You’ve pulled the code, identified the problem part, replaced it and sent the customer down the road in record time. Now he’s back with the MIL on again and he seems less than impressed with your rapid repair and more wondering what he paid to have it fixed. What do you do when the code keeps coming back and just won’t go away? Let’s look at some common mistakes and how to clear those codes for good.

If you’ve been driving cars in the last 20 years, you’re all too familiar with the MIL and the little gut check you feel when it pops on unexpectedly. What’s wrong? Is it serious? Am I going to make it home? How much is this going to cost? As a technician that gut check is amplified by a million times when that evil light comes on during your post repair test drive. (You are doing a post repair test drive, right?) This is a very good time to not panic, take a deep breath and focus.

There is always a reason the light comes on, and that can be solved. Sometimes a returning light is due to a misdiagnosis, sometimes it’s a completely separate issue, and sometimes it can be as simple as an incomplete repair procedure. Understanding why the light comes back on will help you understand what it will take to repair the vehicle and keep that MIL off.

The automatic self-checking system on any vehicle sold in the USA after 1996 is referred to as OBD II (short for OnBoard Diagnostics version II) and has certain aspects that are federally mandated in an effort to reduce noxious gases produced by our cars. It’s worth noting that is working! Love it or hate it, it’s made a big difference in our air quality and makes some bits of valuable diagnostic information readily available to any technician with a universal scanner.

The system monitors expected things like engine misfires and other problems that cause runnability problems, but it also monitors systems that seem to have little effect on drivability at all, like the EVAP and catalyst systems. When a fault is identified by the ECM it may, depending on the code, turn on the MIL right away or it may wait for it to fail again. Once the light is on it will typically stay on until the cause is repaired or the fault hasn’t recurred in a certain number of drive cycles or successful tests. Even though a universal OBD II code reader can give you the codes, freeze frame data (engine conditions at the time the code set) and can clear the codes, when it comes to actually diagnosing most problems in Nissan vehicles, the Consult III Plus is mandatory.

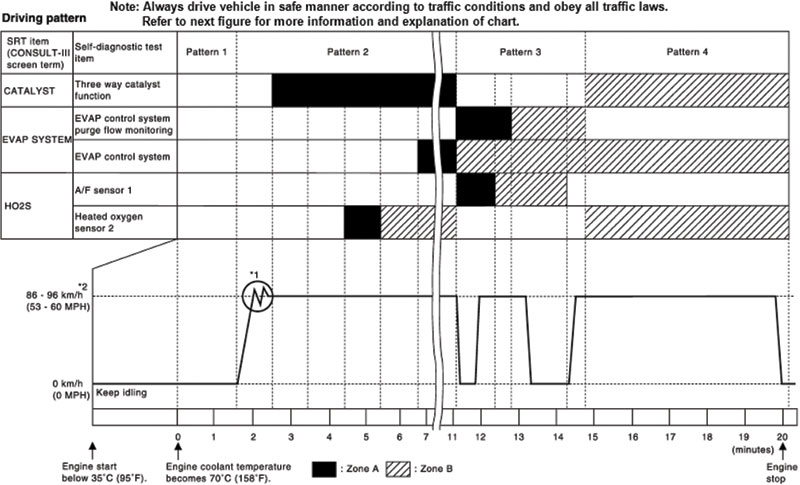

Part of the system that is mandated is the I/M monitors (Inspection and Maintenance) or SRT (System Readiness Tests). These are extensive self-check algorithms that confirm that the vehicle is operating properly. Rather than wait for something to go wrong, these programs actually test certain systems pre-emptively.

These tests are divided into two types — continuous and non-continuous monitors. Knowing which type of system you are trying to fix will help you to confirm that your repair was successful. Continuous monitors are, like the name implies, continuously active. These will typically make confirming your repair faster, as any faults usually return quickly. The most obvious example would be testing for cylinder misfires. The ECM is continually monitoring for misfires and doesn’t have to wait on other systems to test before it sets a code.

Non-continuous monitors require that certain conditions be met before the system is tested. A great example is the P0128 thermostat performance code. Obviously, this can only be tested as the engine is warming up. These can be much trickier as some of these “conditions†can be really involved and require multiple drive cycles to complete the test. In addition, some monitors won’t test if other codes are present.

