Gasoline ain’t what it used to be, and it’s only going to get worse. Here, Henry gives us an intro to a tuning topic that’s often overlooked, with more installments to follow.

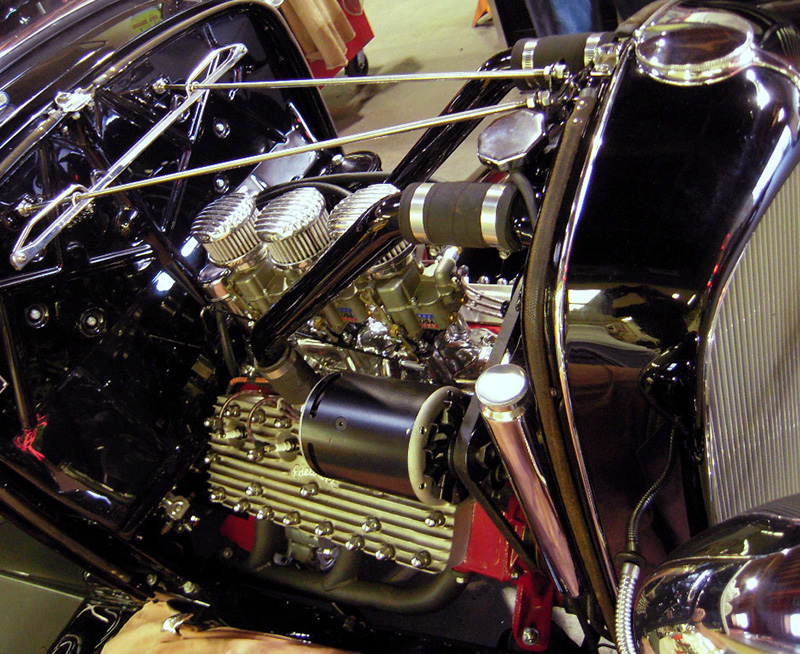

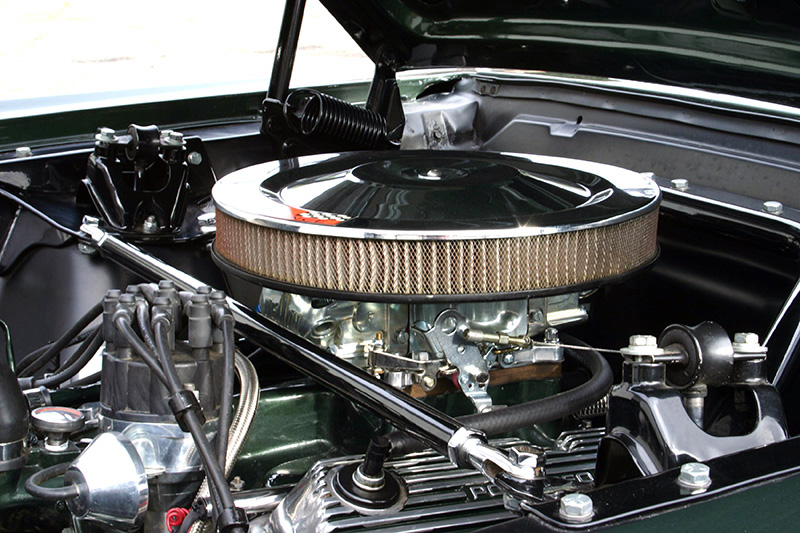

This flathead V8 is in Vic Edelbrock, Jr.’s personal 1932 Ford street rod. It’s equipped with three of Edelbrock’s new Model 94 carburetors, which have made it very driveable, reliable, and fun even on today’s gasoline.

Vintage cars, trucks, and hot rods are becoming more desirable and valuable as both transportation and investments. These vehicles were designed and tuned to run very well with the leaded gasoline that was in use when they were built, but many of them lack performance and driveability with today’s reformulated unleaded gasoline. Modern fuel-injected engines that are in the new cars of today have a computer that is continuously tuning the air/fuel mixture and ignition spark advance to adapt to changes in gasoline, air density, and engine load. Since a vintage carburetor-equipped engine can’t adjust itself for the changes in gasoline, there is a market for a hot rod professional who can make the necessary tuning adjustments for the owners of these vintage vehicles.

Neogas

Although the government touts the addition of ethanol to gasoline as a means of reducing both air pollution and our dependence on foreign oil, it can cause performance problems and deterioration of fuel system components, especially in older vehicles. Plus, ethanol hasn’t got near the energy density of gasoline, so both fuel efficiency and power output are diminished.

