeed sensors’ signals? What about the engine speed and torque output, the transmission gear, the brake application status? On to the other sensors….

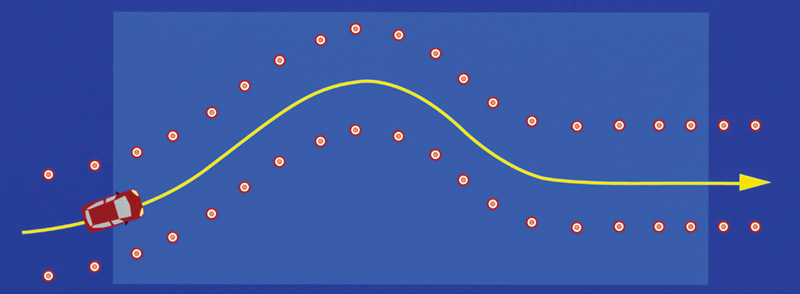

Mounted as close as is practical to the very center of the car, the lateral acceleration sensor detects lateral acceleration and sends quantified information about that in the form of a millivolt signal to the control unit. The sensor itself is Hall-effect, but the internal microprocessor translates the data into a scalable signal.

Sideforce – Lateral G

The lateral acceleration sensor is relatively delicate, about like the bulb in an incandescent troublelight, though it can sustain the bumps and shocks of the moving car. If you remove it for test or replace one, however, be careful not to drop it on the floor or smack it against a workbench or hard parts of the car. The exclamatory red label on it reports (in German) that it’s sensitive to impact damage.

The lateral acceleration sensor uses a pair of minutely swinging weights within a Hall-effect sensor, responding to the lateral G-force the car is under. Even more than the yaw sensor, it must be positioned close to the center of the car. If it were too close to one axle or the other, after all, it could report a false reading if the nearer axle slipped more than the farther or vice-versa.

The sensor has a range of about 1.4 G’s in either direction (more sideforce than tires can usually support), while it is sensitive enough to report the lateral acceleration resulting if you rock the car gently back and forth. We’ll cover how to test this sensor and the other components next issue.

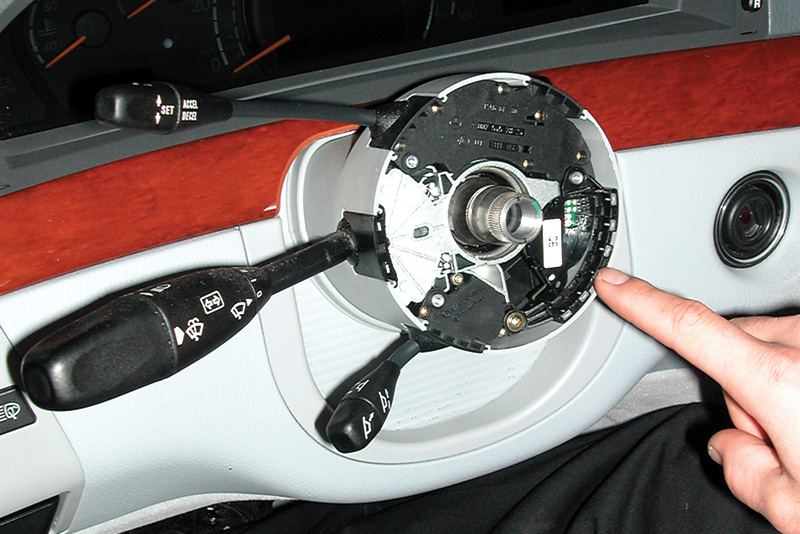

The system not only has to detect sideslip, it also has to factor in what the driver wants the car to do, the direction he wants to steer. Reporting that information is the job of the steering wheel position sensor

Reading the Driver’s Mind

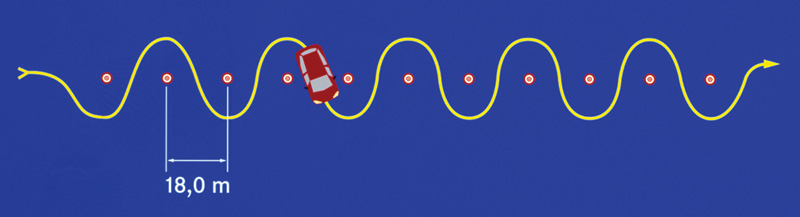

The steering wheel position sensor, the device reporting what direction the driver wants the car to head in (whether possible or not), consists of an array of nine LED’s and light receptors, optical sensors, in other words, separated by a plastic wheel with variously spaced slots. The spacing of both LED’s and slots are so arranged that each position of the steering wheel corresponds to a unique combination of light-sensor communications. This means the control unit can detect exactly where the steering wheel is at all times.

The steering wheel position sensor must be ‘initialized’ anytime it’s ungrounded or replaced. You initialize the sensor by either turning it slowly from lock to lock (engine running) or by driving straight ahead at a speed above 12 mph. This process enables the system to recalibrate the straight-ahead position.

The system also needs information from the engine control system, the transmission controls (to tell what gear it’s in and whether a shift is imminent, and thus what the effect of a throttle change will be on torque at the wheel) and various other sensors, including the ESP-off switch (which actually only turns off ASR engine torque control).

Doing the Fast Math

As mentioned earlier, there is no sideslip sensor. The system has to noodle that out from all the information streaming into the control unit. But we know what information is available and what kinds of traction controls the system can use, so we can understand the intervening steps, at least in principle.