A prime example might be a code stored for a failed oxygen sensor preventing the ECM from checking the catalyst. You end up fixing the oxygen sensor only to have the light come back on in 20 miles because the ECM finally tested the catalyst and found that it had failed. Another common stumbling point is that an EVAP leak test typically requires the fuel level to be between ¼ and ¾ tank as well as a cold soak engine start-up. You might find and fix an EVAP leak only to have the light come back on with another EVAP fault a week later when the conditions are finally met to run the EVAP monitor again.

With the deck seemingly stacked against you, how can you be confident in your repair, that the light is off for good? The proper diagnostic procedure is a good start. With almost every code and driveability issue Nissan recommends, in the service manual, a general diagnostic check should be performed at the very beginning of the diagnosis. In this process, confirming the customer complaint, checking and recording all stored DTCs, and checking TSBs must be done first. (It is worth noting that not all trouble codes will cause the MIL to come on.)

Recording DTCs, freeze frame data and even radio station presets is a smart move as well since many test procedures require that the battery be disconnected as part of the diagnosis and this valuable information might be lost, making your diagnosis that much harder. Checking TSBs early is invaluable to determine your issue have been addressed. With TSBs, Nissan engineers have taken the time to lay out a very detailed diagnosis and repair procedure that will most certainly get you to a complete repair in record time.

There is an unfortunate situation that has to be addressed when considering the root cause of a trouble code or symptom that doesn’t go away after the repair. More often than not it is a matter of a failure on the technician’s part. Most of the time the root cause is either something that was missed in the diagnosis, or that the repair wasn’t performed correctly. Automotive repair isn’t easy, and rushing the job is tempting when it seems like the whole shop is waiting on you.

A prime example is in the wire harness testing that makes up the majority of the component testing in the service manual. Resistance, ground, power, and short circuit testing are time consuming, especially if the ECM isn’t readily accessible. Failing to perform this testing might lead you to an incorrect diagnosis and replacing a part that isn’t bad, only to have the light come right back on as the SRT tries to clear. Besides harness testing there are also certain systems that need to be calibrated as part of the repair.

Take the example of the electronically controlled throttle body you might find in a 2005 Nissan Maxima. If the throttle body actuator starts to fail and have difficulty controlling the engine speed, it will set a code P0507, “Idle control system RPM higher than expected,†accompanied by an obviously high idle. A technician in a hurry has many ways to fail at this repair if he skips diagnostic steps.

After making sure the throttle body is clean, the connector isn’t damaged, and vacuum leaks have been repaired, it’s tempting to simply throw in the towel and condemn the throttle body. The diagnostic procedure includes testing the wire harness between the ECM and throttle body, performing the cam/crank re-learn procedure, and performing the idle air volume learn procedure. A technician cutting corners could inadvertently install a very expensive throttle body that simply isn’t necessary. The procedure has many steps and can be daunting. It’s a good idea to print it off and take it with you to the car, then you can simply check off the steps as you complete them.

Just one possible scenario, for this Maxima in question, might go something like this; the code P0507 is present and the idle is surging. The technician finds the throttle body dirty and a vacuum hose leaking. Repairing the two issues and clearing the code he finds the idle is still misbehaving and the code comes back. Seeing no other obvious faults, he replaces the throttle body and the engine still isn’t idling right. Then, reading the procedure as a last resort, he runs the cam/crank re-learn procedure and the idle air volume re-learn; the engine responds and is now running perfectly.

It sounds like a good fix. Little did the technician know, the replacement of the throttle body had little to do with the actual fix. After repairing the vacuum leak and the folded air intake tube when he cleaned the throttle body, the actual fault was fixed. All that was needed at that point was running the re-learn procedures. A quick count shows as many as four test drives were performed in this scenario, and the extra cost to the customer and time spent was unnecessary.

One common mistake that is surprisingly easy to make is the case of mistaken identity. Let’s say you’ve got a Frontier with the 3.3L V-6 and it’s got an oxygen sensor code (P0132, P0138 etc.). Being diligent, you start with a quick visual inspection of the engine and find an oxygen sensor with solderless butt connectors a few inches from the connector on the top of the engine. Too easy! You replace the oxygen sensor clear the codes, run the engine, and confirm no codes come back. Then the next day the customer returns with the MIL on again and the same code stored.