Gasoline has changed quite a bit since the 1970s, including the removal of lead and major alterations in formulation to reduce both the evaporative and exhaust emissions of an engine. The federal government has recently mandated the oxygenation of gasoline with ethanol in an effort to further reduce exhaust emissions and our dependence on foreign oil, but adding ethanol often causes driveability and reliability problems when it is used in a vintage vehicle that was not designed to tolerate it, and not tuned for it.

Reformulated gasoline with ethanol is actually quite different from the leaded gasoline that a vintage carburetor-equipped engine was designed and tuned to use. The main differences between today’s gasoline and the leaded fuel of days past are that the burn time is faster because of the removal of lead, and it is also not as easy for the spark plug to ignite the air/fuel charge as it was before the changes in formulation because they have reduced volatility to limit evaporative emissions. The current maximum ethanol content of pump gasoline is 10%, but it looks like new regulations will increase that to 15% or more in the future, which may lead to even more driveability problems with vintage carburetor-equipped engines and fuel injected vehicles built before about 2001.

A carbureted engine will most likely need to have its air/fuel mixture and ignition spark advance curves retuned for these new blends of reformulated gasoline. The addition of ethanol to the gasoline will cause the air/fuel mixture to shift leaner than the same gasoline without ethanol, which can cause a further loss in driveability and throttle response. A modern computer-controlled, fuel-injected vehicle should be okay with gasoline that contains up to 10% ethanol, but many modern fuel-injected vehicles built before 2001 may experience fuel system problems and driveability issues if the ethanol level exceeds 10%.

Choices

The supercharged 392 Hemi engine in this street rod is as reliable as it is powerful because both the ignition curve and the fuel mix have been tuned for modern gasoline.

There are several different options for making these vehicles both reliable and fun to drive. They vary from tuning the ignition spark advance and air/fuel mixtures of the original equipment engine package to replacing the powertrain with an engine package taken out of a newer vehicle, with a high-performance “crate” engine, or with one of the emissions-compliant E-Rod engine packages.

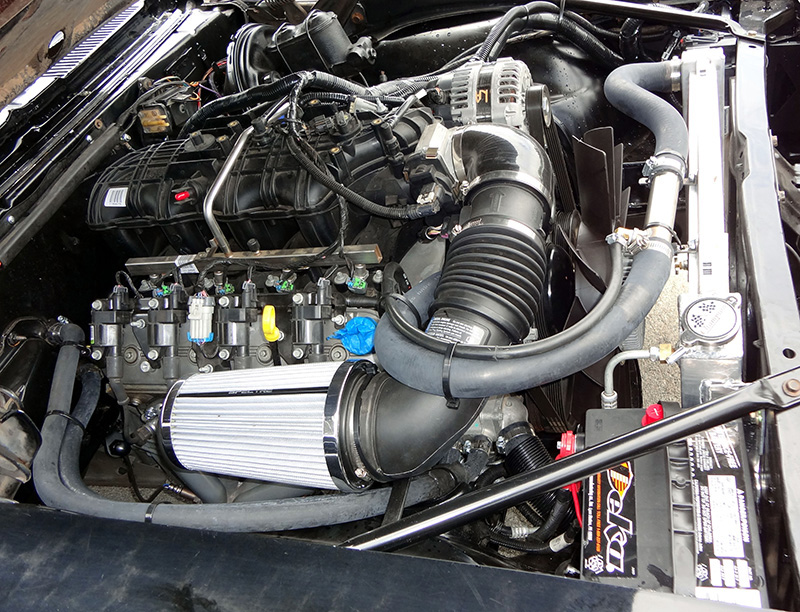

This 1967 Camaro has a modern fuel-injected engine under the hood. Transplants usually require some re-engineering, however.

If you choose to go with the engine swap, you’ll have to decide on some further options:Â Will you switch it to a carburetor, will you retain the O.E. computer-controlled fuel injection, or will you go with one of the many aftermarket fuel injection systems that are on the market?

The modern fuel-injected engine package pulled from a modern vehicle can work very well, but you and your customer should be aware that this option is not always as simple as it appears. The engineers who programmed the engine-management computer spent hundreds of hours tuning the program that controls the ignition spark advance and the air/fuel mixture mixtures for the vehicle it was going into on the assembly line. In contrast, the new E-ROD engine packages that General Motors offers were designed to be put into vintage vehicles.

Out of range

In the ’67 Camaro shown above, the intake is picking up hot air from right over an exhaust manifold. This caused both performance and driveability problems.