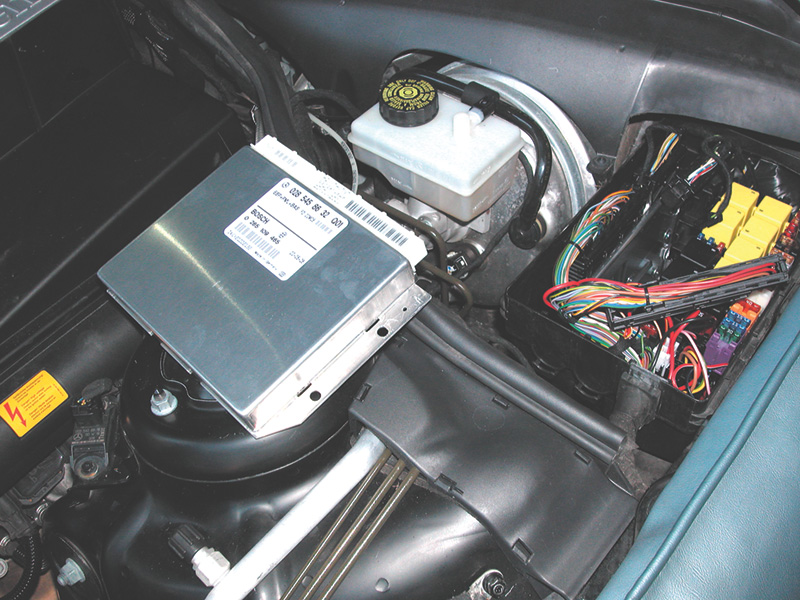

The information from all the sensors we’ve described in detail, as well as data from the engine and transmission controls, flows into the ESP control unit, here unplugged and visible from the side. All the read-only memory for allowable thresholds, all the calculations to determine what the car’s situation is and what steps, if any, to take for correction, as well as the output signals to the traction control actuators, center here.

First, let’s have the problems clear: Longitudinal and transverse slip can be independent. That is, a car may continue in a straight line, parallel to the tire tread, if you lock the wheel with the brakes or spin the drivewheels with engine power. Or the wheels could continue turning at a speed perfectly coinciding with vehicle longitudinal movement (parallel to its centerline), even though one or both axles are sliding sideways and the car is out of control. The control unit must necessarily infer the need for traction control, and what measure to take.

There are several hard inference problems here: How can you tell a wheel is slipping from excessive force on the brakes or spinning from excessive accelerator travel (the problem sorted out by the ABS and ASR systems) or how can you tell a wheel is side-slipping from an excessive steering wheel angle for the available traction (the ESP problem). You could have a loss of traction in the direction of travel independently of a loss of traction sideways, or you could have both simultaneously. Then, with that first set of questions answered, you need the answer to one more: which axle’s wheels are sliding to the side? You need to know this to tell whether to engage the front outside or the rear inside brake to correct the slide.

Let’s turn to ABS/ASR for a start. Each of those systems relies mostly on the wheelspeed sensors’ signals to identify vehicle speed and, more importantly, on the rate of change of vehicle speed at each individual wheel. The control-unit computer includes in its read-only memory a maximum change of wheelspeed compatible with even the best possible traction. This rate of change is the engagement threshold for the ABS or ASR traction control measures.

No carmaker blurts that precise number out, because it cost so much time and money to discover and develop through multiple brake system experiments and redesigns. Nonetheless, here at StarTuned, we’re privately inclined to suspect the ABS/ASR acceleration/deceleration maximum threshold is roughly 1.5-1.6 G’s for most Mercedes-Benz models. If a wheel slows or accelerates more quickly than the G-force threshold, more quickly than is compatible with a rotation speed change under the best possible traction conditions, that wheel’s sliding or slipping, so the system applies its countermeasures. It’s interesting that the ESP lateral acceleration sensor has a maximum range of 1.4 G’s, and it’s reasonable to conjecture that’s because the engineers doubt such a lateral force will ever be exceeded without sideslip.

From the yaw sensor, the computer determines the direction and speed of the rotation of the vehicle around its vertical centerline, its rate of turn, in other words. As we’ll discuss next issue, the sensor generates a different voltage output for right turns compared to left turns even at the same rate, enabling the control unit to distinguish both the rate and direction of the turn from different magnitudes of the same information signal.

From the wheelspeed, the steering angle sensor and the yaw, the computer can calculate an expected lateral force, however. No doubt there’s a certain range to factor in more or less grippy tires, tilted roadways, high sidewinds and the like, but the computer can almost instantaneously determine a plausible value and compare that to the lateral acceleration sensor signal. That still doesn’t tell whether the wheels are sideslipping, however.

If the fronts slip, there’d be less yaw than predicted; if the rears slip, there’d be more. So we conjecture the real trigger for ESP activation comes from the lateral acceleration sensor. Probably not in the way you’d imagine, putting traction controls to work as the lateral acceleration reaches a threshold. Probably what the system does, instead, is to look for a sudden reduction in lateral force with no simultaneous change in wheelspeed or in steering wheel angle. You’ll recall the quibbles we had with the conceptual drawing at the beginning of this article, that the sideforce must have just declined from its maximum. That unexpected reduction of sideforce could only be the direct result of sideslip. That reduction says wheelslip has just begun, and the yaw sensor simultaneously flags the slipping axle: Less yaw means the fronts are breaking loose, more means the rears.

So now, the computer knows there’s slip and knows where. Next issue, we’ll see how it corrects the problem and regains traction, if it can.

StarTuned thanks the students and instructors at the Chicago Area Mercedes-Benz Elite Training School, part of UTI. Their knowledge, enthusiasm and cooperation were very helpful, and we hope to drop in on them again.

0 Comments