Many years ago I had the honor of meeting Zora Arkus-Duntov at a cocktail reception put on by Chevrolet Public Relations as an adjunct to the introduction of some new models. Most of us were dressed in suits and ties, but he had the California-casual thing down, and was wearing an expensive tan cashmere sweater.

I had just become an auto mag tech writer and editor, so it hadn’t been very long since I’d been working as a line techician (well, a mechanic back then) in a dealership. I didn’t know who this nice-looking gentleman of about 65 was, but we immediately started talking about the technical and technological aspects of automobiles, particularly engines, not the lightweight “buff-book” stuff some of the other journalists present were discussing. We were into our second drink and plate of boiled shrimp by the time I realized with whom I was having this interesting and amiable conversation. When I did, all I could think of to blurt out was, “I’ve installed your cams!” Of course, I’d also admired and coveted the cars of which he was considered the father: Corvettes. I only saw him a couple of times thereafter, but he was always the same smiling, soft-spoken man with the pleasant accent.

I’m sure many HOT ROD Professional readers are too young to have had much to do with Ford flathead V8s, so you might not know that one of the big drawbacks of its design (introduced in 1932!) was that the exhaust had to exit through passages in the water jacket, which put a big load on the cooling system (two water pumps, 24 quarts of coolant, and a huge radiator were needed) and limited volumetric efficiency. There was an ingenious cure for this, though: Ardun heads, which gave you OHV hemi efficiency and a completely different path for the spent gases of combustion. Properly set up, flatheads so equipped could top 300 hp, believe it or not.

These excellent aluminum heads came up recently in a discussion with our esteemed contributor Henry Olsen, who had a vintage street rod in his shop with just such an engine, and I decided to research them. Well, duh, the name Ardun comes from Arkus-Duntov, a fact I had either forgotten, or never knew in the first place.

That led me to look into Mr. Arkus-Duntov’s life. And quite an adventurous, interesting, and successful life it was, far more so than can be adequately described in a one-page editorial. So, I’ll just mention the salient points, if that’s not too disrespectful to the man’s memory.

Zora Arkus Duntov, 1909 – 1996

Born in Belgium on Christmas Day of 1909 to Russian parents (his father was a mining engineer, and his mother a medical student), Zora showed an enterprising streak while still a boy. There’s even a story about him smuggling gold from France into Belgium in the chassis of a Mercedes at 16. The family moved to Leningrad (inexplicably given the horrors of the Russian revolution), then to Berlin in 1927 (how did they get away from Stalin?), where Zora graduated from a top-tier engineering school in 1934. He also began racing motorcycles and cars, and wrote engineering papers for German automotive publications.

Zora’s family was Jewish, so it’s no surprise that when Nazi intentions toward that group became apparent that they moved to Paris, where he married a beautiful German girl, Elfi Wolff, who danced with the Folies Bergère (the marriage lasted 57 years until his death in 1996). About the same time, he joined the French air force and became a pilot.

When France surrendered, Zora somehow arranged for his whole family to escape to Portugal. According to the movie script-like Wikipedia description, “Elfi, who was still living in Paris at the time, made a dramatic dash to Bordeaux in her MG just ahead of the advancing Nazi troops.” She joined the rest of the family, and they sailed for New York.

Zora became a U.S. citizen, and with his brother Yura formed Ardun Mechanical in Manhattan for the manufacture of munitions, but it became much more famous for the cylinder heads mentioned above. The company eventually employed 300 people.

But he remained passionate about racing, and shortly after the war he twice tried to qualify his own Talbot-Lago car for the Indy 500. He didn’t succeed, but that’s a pretty stiff venue. Next, he went to England to help develop the Allard, a light sports car powered by either a Ford flathead, or a Cadillac V8, one of which he drove at the 1952 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

At a New York car show in 1953, he was dazzled by the looks of the just-introduced Chevrolet Corvette, only to be disappointed when he saw that it was powered by a “Blue-Flame” inline six — just a couple of minor steps up from the plebian “stove bolt” that had powered Chevy sedans and pickups since 1929. So, he wrote to GM president Ed Cole saying he would love the opportunity to help develop the car. Cole was impressed, and Zora started as a Chevrolet staff engineer shortly thereafter.

There’s no way I can do justice here to the corporate wrangling that went on between Arkus-Duntov and the big company’s top designers and upper management during the evolution of the Corvette. Suffice it to say that it was a battle between executives who believed that style was the key to selling cars, and Zora who believed in the substantive engineering that provided world-class performance. He stated his vision for Chevrolet’s future in a memo entitled, “Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet,” which helped transform the company’s philosophy from conservative to “Heartbeat of America” exciting.

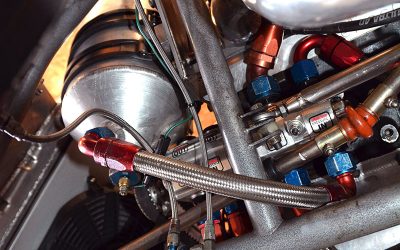

A few of Zora’s early ‘Vette accomplishments include the installation of the small-block 265 V8 in 1955, the winning of the Pikes Peak trophy and the setting of the 150 mph record for a production car at Daytona Beach in ’56, and the introduction of the Rochester mechanical fuel injection system, which he helped design, in ’57 (this made the magic “one horsepower per cubic inch” 283 legendary). Then came the first four-wheel discs on an American car, independent rear suspension, and many more innovations. Throughout all this, he found time to develop the famous Duntov high-lift cam that found its way into thousands of shade-tree hot rods.

In his obituary, famous columnist George Will wrote, “If you do not mourn his passing, you are not a good American.” His ashes are enshrined in the National Corvette Museum, Bowling Green, KY.

If you’d like to read more about the man who did so much to shape American automotive culture, there are several good biographies available, and hundreds of articles on the Internet.

0 Comments