You would think that an engine swap with a newer fuel-injected engine package out of a late-model car and going into a vintage vehicle should be fairly simple, but that is not always the case. The problems begin when the input data is outside of what the computer was programmed to see. The problems can range from “minor†performance and driveability issues to those that are safety-related. One example of a safety-related issue would be with an engine package that uses an electronic throttle control. An installation or programming error could cause unintended acceleration and perhaps a collision.

This 1947 Suburban also has a modern fuel-injected engine, but the air box supplies cool outside air just as the engine management system likes it.

One of the problems we see the most often that will cause both performance and driveability issues is the location of the engine’s air intake. The factory engineers would have programmed the computer for the “cool†air that comes through a duct from outside the engine compartment. On the other hand, if the air is instead taken from inside the engine compartment the inlet air temperature can range from 150 to 300 deg. F. The computer will see these high air temperatures as a problem because it is much higher than it was programmed to expect, therefore it will most likely retard the ignition timing and lean down the air/fuel mixtures, which will cause the engine’s performance and driveability to suffer. In addition, it may set a trouble code and turn on the MIL (Malfunction Indicator Lamp, if you have included it in the swap).

Obviously, the O.E. engineers programmed the computer for a particular vehicle of a certain weight, with its own aerodynamic profile, and final drive ratio (overdrive transmission, tire diameter, and rear end gear ratio). This provides the engine with the baseline settings of what the spark timing and the air/fuel mixture should be, which are then electronically fine-tuned as the computer reads the inputs from an array of sensors. When you put such an engine package into a vintage vehicle, you can run into programming problems because those factors and others are going to be different.

Some of the most important inputs the computer looks at are intake air temperature, air density via the MAF, engine rpm and vacuum, throttle position, air/fuel mixture (oxygen or A/F ratio sensor), and coolant temperature. If these signals do not match up with what the computer was programmed to see, the engine will not perform as it should, and may even go into what’s commonly called “Limp Home Mode,” or “LOS” (Limited Operating Strategy).

Aftermarket Fuel Injection Systems

Aftermarket fuel injection systems can allow you to install something more modern and efficient than a carburetor on a vintage engine. Most of these systems are either self-tuning or programmable, but they require that the engine use a camshaft that is designed for feedback/closed-loop fuel injection so the oxygen sensors can accurately read and then adjust the air/fuel mixture. Also, remember that the inlet air temperatures must be in the range that the computer was programmed to expect. These systems do not come cheap, but if you are computer-savvy it is an option that is well worth considering.

Carburetion lives

The carburetor is still alive and well. There are quite a few new performance and reproduction vintage carburetors on the market, plus almost any original carburetor can be tuned for today’s gasoline. You can keep the engine looking just like it did when it was new with all the original parts, or update the performance and appearance with aftermarket parts such as the carburetor, distributor, and air cleaner to dress up the look of the engine. To many people, a vintage vehicle just does not look right when the hood is open unless there is a carburetor on the top of the engine.

The downside of the carbureted option is that since there is no on-board computer to perform the tuning changes that are needed for today’s ever-changing gasoline formulations, someone will need to tune the air/fuel mixture and ignition timing curves for the needs of the engine on the new fuel. The good news is this offers the experienced tuner with a challenge that, when properly performed, will make you a hero in the eyes of the vehicle’s owner.