In this scenario the spliced oxygen sensor was most certainly not an OE part as many aftermarket oxygen sensors will be listed as universal. The installer simply splices the old connector onto the new sensor and away you go. This is far from ideal and can easily lead to problems with corrosion in the connectors or simply a cheap aftermarket part that doesn’t perform like a genuine Nissan part.

These poor connections don’t necessarily mean the part doesn’t work. An intermittent failure on the sensor for the opposite bank could be the real culprit. Taking a short cut and not testing the part for the actual failure can be an embarrassing mistake, even more so if you change the part on the wrong bank. On many Nissan engines, testing the oxygen sensors is very easy as the connectors are frequently located right on top of the engine. Even if you don’t have a graphing multimeter to test the sensor output, you can easily disconnect the sensor with the data stream up on the scanner to confirm you’ve got the right sensor.

Diagnostic errors will frequently lead to codes that just won’t go away. Simple mistakes during the repair can lead to comebacks just as easily. Following procedure is more important than making good time on the job. Taking the time to use a torque wrench during throttle body or intake manifold replacements can save you from having a P0171/P0174 lean condition code popping up. For that matter all it takes is a simple gasket slipping out of place, a missing vacuum hose, or failing to remove all the old gasket material to cause the same lean condition you were trying to fix.

As soon as the engine is running, check the long-term and short-term fuel trims. Anything over about 15 in the long-term fuel trim will typically set the lean code. The fun exception is immediately after a successful repair, where the long-term fuel trim will remain high (from the failure you repaired) and the short-term fuel trim will be just as high with a negative number to compensate in the other direction, as the ECM slowly brings the long-term fuel trim down to its new proper level. Sometimes good enough isn’t good enough. Even if the lean codes don’t come back, if your fuel trims remain above 8 or so you still have a “lean†problem. If it’s over 10, you can fully expect the codes to come back sooner or later as driving conditions change the engine’s fuel needs.

A good practice with any kind of repair, from engine replacements to oil changes, is to take a minute and look over your repair one last time. Examine the bolts. Do you remember torquing each one? Look for loose connectors, vacuum hoses, wire hold down devices, taut wires, or errant fluids. Depending on the work performed, a great time to do this is when the engine is warming up. With so many crisscrossing wires, hoses, and cables, it’s easy to have too much tension pulling on a connector if the harnesses aren’t routed correctly. In some cases, you might even end up with connectors plugged into the wrong sensors.

A prime example is the input and output speed sensors on the Nissan RE5F22A 5-speed automatic transmission. Two identical connectors fit two separate sensors that provide different information to the ECM. With the harness installed and routed correctly, crossing these wires is unlikely and it is quite the stretch, but in some cases, if the harness isn’t routed correctly, the wires can be connected to the wrong sensors causing codes that simply won’t go away.

Unfortunately, it’s not possible for the diagnostic procedure in the service manual to address each and every possible pitfall that can cause returning codes. Keeping an open mind and truly understanding how the systems work will eventually be necessary. Finding the cause of a code doesn’t preclude the possibility that there is a cause of the cause of the code.

For example, lets look at pretty much any Nissan model after the year 2000, as just about every engine now uses coil on plug ignition (with the exception of some trucks with the 3.3L). Say you diagnose an engine misfire code (P0301, P0302 etc.) as a faulty coil. You replace the coil and send the customer on his way in record time only to have him come back a week later with another misfire code. Repeat the diagnostic procedure and replace another failed coil, and again, and again. Are all the coils simply old and failing or is something else causing it?

OE ignition coils have no moving parts and, when used properly, should outlast the engine. Check the spark plug gap. An excessive gap in the spark plug (from normal wear, faulty installation, damaged electrode, etc.) can put extra strain on the coils and cause them to burn out prematurely. Another example might be oxygen sensor heaters. If a heater is shorted out in the sensor it’s easy to test and find the faulty sensor and replace it, only to have the code come right back. Just because the sensor tests bad doesn’t mean the rest of the system is good, especially considering that a shorted sensor can easily burn the fuse in the IPDM.

You may not win them all but being diligent, testing your repairs, checking your work and completing those SRTs will certainly help keep those comeback MILs away. When you do find a persistent code, don’t take it personally. Breathe deep, keep your mind open and you’ll find your answer. In the end, fewer comebacks make you a better technician than just beating flat rate.

Download PDF

0 Comments