Steps

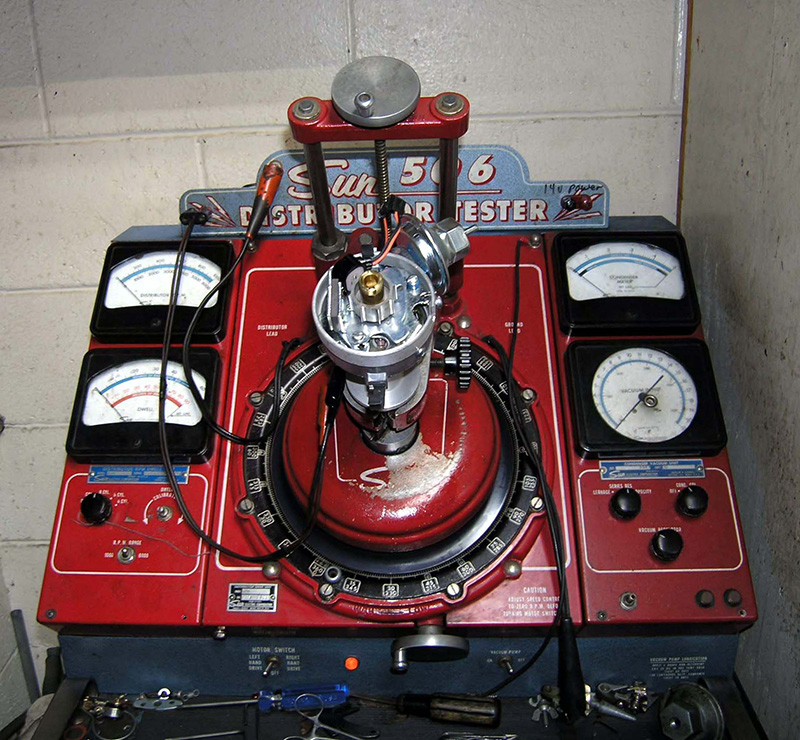

Reformulated gasoline burns faster, but is harder to ignite than old-fashioned fuel. So, the ignition timing must be adjusted accordingly.

The first step in tuning is to customize the base or initial ignition timing, then the mechanical/rpm-based advance curve and the vacuum-based advance systems for the needs of the engine with the blend of gasoline that will be used. The total mechanical timing a typical vintage engine needs for maximum efficiency has not changed by very much even with the newest blends, but the initial timing and the amount of additional timing from the vacuum advance has changed due to the removal of lead and other reformulation factors. This modern gasoline causes a typical vintage carburetor-equipped engine to respond favorably to more initial/base timing because the fuel is harder to ignite (it’s slightly less volatile — its Reid vapor pressure is lower). We set the initial timing of many engines at a point that would have had the engine fighting the starter when gas was gas, but if we set it back where we would have in the ’60s and ’70’s we’d get hesitation when we tried to rev it. On the other hand, the engine needs less spark advance from the vacuum system is because the fuel burns somewhat faster. During our tests with a five-gas exhaust analyzer, we found that if you use a stock vacuum advance the misfire rate is quite high, but if you limit the vacuum advance to 10 to 12 degrees (instead of the 18 to 24 degrees of days past), the misfire rate drops.

The next step is to check and tune the air/fuel mixtures that the engine will see during idle, cruise/low load, power and acceleration, and cold starting conditions. The way most “mechanics” determined if an engine’s air/fuel mixture was correct back in the 1960s and 1970s was to look at the color on the porcelain nose portion of the spark plugs. Today’s reformulated gasoline, however, does not leave any color on the spark plug unless the mix is extremely rich. The best way to “read†what air/fuel ratio carbureted engine has is to use a exhaust gas analyzer, or a wide-band oxygen sensor-based digital air/fuel meter.

Good starting points would be:

- 13.41-14.1:1 air/fuel ratio at idle

- 14.0-14.2:1 at cruise

- 12.0:1 during power/acceleration

- Some high-performance engines with fast-burn cylinder heads may need a leaner power/acceleration ratio of 13.2:1.

Swelling, rotting, and corroding

It is also important that you update the fuel system including the rubber fuel lines so they can withstand the corrosive effects of gasoline that contains ethanol. The ethanol portion of today’s gasoline can act as a solvent that will attack any fuel system component made with older plastic or rubber compounds. The combination of exposure of rubber and plastics to high heat conditions and today’s gasoline greatly accelerate swelling and deterioration problems.

Ethanol also readily attracts water from its surroundings (such as the moisture in the air in the fuel tank), and it takes as little as one tablespoon of water per gallon of to cause the ethanol to phase-separate from the gasoline. This extremely corrosive mixture of ethanol and water will drop to the bottom of the tank. Not only will it be harmful to the components in the system, it can also cause major drivability problems.

The under-hood temperature of many vehicles can easily reach over 300 deg. F. during a hot soak (after the engine is shut off). Even though reformulated gasoline is less volatile than what we had in the old days (lower reed pressure), we are seeing more vapor lock issues recently.  The high heat is obviously a factor, but there’s also the theory that this is ethanol-related.

When it comes to racing gasoline, it’s another whole story. According to one of our valued sources, a race fuel engineer, some of the newest blends of race gas have actually made more power than expected. We’ll cover this interesting situation in a future HRP article

Speaking of future coverage, in upcoming issues of Hot Rod Professional, we will provide you with more in-depth articles on subjects such as tuning ignition advance and air/fuel ratios, mixture reading technology, changes in gasoline formulation, and much more. So, stay tuned (pun intended)!

by Henry Olsen

Â

0 Comments